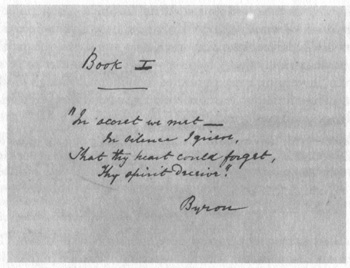

Book I

"In secret we met—

In silence I grieve,

That thy heart could forget,

Thy spirit deceive."

Byron

IOLÁNI by WILKIE COLLINS

This text was edited and prepared from the original manuscript by Professor Ira B. Nadel. His notes and editorial policy are also available here. The book was e-texted by James Rusk and prepared for web publication by Paul Lewis.

Introduction to Ioláni by Ira B. Nadel

Note on text and manuscript by Ira B. Nadel

Background on Ioláni by Paul Lewis

'The Captain's Last Love' a story thought to be based on some ideas from Ioláni

Ioláni;

or,

Tahiti as it was.

A

Romance

|

Book I

"In secret we met— |

|

Chapter I

Ioláni and Idía.

*It may be necessary, perhaps, at the outset of our narrative, to inform the reader that the vowels of the Polynesian language are sounded in the same manner as in the Italian. Thus, the proper names at the head of the present chapter should be pronounced as if written—Eolahne and Edeah.*

The last days of summer were near at hand, as one night, (while Tahíti was yet undiscovered by the voyagers of the North), the desolation of the great lake Vahíria was brightened by the presence of two human beings—a man and woman who were listlessly wandering along its rugged and deserted shores.

It was a strange and, to most hearts, an unalluring place. Looking forward from the spot occupied on this particular occasion by the woman and her companion, the eye encountered a long and almost unbroken range of mountains, whose jagged sides, though occasionally checquered by a clump of dwarf trees, or a patch of parched, scanty verdure, were for the most part bare and precipitous in the extreme. The different masses that formed the chain, were generally but little distinguishable, the one from the other, either in form or elevation, but were relived from absolute sameness, by the presence of the immense Orohéna (the loftiest mountain in the island) that farther in the distance, rose like a beacon over the tops of the inferior ranges. Lower, between the mountains and the lake, stretched large, dense tracts of forest land; and beneath these again, lay in the utterest confusion, mass upon mass of basalt rock, wild and jagged in form and reaching down almost to the water side; while, the waves of the Lake, but partially lightened by the rays of the young moon and preserved at most points from the wind by their natural guardians of forest and rock, looked wildest and gloomier than all beside, as they stretched forth dull and stagnant — were utterly lost in darkness, there faintly gleaming in the pale and fitful light. Truly, it was a desert and fearful spot. Hardly could the mind imagine from the appearance of those barren mountains, that their farther sides overlooked every variety that Nature could bestow—every charm that the seasons could dispense, and the blessed sunlight watch over and adorn.

Not a human habitation was to be seen on the borders of Vahíria. The natives generally, had a dread of the place and shunned it with the utmost perseverance. Their strange superstition has stored it for them, long since, with the spirit of the dead and the demons of a bloodshed and crime. Here, also, had been occasionally seen those wretched outcasts of humanity—the wild men, who haunted the loneliest fastnesses, at that period, of the mountains of Tahíti. These unfortunates, whose former existence in the Pacific Islands is well known even to the European traveller, were either confirmed and dangerous madmen, or victims marked by the relentless Priesthood of the land, for human sacrifices, who had escaped a horrible and often undeserved death, by embracing the melancholy alternative of perpetual exile from their land.

Of the two wanderers in this solitary spot, the woman was, in appearance, the most impressive and uncommon. Her face, thoroughly southern in its dusky, monotonous hue, and its soft, intelligent expression, possessed the additional attraction of an almost European regularity and refinement of feature. Her figure was taller and more slender than the general order of female forms among the population of the Islands, and was set off to the utmost advantage, by the simple and yet luxurious dress in which she was habited. No envious apparel concealed the delicate rounding of her shoulder, or the soft, regular heaving of the bosom below. The forepart of the sort of double shawl worn by the Polynesian woman, she had cast over her shoulder, so that it fell gracefully back upon the long, white tunic that hung beneath, while her beautiful and deep black hair, partially gathered up by a chaplet of flowers, streamed over all, in exquisite contrast with the snowy whiteness of her habiliment. Of her companion, it may be sufficient to say, that his appearance was chiefly remarkable from his great stature and from a commanding and dignified expression of countenance.

The connection existing between these two individuals, though considered as a serious moral infraction of the laws of society, in civilized countries, excited, among the luxurious people of the Pacific Island, neither indignation, nor contempt. Saving in a few instances of extreme and extraordinary attachment, Marriage was considered by the greater portion of the inhabitants, either, as a tie to be broken and reorganized at will, as a ceremonious pander to the fleeting passion of the hour, or, as a privilege so circumscribed by the pride of rank and possessions, as to oppose every obstacle to the few desirous of using it aright.

In the present instance, on the woman's side, unhallowed love was the simple and necessary consequence of the proud position of her companion among his people; for it was no other than Ioláni, Priest of Oro[,] the War-god, and brother of the King, whom the lowly-born Idía had won to the desert solitudes around the shores of the Lake.

Cunning, was the great principle of this man's life. It had supplied him with the means of securing every variety of iniquitous triumph, without a chance of failure or detection. In no character could more vile and dangerous elements be more secretly and securely lodged than in his. His natural malignity of disposition, was shielded by the most indomitable patience and contrivance. His cruelty, was refined by invention and aided by caution; and his fiery passions, were concealed by the most consummate hypocrisy and set off by the most ensnaring eloquence of speech and demeanour. The peculiar charms of Idía, caught at first sight, his sensual fancy, and he won her affections, as he had won the affections of all others before her, in security and triumph.

His last—perhaps for the time—his best beloved, was a woman, whose strong and many affections, destined her to a troubled existence either of turbulent joy or of overwhelming sorrow. Unlike the generality of her sex in the Pacific Islands, her emotions ran invariably into extremes, and the delusive impulse of the moment, decided her as dangerously as invariably, in every action of her life. From the moment when she had given her love, freely, truly and unsuspiciously, to the deceitful Priest, every thought of her heart was unconsciously dedicated to him alone. She looked at him, not as what he was, but as what he should be. To her, he was all in all—the one, bright perfection, that it was a delight to gaze upon and love. For, while it is the doubtful superiority of the mind, in much, to behold but an insufficiency; it is the humbler and happier faculty of the heart, in a little, to acknowledge an abundance.

And so she wandered on with him, through the solemn hours of that beautiful night, careless of the dangers with which superstition had stored the place, while her beloved was by her side, and revelling in her busy season of happiness, as securely as if misery had fled the habitations of earth, and quite had departed for ever from the human heart!

Chapter II

Aimáta and Home

It is summer and early morning. The young sun, whose rays, scarcely frustrate as

yet, the solemn darkness of the groves and forests, shows beautiful and bright,

on the meadowlands at the mountains['] feet. The sea-breeze has just arisen and

hies it hither and thither, among the inland adornments of the Islands of the

South. It refreshes the fruits, it awakens the flowers. It carries with it its

own fitful and delicate music, in the patterning of the falling dewdrops, as it

shakes them merrily from their topmost haunts in the great trees and their

smallest hiding places in the fresh, sweet-smelling grass. It sings softly among

the loose thatching leaves by the side of the hut, and murmurs pleasantly

through the fissures in the rocks and the light bushwood, at the entrance of the

forest dells. It is a messenger of pleasure—a welcome and familiar friend to the

happy people of the land. They go forth to meet it with joy, for it is the

harbinger, to the Islanders, of merriment and day.

Removed from the straggling village and some miles distant from the coast, stands a solitary habitation, in the pleasantest spot of the more inland portion of the Island. Its rude door is drawn back, but, as yet, no one passes the entrance. At last, a tame turtle-dove flutters out and is followed, in its morning flight, by a young girl.

Singing its soft, monotonous song, the bird flies over the white coral pavement before the house, over the garden plantation and meadowland and into the scattered wood, that stretches almost to the hill-side beyond. Carolling and laughing to herself, the girl still follows her companion. Her simple robe, disarranged by the rapidity of her motion, discloses a supple and delicate form, unrounded by maturity, as yet, but tempting to look upon, even now. Onward she wends, wherever her playmate leads her. Now, she lingers over the wild-flowers at her feet. Now, she starts up and looks for the presence, or listens for the voice of her gentle favourite. Now, she bounds rejoicingly along the pathways of the wood, or pauses, enamoured of its music and its brightness, by the streamlet that glitters at her side. Here, she playfully chides the briars and creepers that oppose her advance. There, she laughs with innocent delight, as soon as some small sudden peep of forest scenery, more beautiful than all she has hitherto beheld, appears before her. Bright and happy as at her setting out, looks she on her return, when she rests at last at her habitation and watches in the soft, clear distance, her favourite's homeward flight.

As she sits listening there, the sound, from the neighbouring vallies, of the cloth-maker's mallet, mellowed and harmonized by distance, rings merrily upon her ear. Now its pauses are filled by the noise of the woodman's axe—now, by the voices of the journeyers to the village beyond—now, by the rippling of the stream, that runs through the garden of the hut.

She looks downward to the pathway among the trees, that leads to the village. Beautiful, in her unrestrained inartificial attitude of repose, what Eve in her innocence, was to the Paradise around her, that seems she, to the charms of the land that she lives in and loves. The most artless gaiety and grace of childhood and the most alluring softness and bashfulness of youth, mingle on her countenance; whose attraction, appears not in regularity of feature, or fairness of complexion; but, simply, in the youth and innocence—in the enchanting variableness and suddenness of its every expression. No wearing and anxious contemplation's are her's. Her thoughts rise upon her mind, only to startle and delight, and never linger there long enough, to weary, or confuse. She is still as God made her; unpolluted by misery and unmarred by man.

Already, the village pathway is trodden by many feet. Some times, a company of women passes before her eyes, then bright-coloured garments glittering in the sunlight, that has already penetrated the spaces between the trees. Sometimes, a troop of fishermen are seen, bending beneath the weight of the spoil that they have taken in the night; and sometimes, a young warrior—impatiently furbishing his maiden arms and longing for the field of battle from his inmost heart—swells the ranks of the journeyers through the woodland avenue. All these, as they pass, the girl watches with careless delight, until a solitary woman appears among the trees; and then, an expression of the utmost interest and joy takes possession of her countenance, for she recognizes her one guide and companion, in the night-wanderer by the shores of the great Lake.

Slowly and wearily, Idía paces onward. There is a strange mournfulness at her heart as she gains the hut and returns Aimáta's impatient caress. There is a sorrowfulness, mingled with the gentleness of her expression, as she listens to the girl's animated narrative of her chase after the turtle-dove. A strange feeling of discomfort and inexplicable foreboding of she knows not what, is overcasting her mind, now that she is in her own abiding place. There is no visible reason for its assailing her, but it still hangs over her, in spite of her efforts for its removal. Is it an affectionate fear for the future of her young charge? Is it conscience hitherto unnoticed and unknown at last, asserting its existence within her? Is it a warning from her guardian angel of some calamity in store?— She sinks down upon the soft grass floor of the dwelling. Silent and abstracted, she notices not the pleasant array of fresh gathered fruits, that Aimáta is arranging before her. The girl proposes question after question, but remains unanswered still. She exercises many a cunning art, attempts many an innocent stratagem, to entrap her sorrowful companion into merriment as enduring and as lively as her own, but in vain. At last, she relinquishes her purpose in despair. She curbs her natural gaiety, and sitting down, she nestles her head on the bosom of Idía, and looking up lovingly and hesitatingly in her face, she invites her attention to one of the wild, poetical legends of the land; which, she had now perfectly acquired, and which she tells in a half whisper, sometimes, pausing to watch its effect upon the woman's demeanour. A tear has gathered in her eyes as the girl pursues her task, but she speaks not, moves not, yet; and the story-teller ends her tale, and is still unrewarded by success.

Alas! In the dark recesses around the Lake Vahíria, and in her midnight communings with Ioláni, the Priest, Idía has lost, for ever, the charm—once so treasured in possession of Aimáta and Home!

Chapter III

The Birth in Sorrow

Between the inhabitants of the lonely dwelling, there had sprung up, in spite of

disproportion in ages and difference in sympathies, the strongest attaching

ties. When only assumed for convenience sake, there is no hypocrisy so

perishable—when arising from mutual esteem, there is no sincerity so

encouraging—as female friendship; and this rare and beautiful affection existed

in its utmost truthfulness and purity, between the woman and her charge. Of the

parents of Idía, one had died, and the other had departed for the dwellings of a

distant, and stranger tribe. She had discovered the child Aimáta, forsaken by

her natural guardians, almost in her infancy, and had taken pity upon her

forlornness and sheltered and cared for her, herself. In a land, where the

domestic ties were often but carelessly recognized, such an event as the

abandonment of offspring—though uncommon, was not unknown; and Idía retained

undisturbed possession of the girl, up to the time of her introduction to the

reader. A better protector, the forsaken child could not have obtained; for as

yet, her guardian, had not lost the honest, affectionate sympathy of the people

of the land. She was beloved and reverenced by the woman, and but seldom

visited, by the merciless contempt, so frequently bestowed by the men, upon the

female population of this island. To the one sex, she was endeared by the

unvarying gentleness and humility of her demeanour. To the other, she was

estimable, in the earlier portions of her existence from her superiority

(apparent, though unaccountable) to the women around her; in the later, from her

intimate connexion with the high-born and powerful Ioláni, High Priest of Oro.

In this man, centered the one, important difference of feeling, between the

woman and her charge. For, persuade as eloquently as she would, Idía could never

conquer the girl's aversion to this presence and even the name of the religious

principal of the land.

This disagreement, fatal as it might seem to be, and might in truth have been, in many cases, wrought no evil influence on the attachment between guardian and guarded. Aimáta's aversion to the Priest, invincible as it was, was a sorrowful but never an insulting dislike, and awoke, consequently, pity and astonishment, rather than anger and contempt, in the heart of Ioláni's beloved. She was so submissive, so affectionate to her protector, so innocent and uncomplaining in the long solitudes she was now doomed to encounter, that to scorn or forsake her must have been almost too much even for humanity's refined capacity for crime. Such then were the positions of Idía and her young charge, in the season of their happiness, when their lives were in that dreaming monotony of pleasure, so spiritless when described, so delightful, when experienced. Her usual round of innocent amusements, still sufficed to occupy Aimáta's hours of solitude; and

Idía's meetings with the Priest, were as frequent and as undisturbed, as at the first. Thus, the days—those days to be spent in rejoicing to be remembered in woe—glided quietly onward. But a change was rapidly approaching in the fortunes of the girl and her guardian, and in the hour of travail, that was already at hand for the woman, lay its destined signal of commencement for both.

The day that ushered in the event which forms the subject of this chapter, was one of the most beautiful, of the beautiful season that still lingered over the islands of the South. At some distance from the dwelling of Idía, in a sort of half cavern, half arbour, lay sleeping—sheltered from the noontide heat— the girl Aimáta. The place was situated on a hill, and raised, by a rocky eminence, considerably above the regular and public footway. How its present tenant could have gained such a position, was a marvel; for there existed no visible means of ascent to the strange resting place she had chosen. In her restless slumber, her light clothing had become so discomposed, as to leave the upper part of her form—so delicate in shape, so enchantingly soft and dusky in hue—almost entirely uncovered. Her long hair, drooped over and partially concealed her neck and bosom. One hand, (on which she had pillowed her cheek) still grasped a profusion of the flowers she had gathered in the morning, some of which, clustered in exquisite confusion, over the lower portion of her countenance. The other, rested upon her hip, as if sleep had overcome her, at the moment when she had attempted to arrange the garment that had fallen from her side, in its appointed place. There she lay, in the beauty of innocence and youth! The worthy child of the softest of climates and the loveliest of earthly lands! Suddenly, however, she started from her sleep and hastily gathering her vesture around her, hurried to the entrance of the cavern.

Two well-known voices, raised in anger and agitation, had struck upon her ear, from the pathway immediately below her. She looked cautiously out. In a few minutes, Ioláni the Priest passed beneath; his swarthy countenance, terrible to look upon in its deep, concentrated expression of fury. She could hear him, muttering to himself and laughing horribly and unnaturally, as he sped onward in the direction of the villages on the coast. She waited until he was out of sight, and then, swinging herself down the almost perpendicular sides of her natural hermitage, by means of the bushes and projections of rock, with extraordinary fearlessness and agility; she ran forward, in the opposite direction to that taken by the Priest.

She had proceeded but a short distance, before she encountered Idía, standing alone, in a rocky recess by the roadside. The woman's deep, olive complexion had changed to a ghastly paleness; her eyes, wandered wildly backwards and forwards, over the landscape before her; and her hands were pressed on her forehead, as if a deep, dreadful agony had suddenly assailed her. The instant she perceived Aimáta, she seized her almost roughly by the arm, and dragging her close up to her side, spoke a few words in her ear in a harsh, moaning voice. The next moment, the girl fell at her feet and burst into a passion of tears.

What this intelligence was, and why it affected so fearfully both narrator and listener, can be only satisfactorily explained to the reader, by an instant's investigation of one of the few revolting points in the Polynesian character— the deplorable prevalence among the people of the crime of infanticide. This reproach to the nation, was intimately connected with, if not entirely originated by, a sect of licensed libertines who have existed, under different names, in the Pacific Islands, from the earliest known periods, and whose extraordinary institutions, it will be our duty to revert to, at a future opportunity. Among the rules of this atrocious society, to the prohibition of marriage among its members was added the regulation, that their children should be invariably destroyed at birth. This point of law among the Areoi body, in particular, soon became a point of convenience, among the people in general; either the poverty, the pride, or the barbarity, of the parents, being the three principal causes of the destruction of the offspring. If a man's possessions were but scanty, if the result of his labour, were precarious and trifling, the impossibility of rearing his children in comfort and plenty, was considered reason sufficient for their death, the instant they entered the world. If a chieftain of rank, contracted an intimacy with a woman from the lower orders of the people, the results of such a connection, were assumed unworthy of the father[']s care; and were, consequently destroyed at birth. In the case of a long war, when the ranks of the male members of the population decreased with ominous rapidity, this authorized system of infanticide, was of necessity, partially checked; as the number of children, that from motives of convenience, affection, or need, were generally spared, would, in such a crisis, be unable to supply the sudden and unusual deficiency. So thoroughly, however, among these deluded people, was natural affection overpowered by the insane dread of overpopulation that had induced the ruling powers to authorise infanticide in the first instance, that the frequent remonstrance and resistance of the mother, against the savage intentions of the father and the male relations, was regarded, either as a matter of ridicule, or of downright insult and offence; and the wretched parent, had the misery of seeing her offspring murdered before her eyes, unless she could by any means prolong its existence a quarter of an hour from its birth; in which case, the law decreed that it was thence forward to be permitted to live.

Such, (briefly analyzed) was infanticide in the Pacific Islands; and such was the crime, to which the Priest had tempted the wretched woman, who had entrusted to him her priceless though simple dowry of affection and truth. Her indignant and positive refusal of his iniquitous demand, instantaneously converted the careless cruelty of his intention toward his unborn offspring, into settled and malignant hatred toward the mother. The woman's charms, had long since, begun to pall upon him. Satiety—crime's safest pathway to the heart—had already urged him to cast her off; but so patient, so doubly affectionate, had she grown with him in spite of his scarce-concealed indifference, that even he, villain as he was, could not forsake her, without some shadow of a pretext. The opportunity for abandoning him she had now, provided, by her reception of his proposal, herself; and he seized it with impatience and delight.

But his evil intentions did not end here. The most dangerous period to the offender, is the half hour that follows the offence; for, though the heart create[s] enmity, it is the mind that perfects its work. Thus was it with the Priest. The triumph of having gained his end sufficed him in the honour of parting, but, no sooner had he addressed himself to his solitary journey, than other thoughts began to work within him.

He had been scorned and defied—he, the man of power and celebrity, whose nod had until now been a command, whose slightest word a law—and by whom?—By a woman!—By an inferior creature in the scale of beings—a household drudge — an appointed slave to the sensuality of man! The meanest husbandman in the island, would rage to have such an indignity as he—the brother of the King, the War-god's Prophet and Priest—had just undergone! She had not entreated for the child. She had not humbled herself to him for the favour of its life. She had threatened and despised him. It was too much to bear.

Revenge—safe, speedy, ample revenge—he was determined to have; but how should he effect it? Should he attempt the destruction of his child, at the hour of its birth? This, would be fulfilling his first object as well as satisfying his vengeance; and that, moreover, (as the custom of the country ensured) at no peril to himself. To think with him was to act and he immediately turned and retraced his steps.

In a short time, he gained the women's track, and as he halted for an instant, to watch them unobserved, another inspiration, more Satanic than the first, flashed over his mind.

The girl Aimáta, was now hastening to maturity. She was the woman's beloved— her comfort and delight in all seasons. She was innocent and fair and even now, in the first dawn of maidenhood. What a tool for his vengeance might he make of her! How admirable, here, would his lust second and sweeten his revenge! How surely would all that grief left unpreyed on in the detestable Idía, be thus devoured by jealousy! Here, was truly a tremendous and long-lived process of retribution discovered at last! Bide but the convenient time, and all was sure.

Be wary and determined in his attempt, and triumph and success must be his! Determining thus, the villain set forth again to dog the steps of his victims— now, lurking among the foliage, when they stopped to glance back; now, closing upon their track, when they entered the woods; now, falling far behind, when they emerged upon the plains; but never, for an instant, allowing either to escape his eye.

Meanwhile, the women had been as diligent in preparing for their safety, as the Priest in compassing their downfall. Helpless though Idía might be under the sudden infliction of misery that had befallen her, her helplessness was of the moment, alone. A stern determination had already grown within her, to preserve the child, though she perished in the attempt. The vileness of the Priest's proposal had horrified but had not overwhelmed her; and the desperation of purpose, of a woman whose affections have been outraged without cause, arose, erelong, to fortify her heart against everything that was selfish in emotion or motivated in thought.

And the poor girl—whose innocence, was already marked by the spider for his prey; who had been taught to expect a future companion and employment in the yet unborn child—even she seemed to have learned from the hour of sorrow, a determination beyond her years. Dependant upon others, as she had been all her life, by the force of circumstances, she stood forth at this moment a host in herself. In women, more universally than in men, the necessity for action generates the power. Their energies, though less various, are more concentrated and —by their position in existence—less over-tasked than ours; hence in most cases of extremity, where we deliberate, they act; and if, in consequence, their failures are more deplorable, their successes are, for the same reason, more triumphant and entire.

In a moment, Aimáta perceived that it was her duty now, to govern and not to obey. She led—almost dragged—the woman out of the highway into a track in the wood, that conducted along the hills toward a deep and distant ravine, bounded on one hand, by a precipitous mountain side, and on the other, by the vast tract of forest land which they had just traversed in effecting their escape. In the distance, at the opening of this natural division between mountain and mountain, you caught here and there, at chasms in the rock, bright, beautiful glimpses of the villages and country below, terminated by the sun-bright ocean that stretched out far beyond. Here, in a cavern formed by the juncture of several immense masses of basalt, Aimáta halted; for a strange presentiment had come over her that their footsteps were tracked by the Priest. She looked in Idía's face. A slight flush as if of pain or anxiety, overspread her cheek, and a low, half moaning, half sobbing sound, came from her lips; but she seemed as morally insensible—as incapable of speech, or perception as ever. The girl drew her towards a portion of the cavern overgrown with moss and wild flowers and breaking a cocoa nut that had fallen from the trees above, she fetched a little water in the shell; and kneeling down by the sufferer, comforted and wept over her.

And thus—patient and gentle creature!—when Death withers the softness on they cheek and the brightness in thy happy eye; when thy spirit lingers at parting from its loved and beautiful abode, and they that have rejoiced in thee, stand mourning by the side—thus, shall the ministering angels kneel round thy bed and comfort and weep over thee! The hours lagged on. The husband-man's axe was heard from the vale, and the harmonies of the breeze, from the verdure above. The shadows, one by one, began to appear upon the rocks, and the hot, dusky haze, had already vanished from the distant sea; but the fugitives yet lingered in the cave; and the sufferer, mourned, and the soother, comforted still.

A little longer—and the woman now moved restlessly backwards and forwards on her moss couch. Her eyes flashed and dilated. Her low wailings began to deepen into groans, and she tore at the moss and wild flowers by her side. Then, she raised herself a little and dragged her vesture from her bosom, as if suffocating with heat, beseeching the girl, in a piteous voice, to have mercy upon her—to bear with her yet a little while—to stay there with her till the hour of death ——

♣♣♣♣♣♣

Comfort it, care for it, Aimáta! There are none in the Island to welcome it but thou! Chide it not for its weeping, for its birth was in sorrow. The pilgrimage of earth is a pilgrimage of woe; what marvel then, that the journey at its outset, is undertaken with a tear? See how the sunbeams glitter on its form, how they stray over the delicate tracery of its little limbs, how they nestle on its round, dimpled cheek!—And the air—viewless though it is to thee—how gently, even now, is it stealing over the infant's bosom; how lightly is it hovering round the infant[']s lip! While Nature itself seems luring it to smile—Oh! who shall hesitate to aid so blessed an attempt!

The shadows had lengthened and multiplied; the cool land-breeze of night had already arisen upon the earth; and the sun was fast sinking in the distant ocean, when Aimáta, who was still foundling this child, suddenly stopped in her occupation.

There was a distant rustling among the bushes above. It might have been the fall of a cocoa nut or of a loose piece of stone. She listened again.

After a short interval of stillness, it sounded once more—nearer this time. This noise, too, was more protracted. She flew to Idía almost distracted with terror. The rustling was approaching, and her ear, practised in refined perception from her childhood, detected now, that the sound was caused by human footsteps. They spoke together for a few moments. The woman's tones were commanding and calm, the girl's agitated and imploring—The next instant, Aimáta disappeared with the infant, in the direction of the plains.

Idía raised herself and looked toward the opening. Suddenly someone obscured the last ray of sun-light, that was streaming through the mouth of the cavern. She knew him, at that distance, by his lofty and noble stature, and (as he came nearer) by the bitter scorn on his lip and the stern ferocity in his eye. It was the Priest.

"Away!, Away!" she cried, as he approached, "what dost thou here? Get thee to thy sorceries and thy gods; for the child is saved! That which was mine own, I have preserved in spite of thee! He is born! He lives! He shall grow in beauty and in strength! He shall shame thy heart by his comeliness when thou lookest on him! He shall speak in the councils of the brave! He shall yet go forth among the warriors of the land! He is saved! I have seen him! My beloved one, mime own!"

She laughed hysterically, and there was a terrible wildness in her eye, as she motioned him to be gone.

But he still came slowly on, muttering to himself, with a ghastly revolting smile on his lip, and an expression of mingled lust and ferocity in his eye. As he looked round the outer portion of the cavern, he hardly noticed the woman; and having completed his survey, he proceeded towards the inner recess. There was a pause—a brief silence; and then, she could hear him groping his way in the dark places beyond her and calling softly and enticingly—"Aimáta! Aimáta!"

A horrible suspicion flashed across her mind. She looked round towards the mouth of the cave. Where was Aimáta? Should the girl return, while the Priest was there!—It was too terrible to think of. She turned again to the dark recess. "Aimáta! Aimáta!" He was persevering in the search! She attempted to rise. She could just stand, when supported by the sides of the cavern; so she staggered, aiding herself by the projections of rock, to the entrance of her place of refuge; and there, she set herself to watch. If the girl returned back, she might make her a sign to fly, and so, she might yet preserve her.

"Aimáta! Aimáta["]! Even now she could hear his deep, quick breathing. In another instant, he stood by her side. As he looked on her, his fingers mechanically grasped at the air, as if he thought her already within his murderous hold. He advanced, clutched her fiercely by the arm, hesitated for an instant, and then, casting her from him, and laughing and muttering to himself, he passed from her sight in the direction of the high lands above; still calling, at intervals,—"Aimáta! Aimáta"! The sun had gone down. The brief Twilight of the South soon faded and passed away, and forth from the face of the waters rose the still, soft moon; but the girl came not. A long hour had passed since the departure of the Priest, and Aimáta had not appeared! Had he met her in the woods? Idía's heart sank within her at this thought. In miserable expectation and dread, she watched on. A few minutes more, and now, she saw by the moonlight, the figure of the girl advancing wearily and cautiously towards her from below.

She gained the cavern. Her long absence had but arisen from an excess of care. The infant was sleeping in her arms, and the bright, happy smile, had already returned to her innocent face. She stole softly up to Idía and placing her offspring in her possession, she kissed her cheek. At that action, its old gentleness and tenderness returned to the sufferer[']s heart; and a last, faint return, of the beauty that was vanishing from it for ever, flickered on her countenance, as she bent down her head and wept over the child.

♣♣♣♣♣♣

The End of Book I

|

Book II

—"Thirst

of revenge, the powerless will |

|

Chapter I

From Present to Past

Another year has passed over the

Island,

as Idía halted by the shores of the Great Lake, at the same spot as that

described at the introduction of this narrative, and almost at the self same

hour of the night. On this occasion, however, she was not accompanied by the

Priest, but by a woman and a child. After pausing for a few moments of rest and

deliberation, this little party entered a canoe that had been left on the shore,

and paddled softly and cautiously towards one of the extremities of the

Lake, where the rocks rose

precipitously from the very water[']s edge and the forests around them, were

most immense and impenetrable. On arriving at their destination, the vessel was

suffered to drift past the steps with the current, while the elder woman, seated

at the bow, minutely examined, by the help of the soft brilliant moonlight,

every variety in the precipitous shore, as they glided past it. Suddenly, she

made a sign to her companion at the other end of the bark; and the next instant,

by a stroke of the paddle, its sides grated against the jagged surface of the

rocks.

At this particular spot, the forest vegetation had found a bed of earth at the top of the precipice, and having taken in its luxuriant increase, a downward direction, it now hung so low, as almost to touch the waters beneath, and wholly to observe a wide natural archway, formed at this point, in the rock. Forcing aside, with great difficulty, these natural obstructions to their landing, the voyagers entered a little creek, whose strip of shingly beach had once been accessible from the forest beyond, by a wild gloomy dell.

At present, however, from the yearly and unrestrained aggression of briar and tree, this woodland cavity had become all but impassable; and the only practicable approach to the inlet now, was from the Lake.

From their hurried and anxious demeanour, the women could have had but one object, in seeking such a place, at such a time,—concealment. Having dragged the canoe upon the shore and safely disposed their small provision of baked bread fruit—two arduous achievements in such a situation as theirs, where the moonlight scarcely penetrated the tangled masses of bushwood overhead, and the actual space of dry land was contracted in the extreme, they sat down in their strange hiding place—the younger woman and the child, nestling together; the elder. . . . [text obscured in WC's hand] The reader will already have anticipated that Idía's companions in her vigil in the waterside, were no others, than the companions of her hours of misery in the lonely cave. Still a girl, in years and in feelings, Aimáta was now a woman in form and beauty. With her, Time had visited but to adorn; with the other two, his approach had been ever to harm. The child, at its birth so promising, was now weakly and diminutive in form, and strangely sad and un-childlike in appearance. Of the mother[']s former attractions, scarce a vestige remained. Her pale, pinched lips, sunken eyes and wan, haggard cheeks presented a mournful contrast, to her former self. There was the charm of expression in her still; but, the charm of feature, was gone for ever.

Ere, however, we proceed farther, it will be necessary to notice the more important incidents of the year that has passed, since the birth of Ioláni's ill-fated offspring.

Some day after the scene in the cavern, Idía and Aimáta departed with the child for another district of the Island; such a proceeding, being their only apparent prospect of escape, from the machinations of the Priest. By travelling only in the night, and keeping themselves carefully concealed in the day, they contrived to elude Ioláni's efforts to prevent their escape, with the utmost success; and reached their destination in safety. The part of the country they had chosen for their retreat, was governed, at the period of their arrival, by a young chieftain, as the representative of the authority of the King, whose ancestors had been celebrated, not only for their military prowess, but for their attachment and service to the crown, for several reigns. The present ruler, however, though lenient in the exercise of his authority, and beloved by the whole body of the people, was the secret but bitter enemy, of the reigning King and his principal assistant in the government of the Island. An insult from Ioláni, originated his disaffection to the royal cause; its confirmation, being occasioned by the refusal of the King (who acted under fear of his wily brother) to do justice to the injured party. The chieftain was too wise to resent this outrage immediately. He returned to his district without even a word of remonstrance, and patiently awaited the occasion for retribution; the time of Idía's arrival in his domains, being the time of his return from this unsuccessful application for justice, to the ruling powers.

The fugitives had remained long enough in their new abiding place, to enlist the sympathies of the people for the sorrows, of the one, and their admiration for the beauty, of the other, when Ioláni discovered their retreat, and imperiously demanded them from Mahíné, (their protector) as rebels against his authority, and insulters of his high and holy office. Delighted, at the opportunity thus afforded him of thwarting his ancient enemy, the chieftain refused compliance with the application of the Priest, until he had succeeded, before a council of the elders of the land, in proving his charge. It may be necessary to add, that Mahíné was further moved to this bold determinating by his attachment to this girl Aimáta, and his fears, from the known character of Ioláni, that if once delivered into his power, she was lost to him for ever.

Too chary of his power and influence, to trust either, to the perilous ordeal of false accusation, the Priest abandoned his first plan for obtaining possession of the fugitives. To expose himself as a sensualist, was rather to heighten than to diminish his reputation, among the sensual inhabitants of the land. But, to risk detection as a liar and hypocrite would be for one in his situation, a fatal mistake. His cunning still held the rule over his revenge, and he knew by experience that the safest guarantee of success, is to await the opportunity and not to make it.

It would have been an easy task for him, by using his influence with his brother, to have obtained by force, that which was denied to dissimulation; but, there were three valid objections to such a course of proceeding. The first, was the necessity of embroiling the country in war, by thus compassing his wishes. The second, was the loss of his popularity from the people's attachment to his victim; as well as the risk of his power and existence, should they be vanquished in battle; and the third—even supposing that might, would as usual, triumph over right—was the certainty that by thus satisfying his vengeance, he would secure rather a martyrdom for Idía, than a triumph for himself.

And here, let it not be supposed impossible, that so trivial an offence as Idía's, should excite in the heart of Ioláni, so deadly a determination for revenge. He was a man who either hated, or loved to excess. He possessed no inferior emotions; or rather, no emotion excited within him, was matured in mediocrity; if it past not away at its very birth, it at once became a dominant passion. In the present instance, mere indifference, immediately ripened into implacable hate. Whatever he now saw, or felt, affected him now, but in one way. Actions and incidents the most indifferent, he unwittingly distorted into direct encouragements of his own, absorbing desire. Sleeping, or waking, in labour, or in rest, slowly, surely and incessantly, he fed the fire that was burning within him. He had none to partake; and, consequently, none to weaken its intensity; for, it was a remarkable feature in his character, that he had never trusted a confidant, nor reposed himself on friend. The virtue of never betraying a comrade, is a common human quality; but, the virtue of never betraying oneself, is the rarest of superiorities. This accomplishment, necessary to a good man, is indispensable, to a villain; and it was possessed to perfection, by the Priest.

Neither let it be imagined, that in thus dilating, upon the political cunning, of the ruler and the talent for stratagem, among the people of the Pacific Islands, we represent a capacity for intrigue—a quick, ready intelligence of character, too refined to exist in any other than a civilised community. Wanting, as the inhabitants of Polynesia are, in all that is loftiest and most abstracted in intellect; in those mental qualities, that circumstances can originate and experience direct, they are far from deficient. Their policy, has had its Machiavelli; and their battle-field, its Caesar; though, their religion, has never possessed its Luther; nor their language, its Homer. As a nation, of the actual mental virtues, they have few, if any: of the doubtful, they have many if not all.

Foiled, but not intimidated, Ioláni departed from the chieftain's territory. Never had his reputation among the people, stood so high as at the present moment. The circle of Idía's partisans in her native place began already to narrow. It was given out, that the Priest had scorned to prove that, which should have been believed, from such a man, upon assertion. There was a rumor, that on his return from Mahíné's District, the King, indignant, at the chieftain's disrespect towards his brother, had offered him his army to lay waste the obnoxious territory, and that Ioláni had preferred rather to suffer the indignities that had been heaped upon him, than to embroil the people in war, and thereby, make the innocent suffer for the guilty. Such a thing had been unknown before. It as the first instance of consideration for human life, having overpowered the desire of satisfying private enmity, that had happened in the Island. Warriors of rank and renown, hurried to Ioláni in crowds, to offer him the service of private assassination; but, with the utmost gentleness and dignity, while their attachment was praised, the method they had taken to prove it, was severely rebuked. Soon, the Priest's conferences with his gods, became longer and more frequent; and it was whispered abroad, that his outraged dignity would be avenged by spiritual interposition, and not by the interference of man.

Meanwhile, in Mahíné's District, matters hardly went on so smoothly as usual. In his love-wanderings with Aimáta the chieftain was as gentle as was his wont; but, among his councillors and warriors, his manner became peevish and gloomy. His late triumph over Ioláni, had made him long for more important successes against his ancient enemy; and he chafed at the obstacles, that prudence, obliged him to offer to his own desires. He dropped vague hints on the imbecility and uselessness of the King, and on the advantage that would accrue to his people and himself, from an enlargement of their district. These hints were not lost on those to whom they were addressed; and the wise among the fighting men, began already, in secret, to furbish their arms.

The great mass of the people, too, though ignorant of the treason that was hatching among their betters, had become insolent and discontented, and, therefore, ready for the watchword of rebellion, whenever it should be called. Their chieftain's attention towards them, had latterly somewhat abated. Strange men had been seen wandering among them; and some, went so far as to declare, that Ioláni was of their number. There was a mystery about this which they could not comprehend, and this want of penetration on their part, and the evident existence of it on the part of the intruders, galled them to the quick. In addition to this, many of their war-chiefs, and of late, been more than usually vigorous, in demanding from their agricultural possessions, those tributes which an unjust custom permitted them occasionally to exact. These, and many other causes, contributed to raise a spirit of murmuring among them that Mahíné observed with delight, as adapting them admirably, to aid his seditious purpose. Victory over the King, would not only secure the ruin and downfall of the Priest, but gain him the throne. Ambition and enmity both urged him to attempt so glorious an achievement. He could count upon many of the disaffected from different parts of the country and from other islands. The muster of his own fighting men was—notwithstanding the long peace—considerable and effective; and he looked forward to the result of his enterprise as sure, could the suffrages of the people and the favour of the gods, be obtained ere it was commenced.

For some months more, matters went on as usual in the Island, until the summer had again come round, and the schemes, that Ambition and Vengeance, had so long and so craftily fashioned, were ready to work.

About this period, a personal application to the King was again made by Mahíné, in the matter of his old quarrel with the Priest. His petition, as he hoped and expected, was treated with disdain; and he left the royal dwelling, with the threat, that his own power should right him, as the mediation of the rules of the land, was unjustly denied to him, a second time. That same day, picked bands of marauders from the chieftain[']s district, made incursion on the territories directly watched over by the King, sacked and pillaged the dwellings of the industrious husbandman, with remorseless cruelty, and returned in triumph to their camp. The demand from head quarters, for their delivery to the government, was refused; and the messengers who bore the requisition, were beaten and most savagely ill-treated in the presence of the rebel chiefs. These acts of violence, were immediately avenged by the royal party. The once peaceful villages along the coast, became scenes of riot and bloodshed; and the peasantry, abandoning their possessions, crowded with their women and children, to the camps of their respective rulers. The King's flag was sent round the island to gather together his fighting men; Mahíné left no means untried to spread treason in the land, and the solemn preparations incidental to a commencement of war, were begun on each side.

A human sacrifice was first offered by both parties. By the one, to conciliate the gods in favor of their treachery; and by the other, to obtain their aid, in the righteous cause of defending King and country. Then, on Mahíné's side, might be seen the hurried and desperate preparations of men in rebellion, for the great crisis of their lawless attempt. Bands of desperadoes from other islands, athirst for blood, craving for slaughter, fighters for the great cause of carnage, landed at the shores and crowded to the rebel camp. The same utter recklessness of consequences, the same glory in the Present and defiance of the Future, animated all ranks and all tempers. It was terrible, to see the apathy of the gentler among the population—the women and children—to the prospect of rapine and bloodshed, that now opened before them. Among some, wild hilarity —awful at such a period—reigned supreme. Others, watched in stolid astonishment, the preparations for the battle. Here, might be seen a woman adorning with childish delight, the warrior[']s gear. Then, you beheld young girls hurrying joyously about the camp and increasing by their presence, the wild infuriate glee of the fighting men impatient for the battle. Hard by the streams of blood from the sacrifices, both of man and beast, were children playing in the horrible remnants of the offerings to the gods; their shrill cries, now drowned by the war of voices from the camp, now of the yells of the tortured men and animals, now by the screams by the half infuriate priests, prophesying success to the rebels and heaping the most hideous imprecations on the enemy's head. Then, in the distant wilds, startling the awful loneliness that hung over the forsaken villages, was heard the hurried tread of fresh recruits hastening to the camp. Forth from the woods and solitudes, their fierce countenance showing wan and ghastly in the moonlight, (for they travelled by night) tramped the husbandman, his bludgeon armed with shark's teeth on his shoulder; the chief, with his three-bladed iron-wood sword and his turban-formed fillet of cloth wound over his brow; and the young men, with their spears and slings. On they sped, singing their wild war-songs, and exulting in the prospect of the fight! Onward! onward! swelling with every hour, the ranks of ferocity and crime, they hurried to the gathering place; and the heart of Mahíné leaped within him, as he watched them pouring in, from the pinnacle of the camp! This scene of riot and debauchery, lasted for several days. The preparations for war—always complicated and many in the Pacific Islands—were, on this occasion, particularly dilatory, on both sides. The solemn observances, however, went on with the utmost regularity, until the final human sacrifice to commemorate the starting of the warriors, was all that was wanting, at last. With the King's party, at the period described above, the gathering for the battle was accomplished with comparative discipline and order. The confusion, usual among the people on such an occasion, was hardly observable in the royal camp, for the minds of the populace were concentrated upon one serious design— the apprehension of the last victim for the war-god; the doomed wretch, being no other, than the unhappy object of the former love and present enmity, of the great Priest.

While the altars were yet reeking with the primary sacrifices, he called together the whole mass of the populace, and commanded them, with fiery eloquence, to obey the requisitions of his god and capture, as the victim that was to close the ceremonies of war, the ill-fated Idía. He left no attempt untried to arouse their passions and to flatter their bravery and cunning. He represented his former unwillingness to avenge himself of the woman's offence, as the result of a direct communication from the idol, commanding him to reserve the ill-doer for its own will and pleasure. He solemnly declared, that the appointed hour was now come, that the god called for this sacrifice at last, and that their success in the battle that was near at hand, depended upon that offering alone. The effect of his appeal was instantaneous. The wild energy of his language, the mingled dignity and agitation in his demeanour, his poignant outward sorrow, that the idol could only be appeased by the death of one whom he had once loved, and now sincerely pitied and forgave, fired the hearts and aroused the reverence and the superstitious crowd around him. Detached parties of the most experienced spies that the camp possessed, started off immediately, to the stronghold of the enemy. Alive, or dead, they were determined to possess themselves of the victim, though they openly hunted her to the rebel ranks.

Two days passed away; and on the third, the pursuers returned, dispirited and shamed. They had, at first, attempted to capture the woman by stratagem, in order that she might be slain in triumph at the altar of the god; but their effort had been of no avail. They had then, openly attempted, by bribes, to incite the more disaffected of the villagers, to the betrayal of her hiding place; but, the answer of everyone they attempted to corrupt, was the same— "She has left their camp, and they knew not whither she had gone". That she could have escaped from Tahíti, was impossible; for the King's canoes had, latterly, watched the ocean round Mahíné's territory, to intercept all communication with the neighbouring islands. On their way homeward, they had searched every lurking-place with care; a few of their comrades, who were still on the watch, might discover the victim yet; but, for their parts, they had utterly failed.

And but little wonder was it, that their undertaking proved abortive. While Ioláni had sent forth his spies, Mahíné had not been idle, in using the same advantage, with regard to the councils of the King. His emissaries, had attended the Priest[']s convocation of the people, and, without delaying to hear more than the main point of the harangue, hurried back with new intelligence to the rebel camp; for, they judged that the chieftain, from the woman's intimate connexion and great influence with his beloved, would be anxious to preserve her from the vengeance of the relentless Priest.

They had deemed right. Mahíné, the moment he heard their tidings, commanded the presence of Idía and her companion; but neither were to be found. One of the spies, had incautiously communicated his intelligence to some idlers round the outskirts of the camp. It had spread with wild rapidity, from one to the other, & had reached the ears of Idía and the girl. They were sought for by order of the half distracted chieftain, but without success. It was supposed, that they had taken advantage of the confusion in the village, and effected their escape. All that could be discovered of them, was the little that was soon afterwards gathered from a half-witted old man, who declared, that he had seen them pass him on the borders of the forest, and that he had been commanded, by the woman, to take this message to Mahíné—"Be of good courage; I am guarding her for thee; battle it quickly and stoutly, and Aimáta shall be thy reward." The rescue described at the commencement of this chapter, will sufficiently hint to the reader, the destination of Idía's flight. Horrified at the crime and confusion attendant upon the preparations for war, and fearing for the innocence of the girl, among such a host of wretches as surrounded her, she had for some time contemplated taking refuge from the uproar of the villagers in the silence of the woods. The intelligence of the fate in preparation for her, immediately determined her in this purpose. She was appalled, but not overpowered, at so terrible a display of Ioláni's malignity. Danger and distress had done their utmost for her, and whatever their form, they now came as companions and not as strangers. She felt her position in an instant. None knew so well as she, how deep and how successful was the cunning of the Priest. When dependant for protection on others, she was open to betrayal; but, when trusting to herself, she was sure that her concealment was safe from discovery, either by force, or fraud, and could be frustrated by chance alone. She only waited to consult the wishes of Aimáta, whose situation was less perilous then her own, before she set forward on her flight. The girl, terrified at all she saw and heard under the protection of her lover, hesitated not an instant in her choice; and they started for the woods, together.

In choosing Vahíria as her place of refuge, Idía seized her only chance of preservation from the impending danger. There were caverns by the shores of the Lake, known only to the Priest and herself; and as there was but little chance, at such a critical period for his country, that Ioláni could be spared to prosecute the search himself, this was the spot of all others, that offered them the greatest security. For some days, they lurked about the different nooks and crannies by the waterside, gathering, as best they might, a scanty supply of provision; and that labour accomplished, they betook themselves to the strange hiding place, described at the beginning of the present chapter.

Ioláni, though furious at the result of his undertaking, was neither discouraged, nor dismayed. He saw that the ill-success of the search for the victim, had diminished the interest of some, in the sacred ceremonies, and had dispirited others. To risk a battle, now, was, consequently, almost to ensure defeat. He found, from intelligence received from the spies, that the enemy had concluded their offerings and were on the point of marching upon him. A consultation was held with the chief warriors, the result of which, was the organisation of a strong party of skirmishers, picked from the desperadoes of the forces, for the purpose of embarrassing the advance of the rebels. To this band, the slightest prospect of pillage and bloodshed, was as sufficing an incitement to engage, as was the ascertained favor of the god, to the general members of the army. After having proceeded about ten miles, (half the distance between the two districts) they encountered, in the wilds of the forest, the first rank, or advanced guard, of the enemy. Assisted by superior knowledge of the ground, they slaughtered them to a man; and the main body of the insurgents, ignorant of the actual number of their assailants, and unable to act in any force in so confined a space, were seized with a panic and retreated to their stronghold, in great confusion. This good fortune, seemed to secure Ioláni's success in the object dearest to this heart. In all probability, considerable time would elapse, before the rebels were again enabled to take the field; and in that period, ample opportunity would be afforded, to hunt down the fugitive and sate his revenge. The people were more than ever devoted to his cause. They

looked upon their success in the skirmish, as a direct manifestation of the favor of their god; and the cry for the victim, rose louder and louder, among all ranks. On the evening of this day of victory, Ioláni commanded a second attendance, on the following morning, before the Temple walls, to hear the result of another supplication to the god and to ascertain if he still willed the sacrifice of the victim he had demanded on the former occasion; for, the Priest declared that his hope of saving the woman, by appeasing Oro with other offerings, was the sole motive of his venturing a second application to the oracle of War.

So far, then, had this intricate entanglement of events advanced, when the populace prepared on the eventful morning, to attend the solemn invitation of the Priest. A reckless triumph and delight ruled all their hearts, and the once formidable insurgents, were now thought of with disdain. How wise this contemptuous estimate of the energy of the rebels, will hereafter be seen.

Chapter II

The Answer of the Oracle.

The building consecrated to Oro, the deity of the battlefield, was, in outward

appearance, simply, an extensive mass of heavy stone wall; saving, on the side

nearest the sea, where a sort of pyramid of huge stones, ascended by steps,

rugged steps, broke the otherwise monotonous regularity of the structure. On

this elevation, were placed the images of the inferior idols of war, which on

great and unusual occasions, were displaced for the feared and formidable idol

of Oro, himself. It was generally understood by the people, that the sacrifice

they hoped to behold, was to take place immediately in front of this erection; a

method of proceeding, adopted by their wily rulers of the land, on account of

its originality, and consequent power of producing unusual excitement in the

hearts, and unusual reverence, in the demeanour of the assembled populace.

The absence of great attraction in the Temple, itself, was fully compensated by the exquisite beauty of its situation. It stood about a mile from the sea-shore, where a slight rising in the ground, gave it an imposing and commanding position. The borders of the sea —in general studded with rocks—were, at this particular spot, bare of any such appendage; and the view of the noble ocean, already speckled thickly by canoes, was uninterrupted. Between the beach and the green sward before the Temple, lay the gardens of the natives, beautiful in their adornments of fruits and flowers, and contrasting delightfully, with the sameness of the smooth sands beyond. Then, came the delicious calmness of that portion of the sea protected by the coral reefs, and farther on, making a break in those natural guardians of the shore, lay two little islands, far out on the ocean—each with its canopy of tall cocoa-nut trees, and its surface of cool, pleasant verdure; and then, farthest and noblest to the sight, its limitless expanse of waters, gleaming in the glorious sun-light, and its mighty waves soaring in triumphant grandeur over their sturdy barriers of rock, stretched the magnificent Pacific.

Strangled with moss and wild flowers, and topped with every variety of foliage, the rocks that on either side, girded the distant shore, wore an aspect of softness and fertility that blended enchantingly with the milder characteristics of the inland scenery. The immense tracts of woodland that backed the Temple, broken here and there, by the appearance and footpaths, formed a pleasant prospect, in their coolness and repose, after the glare and animation of the sea-ward view; while, the mountains afar off, beautified by the distance, and surrounded by the smooth fertile hills, lost their barrenness and looked sunnily and softly down, on the happy vallies at their feet.

And, now that the sun had fairly arisen over this gay and beautiful place, sauntering carelessly along the paths and avenues, the population of the district wended towards the Temple. The bare-headed old man and the flower-crowned girl; the warrior in his vesture of brilliant red and yellow and the young mother in her garments of simple white; trooped happily onward from every passage in the woods, and arranged themselves before the altar of the war-god. No sign, however, of the commencement of the ceremony appeared as yet; and the light-hearted people, straggling downwards towards the gardens, betook themselves to their amusements without a gesture of impatience at the unexpected delay.

What thought had they, for the solemnities they had assembled to witness? The Past and the Future were nothing to them—the Present, was all they troubled themselves for, and trying must it be, if they met it with a complaint. Idía and her flight, were alike forgotten, in the freshness and sunshine of the morning; and the miseries of the battle to come, were veiled and hidden in the animation and gaiety that preceded its approach. What to them were the tears of days gone by, and the grief that might still sadden their dwellings? They lived and laughed on at the rise of the day; and there, was their armour of proof, against the ills that might happen at the fall.

On they straggled; some, to their repose in the shade; some, to their morning[']s bath, in the fresh water streams, that ran downward to the sea. Forth sallied the old, to their seats on the turf, and away went the young, to their love-walks in the avenues. Fresh comers, gave every instant fresh animation to the scene. Every one joined freely in the divisions of his neighbours, whatever their character might be; saving, indeed, the chieftains of rank, who walked gloomily apart, pondering their plans for the approaching battle. The laughter and confusion in the place, were at their height, when the sounds of wild singing, in the distance, arose even over the noise and tumult of the assembly before the Temple.

Instantly, the dancers paused in their revolutions, the old men started from their seats, the lovers hurried from their hiding places, the bathers forsook the water, the mothers and children emerged from their sports in the shade, and the surf-swimmers, who were just setting out for their dangerous diversion, turned and made for the shore. Oldest and youngest, gravest and gayest, as if by one common impulse, arose and hurried in the direction of the wild, unruly voices.

In another moment, leaping and raging onwards like maniacs or daemons, the mysterious Areoi fraternity (the wandering players of Polynesia) emerged from the avenues; and, driving back again the impatient crowd until they halted on the lower part of the green sward, prepared for their wild representation. This band of libertines, had more the appearance of evil spirits, than of

humanity. Their bodies, were daubed over, in the most grotesque and, at the same time, the most revolting manner, with charcoal. Their faces, were disfigured by a bright, scarlet dye; and their heads and waists, were ornamented with wreaths of beautiful yellow and scarlet leaves. To the evil influence and example of these purveyors of popular amusement, may be attributed all the worst features of the Polynesian character. Revered as sacred and the direct descendants of gods, their worst crimes and exactions, passed unchecked and unavenged. Their lives one unbroken round of insolence and iniquity, they wandered from district to district, exhibiting their strange performances, as the privileged panders to the worst vices of human nature. On this occasion, the present, was their farewell visit; for, the extraordinary preliminary ceremonies that harbingered their representations, were already preparing, in another and a distant portion of the island.

Loud was the laughter of the reckless populace, as one of the band, commenced the entertainment, by a speech of the most vehement eloquence, ridiculing the approaching war and its principal actors on both sides. Satire on public events and public people, was the most darling of their privileges, and on the present occasion, they used it with an unsparing hand. The address, was followed by a sort of chorus chanted with extraordinary rapidity and animation by all the members of the troop; and that ended, they arose and commenced their final dance.

Whirling round and round, in the most intricate evolutions, their motions, gross though they were, were hardly revolting, from the wild, picturesque grace of every movement. Ever startling, every varying, the most refined profligacy of civilised countries, could invent no luxury, more dangerously fascinating to the general eye, or more fatally destructive to the general character, than the mazes of the Areoi dance. Fatigue seemed to be as unknown to the performers, as satiety, to the audience. Old and young-men, women and children, crowded round the band, watching with noisy delight the half grotesque, half fearful exhibition, before them. Wilder and wilder, grew the movements of the dancers; shriller and shriller, rung their discordant music on the air; and louder and louder, still, rose the applause of the beholders. Hard to be imagined, and harder to be described, was the tumult of the scene, at this moment. Furious as the mirth had now become, its desperate character, seemed but little likely to retrograde, notwithstanding the amazing protraction of the amusement. The orgy, indeed, might have continued almost without interruption, until far into the night, but for the appearance, at this moment, of one of the inferior Priests on the Pyramid of the Temple, whose presence, without, at that period of the day, seemed the earnest of a speedy delivery of the answer of the oracle. Accordingly, the volatile crowd, the instant they perceived him, immediately quitted their mad entertainment, and hurried with strangely altered demeanours, towards the scene of the more important ceremony.

Saving, when a low murmur occasionally rose from their ranks, the assembly were now completely hushed. After another interval of expectation, the patience of the populace was at last rewarded by the appearance of Ioláni, upon the sacred pinnacle.

To the utter astonishment of the multitude, his demeanour was distinguished by a calm solemnity, strangely at variance with the accustomed raving fits of the Priests, upon delivering the commands of the oracle. There was something in his motionless, commanding attitude, and his elevated and solitary position, that awed the bold and terrified the faint-heated, among the audience assembled beneath him; and many a tradition of priestly power and priestly oppression, arose on their memories, as little by little, they reverently fell back from the immediate precincts of the sacred place, and silently awaited the address of the greatest among the ministers, of their tyrannic and mysterious religion.

For the first few minutes, Ioláni directed a penetrating and angry eye over the crowd beneath him. Then, advancing a few steps, in sorrowful and solemn tones, he spoke to the assembly this:— "Mowin, people of the land, your houses and your possessions, your happiness and your honor; your wives and all they that ye have loved; for, still is Oro unappeased, still is the altar vacant, still is your native earth, unhallowed by the blood of the sacrifice"! "I stretch forth mine eyes: and lo! the men of valour, who have trodden the mountain labyrinths from their youth, but are weary of tracing them now. I look down upon the concourse of the people: and behold! by twos and threes assembled, they who have boasted in the camp of their cunning, who have proclaimed their frustration in the councils of the wise; but, where are their wiles in the hour of need? Are they left to Idía, in her hiding-place among the mountains? Are they departed at the voice of the sorcerer? Or lodged with the women and the little children of the land"? "Seek her! Seek her! Is there no encouragement in the victory in the woods? Is there no incitement to obedience to Oro, in that success, so unhoped for, and yet so complete? Will ye forsake your god, ye that are devout, when he has battled for ye unpropitiated? Will ye be foiled by a woman, yet, ye that are brave—that are terrible among the warriors of the land"? "Who is there among ye that fears not death, if shame write the epitaph on your tomb? Which of ye desires life, if dishonour darkens your house and division haunts ye, wherever ye go"? "Yet so shall it chance with ye all, if Oro is unsatisfied. Think not, that because ye have conquered in the skirmish, in the great battle to come, ye shall conqueror as well. The god has encouraged ye at the first, that ye might the better obey at the last. Not as an earnest of victory, was the fight in the wood; but, as a command of submission to the will of the spirit of War".

"For, behold, Mahíné is cunning, and the hearts of his warriors, are athirst for the contention even now. The first tree that ye fell in the forest, doth it vanquish the stubborn resistance of the rest? The first rank of the rebels that ye have slain, hath their destruction exterminated the power of the mighty army behind? In the great and terrible battle to come, shall ye need no inspiration but your hatred? No aid but your weapons of War"?

"I turn mine eyes towards the waste of ocean; and lo! arising still and stealthy from its surface, the morning wind streams over all the earth! The flowers, in their beauty bow to its victorious approach! The leaves of the forest, in their multitude, are moved and scattered by its swift advance, over the noble mountain-tops and down in the secret corners of the vallies and rocks, it wends ever onwards. It passes over all. It is turned backward by nothing on the earth; and so, rejoicing in its might, it vanquishes the obstacles of the land, and behold it forth once again upon the wilderness of waters beyond"! "So, from their far district, arise stealthily the hosts of the enemy. So, (the War-god unappeased) shall your women, in their beauty, yield to the will of the oppressor. So, shall your warriors, in their multitude, be dispersed at the advance of Mahíné's victorious band; and so, prevailing through your coasts, shall they reach again their homes in security and triumph!"

"Despair not, weary not, then, in the search. Alive or dead, hunt but the victim down and all will yet be well. Produce her before the Temple walls, and the enemy shall fly before ye. The fairest of their women and the best of their possessions shall fall into your hands; and the proudest of the rebel chiefs, shall surely be humbled at your feet; for in a vision of the night that is past, the War-god hath promised me thus"!

Here the Priest paused for a short time, to watch the effect of his harangue upon the multitude beneath him. Saving, however, when the lamentations of the women, or the low wail of some terrified child rose occasionally on the air, the utterest silence reigned over the auditory. The men, in groups apart, either crouched silently on the earth, or paced sullenly round the outer most core of the crowd. Ioláni's address seemed to have taught them, rather to prepare for the defeat, than to ensure the victory; and the same ominous and dogged despair, was expressed in the demeanours of all.

In a few minutes (and now in fiery and agitated tones) the Priest again spoke. "Do the warriors despond"? cried he. "Is determination departed from the brave? Arise once again! Pursue and despair not; and the victory shall yet be yours"! "For I—even I the beloved of Oro! The companion of the god! will head ye in the search. Led by the spirits of your fathers, guarded by the Arbiter of the battle-field, cunning has no power to baffle, nor danger to weary me! Let the young men arise and come forth! Let the aged and the feeble, remain and supplicate here. Tomorrow's sun—by the glory of Oro I swear it!—shall rise over the altar, to illumine the sacrifice at last"!

The effect of these words was electrical. The men with one accord started up and crowded round the pinnacle, from which, Ioláni had addressed them. To be headed by him, was an earnest of success to all, and a proof of enthusiasm for the cause of the god, never vouchsafed by a dignitary of the land, before.

Wonderful, as an example of the iron tyranny of superstition over the heart, was this man's influence over his people. Not a word fell from his lips, but was regarded as a direct inspiration from another and a nobler world; and while the despondency characterizing the first portion of his harangue, had sunk his audience to the lowest depths of misery and despair, the energetic boasting of the latter, had, strange to say, the power of effecting in their feelings, a revolution, the most instantaneous and the most complete.

Nothing could at this moment, equal the enthusiasm of the assembly now. In an astonishing short space of time, the fighting men and spies were mustered, the sentinels placed, the women and children driven from the ground, and their distinct bands of pursuers organised; the most numerous and disciplined of which, was instantly headed and led by the wily Ioláni, in the direction of Vahíria.

The sun, that night, went down in thick, angry clouds; and, as the concourse separated and sought their homes, the old and the experienced, foretold an approaching storm.

Chapter III

The Pursuit

If ever Ioláni tasked his energies to the utmost, it was upon this occasion.

This, was his last chance for vengeance on Idía and for the preservation of his

credit as oracle of the War-god. Upon his success in the pursuit, he had now

staked his all; and he determined that the struggle should be tremendous, before

he lost. Every responsibility, now rested upon him alone. The little power of