1884

Recollections and Experiences

|

|

|

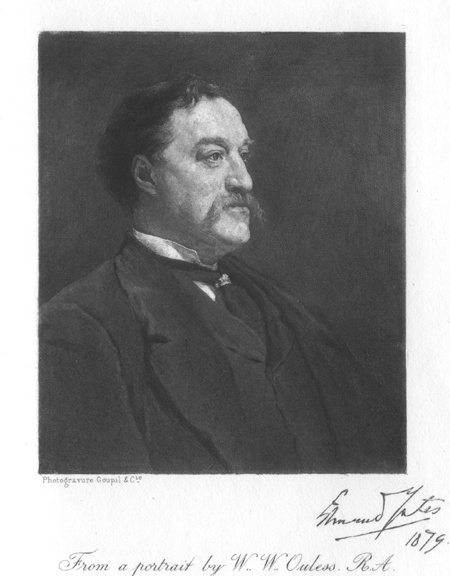

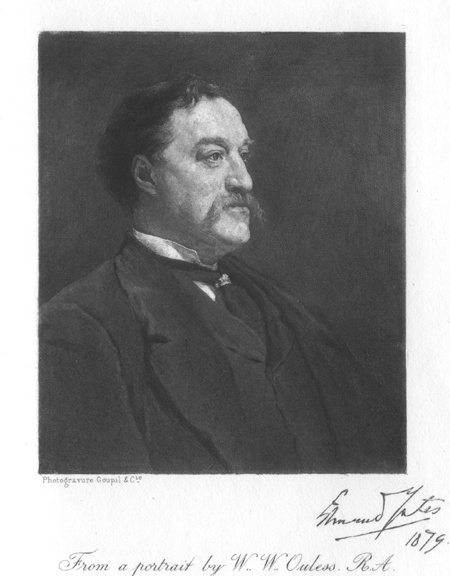

Collins's friend Edmund Yates (1831-1894) gives relatively few mentions

and stories about him in Edmund Yates: His Recollections and Experiences

published in 1884. These extracts give them all with their context,

including references to Household Words, The Lighthouse,

Yates's expulsion from the Garrick Club, Dickens, his departure for America,

and a letter from Elizabeth Braddon. |

And just about then appeared the

first numbers of Household Words, which I devoured with extreme

eagerness, and the early volumes of which still appear to me, after a tolerably

wide experience of such matters, to be perfect models of what a magazine

intended for general reading should be. In them, besides the admirable work done

by Dickens himself—and he never was better than in his concentrated essays—there

were the dawning genius of Sala, which had for me a peculiar fascination; the

novels of Mrs. Gaskell; the antiquarian lore of Peter Cunningham and Charles

Knight; the trenchant criticism of Forster; the first-fruits of Wilkie Collins’s

unrivalled plot-weaving; the descriptive powers of R. H. Horne, who as a

prose-writer was terse and practical; the poetic pathos of Adelaide Procter; the

Parisian sketches of Blanchard Jerrold; the singularly original “ Roving

Englishman “ series of Grenville Murray; the odd humour of Henry Spicer. (I

215-216)

…

Visiting relations had, in the mean

time, been established between us and the Dickens family, and we were invited to

Tavistock House, on the 18th of June, to witness the performance of Wilkie

Collins’s drama, The Lighthouse, in which the author and Dickens, Frank

Stone, Augustus Egg, Mark Lemon, and the ladies of the family took part. My

mother, who went with us, told me that Dickens, in intensity, reminded her of

Lemaître

in his best days. I was much struck

by the excellence of Lemon’s acting, which had about it no trace of the amateur.

At the performance my mother was seated next a tall gray-haired gentleman—a most

pleasant talker, she said who proved to be Mr. Gilbert a’Beckett, the magistrate

and wit; and in the drawing-room afterwards there was a warm greeting between

her and Lady Becher, formerly Miss O’Neil, whom she had not seen for many years.

It was a great night for my mother. She renewed her acquaintance with Stanfield

and Roberts, and was addressed in very complimentary terms by the great John

Forster. Thackeray und his daughters, Leech,. Jerrold, Lord Campbell, and

Carlyle were there. (I 279-280)

…

It was in the third volume, too,

that I first began a series called “Men of Mark,” which in style and treatment

was really the forerunner of the “Celebrities at Home,” and the first examples

of which were Dr. Russell and Mr. Wilkie Collins. (I 337)

…

The General Meeting was held the

next day. Neither Thackeray nor I attended; but the Committee were there in full

force, and, with the exception of Dickens, voted to a man in their own favour.

As an amendment to a resolution declaring that the Club had nothing to do with

the subject at issue between Mr. Thackeray and myself, the following resolutions

were proposed by Mr. James Cornelius O’Dowd, now holding an appointment under

the War Office, but at that time assistant-editor of the Globe, which was

then a Liberal journal:

“1st. That it was competent to the

Committee to enter into Mr. Thackeray’s complaints against Mr. Yates.

“2nd. That it is the opinion of

this Meeting that Mr. Thackeray’s complaints against Mr. Yates are well founded.

“3rd. That the practice of

publishing such articles, being reflections by one member of the Club against

any other, will be fatal to the comfort of the Club, and is intolerable in a

society of gentlemen.

“4th. That this Meeting is at once

prepared to support the Committee in any step they may consider necessary for

the suppression of this objectionable practice.

“5th. That this Meeting trusts that

a most disagreeable duty may be spared it by Mr. Yates making such ample apology

to Mr. Thackeray as may result in the withdrawal of all the unpleasant

expressions used in reference to this matter.

“6th. That with this expression of

opinion, the Meeting refers the whole question back to the Committee.”

The speakers who supported me at

the meeting were my friends Mr. Charles Dickens, Mr. Wilkie, Collins, Mr. Robert

Bell, Mr. Samuel Lover, Mr. Palgrave Simpson. These may have been influenced by

personal friendship; but there were other men of mark, with whom I had no kind

of acquaintance, but who were entirely actuated by a sense of justice in

defending my cause. Among them I may name the late Mr. Justice Willes and Sir

James Ferguson, now Governor of Bombay, then an officer in the Guards, who, on

reading of the case, was so struck with the bad feeling of the cabal against me

that he hurried home from Palestine, where he was travelling, to speak and vote

at the Garrick in my favour. But my enemies were too numerous and too powerful,

and on a division Mr. O’Dowd’s resolutions were carried by a majority of

twenty-four, the numbers being seventy and forty-six. (II 26-28)

…

The nineteen years’ seniority was

not reflected in the terms of our companionship or our converse. “Fancy my being

nineteen years older than this fellow!” said he one day to his eldest daughter,

putting his hand on my shoulder. The young lady promptly declared there was a

mistake somewhere, and that I was rather the elder of the two. And certainly,

except in the height of his domestic troubles, Dickens, until within a couple of

years of his death—when, even before he started for America, his health was, to

unprejudiced eyes, manifestly beginning to break—in bodily and mental vigour, in

buoyancy of spirits and keenness of appreciation, remained extraordinarily

young.

This, I think, is to be gleaned

from the Letters, but is not to be found in Forster’s Life. The

fact, I take it, is that the friendship between Dickens and Forster, as strong

on both sides in ’70 as it was in ’37, was yet of a different kind. Forster,

partly owing to natural temperament, partly to harassing official work and

ill-health, was almost as much over, as Dickens was under, their respective

actual years; and though Forster’s shrewd common sense, sound judgment, and deep

affection for his friend commanded, as was right, Dickens’s loving and grateful

acceptance of his views, and though the communion between them was never for a

moment weakened, it was not as a companion “in his lighter hour” that Dickens in

his latter days looked on Forster. Perhaps of all Dickens’s friends, the man in

whom he most recognised the ties of old friendship and pleasant companionship

existing to the last was Wilkie Collins; and of the warm-hearted hero-worship of

Charles Kent he had full appreciation. (II 92-93)

…

In the following week I accompanied

Dickens and his daughters, Wilkie Collins, Arthur Chappell, and Charles Kent to

Liverpool, whence he sailed next day in the Cuba, which, five years later, took

me to New York. Leave-taking, as is always the case, was difficult; we had

inspected Dickens’s cabin, looked round the ship, and were uncomfortably

uttering commonplaces, when the knot was cut by Dickens suddenly turning to me,

as standing nearest to him, and saying, “It must be done!”—then in his heartiest

tone, and with his warmest hand-grip, “God bless you, old fellow !” (II 113-114)

…

Some of the wittiest and most

amusing letters I have ever received came to me during my editorship of

Temple Bar from Miss BRADDON,

several of whose earlier attempts made their appearance under my

direction, and who has always honoured me with a steady friendship…

Hear her again as to the style in

which these same three-volume novels are very often written

“The Balzac-morbid-anatomy school

is my especial delight, but it seems you want the right-down sensational;

floppings at the end of chapters, and bits of paper hidden in secret drawers,

bank-notes and title-deeds under the carpet, and a part of the body putrefying

in the coal-scuttle. By the bye, what a splendid novel, a la Wilkie Collins, one

might write on a protracted search for the missing members of a murdered man,

dividing the arms not into books, but bits! ‘BIT

THE FIRST: The leg in the

gray stocking found at Deptford.’ ‘BIT

THE SECOND: The white hand

and the onyx ring with half an initial letter (unknown) and crest, skull with a

coronet, found in an Alpine crevasse!”

Seriously, though, you want a

sensational fiction to commence in January, you tell me. I cannot promise you

anything new, when, alas, I look round and find everything on this earth seems

to have been done, and done, and done again! Did not Jules Janin so complain

long ago in a protest against romancism, i.e. sensationalism? I will give the

kaleidoscope (which I cannot spell) another turn, and will do my very best with

the old bits of glass and pins and rubbish.

There they all are—the young lady

who has married a burglar, and who does not want to introduce him to her

friends; the duke (after the manner of ——) who comes into the world with

six-and-thirty pages of graphic detail, and goes out of it without having said ‘bo!’

to a goose; the two brothers who are perpetually taken for one another; the

twin-sisters ditto, ditto; the high-bred and conscientious banker, who has made

away with everybody’s title-deeds. Any novel combination of the well-known

figures is completely at your service, workmanship careful, delivery prompt.”

(II 171-173)

From Edmund Yates: His

Recollections and Experiences London 1884.

go back to biographies list

go back to Wilkie Collins front page

visit the Paul Lewis front page

All material on these pages is © Paul Lewis 1997-2007