1889

Harper's Weekly

|

|

|

Francis Whiting Halsey (1851-1919) was an editor and writer and it is

unlikely that he met Collins. The account of Wilkie's life contains some

errors and his analysis of his work is fairly derivative. This obituary

appeared in Harper's Weekly on 5 October and was an opportunity to

promote the Harper edition of his works and republish a fine engraving of

him. |

WILKIE COLLINS.

The death of Wilkie Collins in

London on

September 23d removes from the company of active novelists one of the oldest and

most widely read. His career to a large extent was contemporary with the careers

of Thackeray, Dickens, Charles Reade, and George Eliot. Born, as he was, in

1824, when Thackeray was only thirteen years old, Dickens only twelve, and

Charles Reade only ten, he has survived Dickens by nineteen years, and Thackeray

by twenty-five. Mr. Collins’s literary activity extended over a period of

forty-one years, or from 1848, when he published a life of his father, William

Collins, the artist, down almost to the month of his death, when he was seeing

through the pages of the Illustrated London News his story of “Blind

Love.” Wilkie Collins was one of the most industrious of modern novelists. The

regrets awakened by his death must extend throughout many lands and peoples. He

was not only read widely, in England, America and Australia, but he was well

known in France, Italy, Russia, and Germany. So long ago as the date of his

No Name (1862), his stories had been translated, read, and admired in the

languages of those countries.

Mr. Collins was reared in the midst of

artistic associations. Besides having an artist for his father, he was indebted

to another for his Christian name, while a sister of his mother was Mrs.

Carpenter, the painter of portraits. And yet it does not appear that the boy’s

relatives ever had a purpose to devote him to one of the Muses, artistic or

literary. They sent him for a time to a school at Highbury, and again to

a school on the Continent. French and Italian he acquired in his youth, and was

able to speak as well as write them. Among his school-mates in

England

he was a source of jealousy on this account, and they persecuted him as a

foreigner. His only means of relief from this treatment is said to have been an

alliance with the strongest boy in the school, who engaged to punish those who

assailed him on condition Collins should tell him entertaining stories. Thus, in

the school of early adversity, were first stimulated the talents of the future

novelist.

Possibly it was a conviction on his parents’

part that neither art nor literature could afford their son a road to affluence

that led them to select for him a commercial life. They articled him for four

years, as soon as he had left school, to a London house engaged in the

tea trade, and doubtless pictured to themselves the time when he should become a

prosperous merchant. But in commercial life boy gave no promises of success; it

was distinctly seen to be not his forte. He was then placed in a lawyer’s

office, where he remained until his father’s death in 1847. Wilkie Collins was

then twenty-three years old. A year later he produced his first work in

literature—the biography of his father. This publication comprised two volumes,

and contained selections from his father’s correspondence.

Whatever were the merits of the performance, Mr.

Collins, after that first taste of the charm of literary labors, speedily fixed

upon something for his vocation more congenial to his taste and talents than the

drudgery of it clerk’s life in a London law office. Two years later he appeared

before the public as a novelist with his Antonina; or, The Fall of

Rome.

That success should have attended him at a time when Dickens was in the

flood-tide of his fame, and when Thackeray had just published his Vanity Fair

and Pendennis speaks more than anything else can for the powers that lay

in him. Surely it was a fair inference that this man would be heard from again.

It was singular that the year in which

Antonina appeared should be the year in which Dickens started his

Household Words, for with Household Words and its successor, All

the Year Round, the fame of Collins, like the fame of Dickens, will long be

associated. It must always stand for a mark of Dickens’s judgment, no less than

of his professional generosity, that he early saw and employed the talents of

the younger writer. Basil and Hide and Seek followed Antonina.

The latter of these two books found for the author a new admirer in

Macaulay. Dickens was more than ever impressed, and he asked Mr. Collins to

become his contributor. Accordingly The Dead Secret made its appearance

in Dickens’s periodical, as did other stories of his back in the fifties, the

most memorable of them all being The Woman in White, in 1859. After

Dark and The Queen of Hearts belong also to this period.

|

|

The reputation they made for

him in England spread rapidly to America and the Continent, until his

readers could be found in almost every civilized country. Following his

No Name, of 1862, came, in 1866, his Armadale; in 1868, The

Moonstone; in 1870, Man and Wife; in 1872, Poor Miss

Finch; in 1873, The New Magdalen; in 1875, The Law and the

Lady and, Alice Warlock; and in 1886, The Evil Genius and

The Guilty River. These comprise the better known of Mr. Collins’s

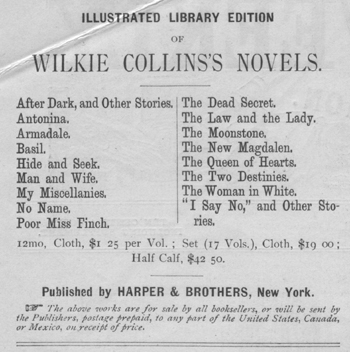

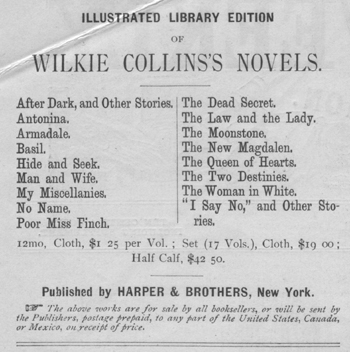

works. Most of them, along with a few shorter works, compose the Harper

Illustrated Library edition in seventeen volumes, other works of his being

issued in other form. |

None of these novels is better known than The

Woman in White, none made a more profound impression at the time, none is

still so vividly remembered by all who read it. In the character of Count Fosco

Mr. Collins made a distinct addition to the world’s stock of famous creations in

fiction. Already it has lived for thirty years, and another generation of fame

at least seems to be assured for it. Mr. Collins has said that he chose a

foreigner for this character because the crime was “too ingenious for an English

villain.” Mr. Collins’s villains were not of the coarse and stalwart type. He

knew how to draw a villain who could seem a gentleman and often pass for one,

who could appear well in a drawing-room, and seem at home astride a horse in

Rotten Row. For readers who liked him best, he painted the life of a world which

they had seen, which they understood and were parts of. But it was in his plots

that he most excelled. For this part of the novelist’s endowments he had an

astonishing faculty. The powerful interest of his novels always lay in the

mystery that was continued to the end of them, and in the art by which the

reader’s attention was held fixed and curious through the succeeding chapters.

Some of the qualities in which the greatest novelists have excelled, and which

Wilkie Collins distinctly lacked, need not be enumerated here; it is enough that

he possessed a genius for plots and ingenious mysteries in which few writers of

any age have surpassed, if, indeed, they have equalled him.

Mr. Collins’s visit to this country in the

winter of 1873-74 will be remembered by thousands who heard him read two of his

shorter stories, The Frozen Deep and The Dream Woman. It was a

visit that gratified him greatly. Personal letters to his publishers, which are

still preserved by them, bear excellent and unmistakable witness to this. One

dated from Buffalo, to which city he had proceeded from New England

by way of Montreal and Toronto, contains

the following: “Wherever I go I meet with the same kindness and the same

enthusiasm. I really want words to express my grateful sense of my reception in

America. It is not only more than I have deserved, it is more than any man could

have deserved. I have never met with such a cordial and such a generous people

as the people of the United States. Let me add that I thrive on this kindness. I

keep wonderfully well.”

Mr. Collins was a man of small stature, stooping

somewhat in the shoulders, but with large eyes and a round, genial face, framed

in by heavy hair and beard, that ill late years were almost white. He leaves few

relatives; neither wife nor child is among them. He died in the presence only of

his physician and a house-keeper, who had been in his service for thirty years.

His physician was Dr. Carr Beard, now an old man, and in his time an intimate

friend of Dickens. He is one of Mr. Collins’s executors.

Mr. Collins’s career illustrates once more the

truth that genius, once a man actually has it, will find its way. If genius for

any one thing is in him, it must come out of him. Born to be a novelist, he

cannot be made a merchant, and there is in him no future lawyer. A novelist be

will be. The singleness of purpose with which Wilkie Collins’s whole life was

consecrated to novel-writing re-enforces the truth of this statement. No other

objects claimed his devotions. He took to himself the warning of Lord Bacon: “He

that hath wife and children hath given hostages to fortune.” He accepted as his

supreme obligation duty to his art.

FRANCIS W. HALSEY.

From Harper’s Weekly 5 October 1889

XXXIII No.1711 p799

go back to biographies list

go back to Wilkie Collins front page

visit the Paul Lewis front page

All material on these pages is © Paul Lewis 1997-2007