1909

Recollections of sixty years

|

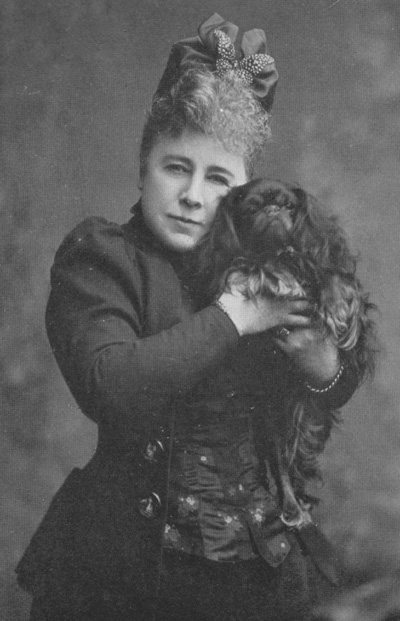

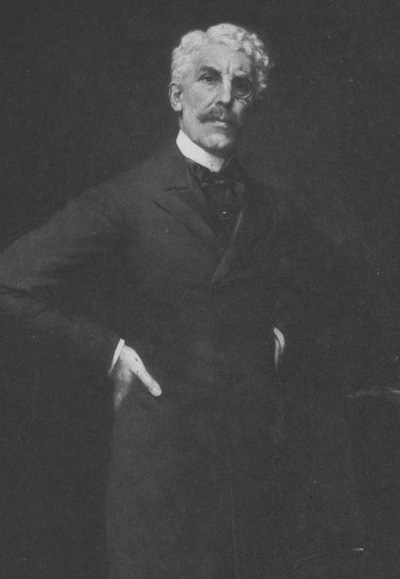

| In 1909 Sir Squire and Lady Marie Bancroft (he was knighted in 1897) decided on "re-telling in a different way, and with that greater freedom which is born of the lapse of time, things which happened" and put "within a single book the whole of our memories of sixty years." Some of the stories here repeat almost word for word those in the 1888 book Mr. and Mrs. Bancroft. But in rewriting the parts concerning Wilkie they have added the story about his opium addiction and one new letter. The long narrative about the production of Man and Wife is reproduced here in full. The book also contains many portraits and illustrations, mainly of the authors. |

12, Grosvenor Square,

May 10, 1872.

Money has been placed on your stage. But I feel that I ought to thank you, 1n

words not addressed through another, for the gratification afforded me. Had the

play been written by a stranger to me, I should have enjoyed extremely such

excellent acting -an enjoyment necessarily heightened to an author whose

conceptions the acting embodied and adorned. Truly and obliged,

LYTTON.

To MRS. BANCROFT.

The Frederick Lehmanns—for many years the kindest of friends, for some of

them dear neighbours—who were of the party in the author’s box, soon afterwards

included us in a charming dinner-party, when the guests invited included Lord

Lytton, Lord Chief Justice Cockburn, and Wilkie Collins. It was at that time we

first saw the then freshly painted portrait of their daughter Nina (now Lady

Campbell), a picture of lovely childhood which alone would have immortalised the

brush of Millais.

[p131]

…

As we have shown, our production of The School for Scandal attracted remarkable notice and proved a success of the first rank artistically and financially, aided greatly in the latter field by the bold step then taken, and explained in an earlier chapter, of increasing the price of seats.

We will quote one or two extracts, equally characteristic and appreciative, from a number of interesting letters we received at the time. Wilkie Collins wrote that the get-up of the comedy was simply wonderful; he had never before seen anything, within the space, so beautiful and so complete; but the splendid costumes and scenery did not live in his memory as did the acting of Mrs. Bancroft. He did not know when he had seen anything so fine as her playing of the great scene with Joseph; the truth and beauty of it, the marvellous play of expression in her face, the quiet and beautiful dignity of her repentance, were beyond all praise.

"I cannot tell you or tell her how it delighted and affected me. You, too, played admirably." The "key" of my performance he thought perhaps a little too low; but the conception of the man’s character he considered most excellent. "I left my seat in a red-hot fever of enthusiasm. I have all sorts of things to say about the acting—which cannot be said here—when we next meet."

[p141]

…

Soon after Robertson’s death, having waded through reams of rubbish, we were told by Hare that Wilkie Collins, with whom he was acquainted, had written a drama founded on Man and Wife, a novel of Collins’s, which created a great stir at the time of its appearance. We read the play and at once agreed to produce it. A letter from the author, which we quote, ratifies the time we came to this decision, although the play was not acted until eighteen months later.

August 1, 1871.

So commenced a friendship which it was our privilege to enjoy through the remaining years of one whose masterly romances had lightened many an hour and given us infinite delight; for deep is our debt of gratitude to the creator of Margaret Vanstone, Mercy Merrick, Rachel Verrinder, Hester Dethridge, Captain Wragge, and Count Fosco. Wilkie Collins as a novelist might be compared with Sardou as a dramatist: the smallest brick in the structure is intentionally placed, and carries many others; if a single one were knocked out or displaced, serious results would to a certainty befall the entire fabric.

We asked Wilkie Collins to read his long-postponed play to the company. This he did with great effect and nervous force, giving all concerned a clear insight into his view of the characters; and, indeed, acting the old Scotch waiter with rare ability to roars of laughter. He had been, it should be recalled, a valued member of the band of amateurs led by Charles Dickens. We felt the play required certain alteration which could best be made after some rehearsals, and also were impressed with the necessity to do all that was possible to deserve a success in our first really new piece since the Robertson comedies; so we decided to aid the cast to the utmost of our power by taking small parts, my wife agreeing to play Blanche Lundie, a bright, pretty part, but quite of a secondary order, as was that she had just played in Money, while I offered to appear as the Doctor, an important but minor character confined to a dozen sentences.

A distinguished critic, in reviewing the progress of the stage during our management, went so far as to say that the greater portion of my wife’s career had been occupied in loyally subordinating herself for the sake of the general harmony of the work; while as for me, though myself an actor, I had shown the solid judgment of a man who is always ready to seek the co-operation of another histrion, apart from envy or malice. If my wife had been mindful of the obligations of art, and brought to her aid some of the fairest, brightest, and most refined actresses of her time, I had demonstrated the same impartiality in relation to my own sex; and our management had been conspicuous by the absence of that jealousy which too often dwarfed the character of a company in relation to its chiefs.

It is true that we never allowed considerations as to what parts there were for ourselves to bias our judgment in the acceptance or refusal of plays, as many instances recorded in this book will show.

We bestowed great pains upon the rehearsals of Collins’s play, often having the advantage of the author’s presence and assistance, which, when the work was well advanced, proved of real service. He also, in the kindest way, fell in with our views and altered the second act—in which he originally intended to divide the stage into two rooms, the parlour of the inn at Craig Fernie, and the adjoining pantry of old Bishopriggs—in accordance with our suggestions, and greatly, as he generously admitted, to the advantage of its representation. In this scene we went to unusual pains to realise a storm, and I think electric lightning was then first used, as was also an effect we introduced of moving clouds.

I was modest and nervous about stage-management in those days, and had not yet asserted myself in that capacity. Some of my views bore fruit in secret at Collins’s house, and one prominent member of the cast was schooled by me in his part at our own.

Man and Wife was produced in February 1873, in the presence of the most brilliant audience which the theatre had as yet seen assembled within its limited walls. The list included names well known throughout England in every art and calling; but, alas! it would now be but a sad record

"Our little life

Is rounded with a sleep."

We learned from one newspaper report of the première that the demand for places was so unprecedented that stalls were sent up to five guineas cash by speculators, while two guineas were offered for seats in other parts of the house. Literary and artistic London was present in unusual force, and an audience more representative of the intellect of the time has seldom been gathered within the walls of a theatre.

The great excitement might perhaps be ascribed to two causes. In the first place, Man and Wife was the first new play that had been produced at the Prince of Wales’s for some years; and in the second place, it was widely guessed that in this play the style of comedy with which our theatre was closely identified was to be in parts exchanged for drama of a more serious interest.

The cast also included Hare, Coghlan, Dewar, Mrs. Leigh Murray, and Lydia Foote, and the play was an instantaneous success.

Wilkie Collins passed almost all the evening in my dressing-room in a state of nervous terror painful to see, and which I could not have endured but for the short part I had to play. His sufferings were, however, lessened now and then by loud bursts of applause, which, fortunately, were just within earshot. Only for one brief moment did he see the stage that night, until he was summoned by the enthusiastic audience to receive their plaudits at the end of the play. Ever modest, ever generous, he largely attributed his success to the acting, and was loud in his admiration, at the final rehearsals, especially of Coghlan and Hare, Miss Foote and Mrs. Bancroft. He wrote to a friend describing the scene as follows

"It was certainly an extraordinary success. The pit got on its legs and cheered with all its might the moment I showed myself in front of the curtain. I counted that I had only thirty friends in the house to match against a picked band of the ‘ lower orders’ of literature and the drama assembled at the back of the dress circle to hiss and laugh at the first chance. The services of my friends were not required. The public never gave the ‘opposition’ a chance all through the evening. The acting, I hear all round, was superb; the Bancrofts, Lydia Foote, Hare, Coghlan, surpassed themselves; not a mistake made by anybody. The play was over at a quarter past eleven. It remains to be seen whether I can fill the theatre with a new audience. Thus far, the results have been extraordinary."

It is true that the opinion of the press critics was sharply divided, some attacking the play as ardently as others commended it; and some little disagreement reigned even over the acting of the three principal characters—Coghlan’s version of the brutal athlete, Geoffrey Delamayn, Dewar’s of the old Scotch waiter, and (strangely enough) Hare’s of the retired Scotch lawyer, Sir Patrick Lundie, all of which seemed to ourselves to be admirably rendered. All were agreed, however, that "one thing may at least be said, and that is, that the Prince of Wales’s company has shown itself capable of power." Small as was the part played by my wife, her performance was declared to be "simply exquisite in the charming piquancy of its mingled amiability, innocence, and droll shrewdness in the early portions of the play, and the naturally and quietly expressed pathos of the last act"; while as for my own little part of Doctor Speedwell, I found in it two causes of consolation, if any consolation were needed. One was the generous recognition it received.

"For this trifling part," it was written, "Mr. Bancroft assumes the most complete disguise, and entirely sinks his own identity with the skill as well as the generous abnegation of a thorough artist. The brows of the doctor, overshadowed by grey hair, the penetrating eyes that would cause a patient to hope or shudder as they formed a rapid diagnosis of his condition, were so unlike those of Bancroft that he was not for some time recognised."

The other cause of consolation was that the brevity of the part gave me frequent opportunities of seeing Aimée Desclée at the Princess’s Theatre, which was close by, in the early acts of Frou-Frou and others of her great parts. The impression left on my memory is that she was one of the finest and most touching actresses who ever adorned the art I love Did not Alexandre Dumas fils exclaim after her sadly early death?—"Elle nous a émus, et elle en est morte. Voilà tout son histoire!"

A tour of Man and Wife to the leading provincial theatres was soon started, Charles Wyndham being engaged for the part of Geoffrey Delamayn, and Ada Dyas for that of Anne Sylvester, both of whom acted with great éclat.

Man and Wife was a favourite play with the Royal Family: the then Prince of Wales saw it twice, and the Princess three times, between February 25 and March 4, and again were present before its withdrawal in July, being then accompanied by the Czarevitch and Czarevna, afterwards Emperor and Empress of Russia.

The favour thus shown to this production on one occasion caused, indirectly, the plot of a little domestic drama.

The Royal box was made by throwing two ordinary private boxes into one, and on a certain Friday night news reached the theatre that it was required for the following evening. Both boxes had been taken-one at the theatre, the other at a librarian’s in Bond Street-and nothing remained unlet but a small box on the top tier. Not to disappoint the Prince of Wales, it was decided that every effort should be made in the morning to arrange matters. The box which had been sold at’ the theatre was kindly given up by the purchaser, and a visit to Bond Street fortunately disclosed the name of the possessor of the other. The gentleman was a stockbroker, so a messenger was at once sent to his office in the city, only to find that he had just left. After a great deal of difficulty our invincible messenger succeeded in learning his private address, where, on arrival, he was told by the servant that "Master went to Liverpool on business this morning, and won’t be back till Monday."

The door of a room leading from the hall was opened at this moment, and a portly lady appeared upon the scene.

"Went to Liverpool!" echoed the messenger. "Nonsense! He’s going to the Prince of Wales’s Theatre this evening."

The portly lady now approached, and asked if she could be of any service. The messenger repeated his story and stated his errand. The lady smiled blandly, and said that, if the small box on the upper tier were reserved, matters no doubt would be amicably arranged in the evening, and so the man went away rejoicing.

At night, not long before the play began, the gentleman who had in vain been sought so urgently arrived in high spirits, accompanied by a very handsome lady. When the circumstances were explained to him, he very kindly agreed to put up with the alteration.

There ended our share in the transaction; but hardly were the unfortunate man and his attractive companion left alone than the portly lady from his private residence reached the theatre and asked to be shown to Box X. She was at once conducted there; the door was opened. Tableau! What explanation was given as to the business trip to Liverpool we never knew, or whether the third act of this domestic drama was rehearsed later at the Law Courts before "the President."

Although Man and Wife did not achieve the same length of run as some of its predecessors, the receipts for the first eighty performances were on a par with previous successes. Subsequently a summer of unusual heat affected the theatres, and the fêtes of many kinds given that year in honour of the Shah of Persia were also detrimental to them. Having broken the spell, as it were, and proved that we could be successful in plays widely different from those which first made the reputation of our management, we wrote to Wilkie Collins to say that his play would exhaust its attraction by the end of the season. This was his answer to the letter

90, GLOUCESTER PLACE

,When the season closed at the beginning of August, his play had been acted one hundred and thirty-six times.

I was travelling once to the Engadine in the pleasant companionship of the late Frederick Lehmann. We halted for the night at Coire, where the railway ended in those days, the rest of the journey consisting of a long and beautiful drive over the Albula or the Julier Pass. Lehmann, after we had dined, told me, very impressively, how the quaint old town reminded him of an eventful evening he had spent there on the homeward journey some years before with Wilkie Collins. Collins had then become a confirmed opium taker. They were close friends, and had passed some weeks together at St. Moritz. On the morning of their departure, as their carriage was creeping up the mountain road, Collins said to Lehmann, "Fred, I am in a terrible trouble. I have only just discovered that my laudanum has come to an end. I know, however, that there are six chemists at Coire; and if you and I pretend, separately, to be physicians, and each . chemist consents to give to each of us the maximum of opium he may by Swiss law, which is very strict, give to one person, I shall just have enough to get through the night. Afterwards we must go through the same thing at Basle. If we fail—Heaven help me! "The two friends played their parts skilfully, and, owing greatly to Lehmann’s perfect knowledge of the German language, they both succeeded, and the trying situation was saved.

In confirmation of this story I may add that one Sunday evening when our friends Sir William Fergusson, the eminent surgeon, and Mr. Critchett, the distinguished oculist and father of a distinguished son, Sir Anderson Critchett, were, with Wilkie Collies, among our guests, Critchett said to Sir William during dinner that he had Mr. Collins’s permission to ask him a question, which was this. The novelist had confided to him the quantity, which he named, of laudanum which he swallowed every night on going to bed, and which Critchett had told him was more than sufficient to prevent any ordinary person from ever awaking. He now asked Sir William if that was not well within the truth. Fergusson replied that the dose of opium to which Wilkie Collins from long usage had accustomed himself was enough to kill every man seated at the table.

It was during our performance of Man and Wife, I remember, that the death of Macready occurred.

…

It was he who, during his management of Drury Lane Theatre, was the pioneer of gorgeous Shakespearian productions. These were followed by the sumptuous revivals of Kean at the Princess’s, to be outdone in splendour by Irving at the Lyceum, of Dora in Paris, their critic had expressed a doubt whether adequate interpreters could be found in London for the great scene between the three men. The writer admitted at once that he was delighted to find this misgiving need not have been entertained. The scene, which unquestionably was the one upon which the play depended, was played as admirably in London as it had been at the Vaudeville in Paris. My performance in the scene as Count Orloff was held to give "a fresh proof of a fine power of impersonation, a thing somewhat different from acting in the loose sense which was too commonly attached to the word." The character demanded an unusual capacity for indicating rather than expressing a passionate emotion, and with my rendering of it the critic added that he could find no fault.

Equally welcome was the valued criticism of our ever-sympathetic friend

Wilkie Collins, who wrote that he had never seen me do anything on the stage in

such a thoroughly masterly manner as the performance of my share in the great

scene. "Your Triplet was an admirable piece of acting, most pathetic and true,

but the Russian (a far more difficult part to play) has beaten the Triplet."

[pp166-175]

…

In considering our decision [to retire], the fact must not be lost sight of that we started management at a time of life very exceptional for the taking on of serious responsibility. Besides, for our wants, and for the claims upon us, we now had all we needed. Great wealth, I fancy, must mean considerable anxiety I often think of words I heard spoken by a well-known man of vast riches when asked if he could mention what particular advantages he derived from the possession: "Only one comes to my mind," he replied—"I can afford to be robbed."

When we were quite resolved, we wrote to our near friends, and to those whom we thought sufficiently interested in such a matter. From the many replies we received, perhaps the following extracts will not be without interest, even after so long a lapse of time. Burnand wrote

DEAR B,

You are a lucky man, and a wise one. A deservedly fortunate pair, and a

sagacious couple.

At your age to be able to retire!! My! Wouldn’t I if I could! But I shall

never be able to retire; never free, never out of harness, until I lie down in

the loose-box and am carried off to the knackers, unless I go to the dogs

previously by some shorter and cheaper route.

Yours ever,

F. C. B.

In spite of severe illness these sympathetic lines were penned by Wilkie

Collins: "With all my heart I congratulate you both on retirement from the toils

and cares of a career of management which will be remembered among the noblest

traditions of the English stage."

[p258]

…

One of the leading Victorian novelists, WILKIE COLLINS, was long beloved by us. To what has already appeared about him in this volume I will add another of his letters.

90, GLOUCESTER PLACE

,Among some scraps and letters marked "Wilkie Collins" I found the following story. Whether he told it to me or whether I meant to tell it to him, I cannot recollect.

A tired woman walking alone on a dusty road in France hailed an advancing

diligence for a lift on her lonely way. She was allowed to get up on to the roof

of the coach, and she soon fell into a deep sleep. At the next stage, where

there was a change of horses, the guard and coachman forgot to tell the men who

replaced them about their extra passenger, who still slept heavily. Soon after a

fresh start had been made, there was an accident to the "skid," a very heavy

iron sabot. It was taken off the wheel and thrown up on to the roof. This

incident was followed, at the next stage, by the sight of blood running down the

panels of the diligence-and general consternation at finding the woman with her

head smashed in, and dead. Preparations for burial revealed the body to be not

that of a woman at all, but of a man. Further search disclosed letters which

proved him to be one of a desperate band of thieves, together with carefully

drawn up plans for robbing a neighbouring château, where he was going in

the disguise of a new housemaid.

[pp396-397]

From The Bancrofts – Recollections of Sixty Years London 1909