1892

Story's Life of Linnell

|

|

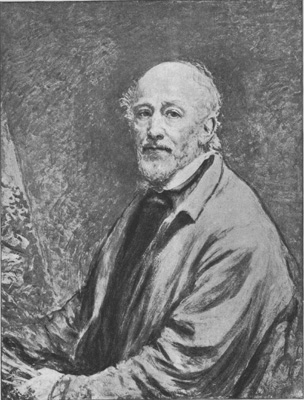

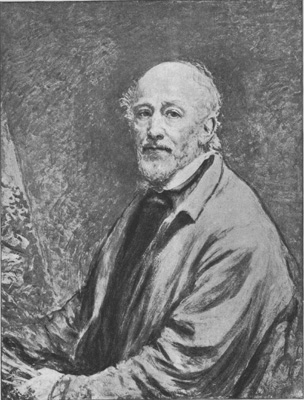

| John Linnell (1792-1882 seen above in self-portraits as a

young man and aged 76) was a little younger than Wilkie’s father William

Collins (1788-1847) but was also influenced by the work of George Morland

(1763-1804). Collins and Linnell were neighbours in Hampstead and later

lived a couple of doors apart in Porchester terrace, Bayswater. The Life

of John Linnell (1892) by Alfred T Story (1842-1934) contains some

anecdotes and letters of William Collins which give us an insight into the

religious belief’s of Wilkie’s father that would have been so much a part of

his early life as well as the closeness of the two families. There is a

description by Linnell of William Collins’s studio at 11 New Cavendish

Street where Wilkie was born. There is also a short anecdote about Wilkie

Collins as a boy as well as a brief mention of Linnell’s help with Wilkie’s

biography of his father. There is no evidence that Story met Wilkie Collins. |

[LINNELL HELPS WILLIAM COLLINS]

A few years later he was the cause of a scandal getting about respecting

William Collins similar to the one which did so much harm to Linnell. This

occurred when all three were living at Hampstead, and when they were often

travelling to and from town together by the coach. The scandal had reference to

a commission which Collins had received from Sir Robert Peel, and for which,

when finished, he had, according to Constable’s statement, overcharged him.

Meeting Linnell one day on the top of the Hampstead coach, Constable said:

‘Have you heard the story about Collins and Sir Robert Peel?’ and repeated the

scandal.

Linnell asked him if he had told Collins what was being said about him.

Constable said he had not, and that it was no business of his to do so.

A week or so later they met on the coach again, and Constable, returning to

the subject of the scandal, said

‘I fear it is a true bill against Collins.’

Linnell again asked him if he had got Collins’s version of the affair.

Constable said he had not, and repeated that it was no affair of his. Linnell

replied

‘I don’t believe a word of it, and if you won’t go and see Collins about it,

I will.’

They happened to be passing very near Collins’s house at the time, and

Linnell straightway got down from the coach and went and told him what Constable

had been saying respecting him. Collins was very indignant when he heard the

story, and said he believed that it was a pure invention, he himself having

heard nothing of the affair. It was decided, however, to put the matter into

Mulready’s hands to investigate, because he, on account of his high character,

was beyond suspicion. Mulready accordingly called upon Sir Robert Peel, and

asked him if there was any truth in the report. Sir Robert said there was none

whatever; he was perfectly satisfied with the pictures which he had commissioned

Mr. Collins to paint for him, and he had been charged no more for them than he

had agreed to pay.

All this is the more surprising on Constable’s part when it is seen on what

friendly terms the three artists nominally were. [I pp138-139]

[LINNELL SLIGHTED AND WILLIAM COLLINS INVOLVED]

Mr. Sheepshanks appears to have been a great oddity, with very little

independent judgment in regard to art, but very much imposed upon by titles.

Thus, on one occasion when Linnell called upon him for an amount that was due to

him for a picture, he was shown into an anteroom, where he heard the sound of

voices from an adjoining room, and the clatter of knives and forks. Mr.

Sheepshanks came in to him, and begged him to wait a minute or two while he

fetched the money, saying, I can’t take you in there’ (pointing to the room

whence the sounds came), ‘because I have got some R.A.’s at dinner.’

Amongst others, Linnell heard the voice of William Collins. He was, perhaps,

more sensitive than he need have been ; but he never forgot being considered

unworthy to be taken into the room in which some Academicians were dining. [I

p260]

[RELIGIOUS DIFFERENCES BETWEEN WILLIAM COLLINS AND LINNELL]

William Collins left Hampstead very soon after Linnell, and took a house

close to him in Porchester Terrace. His attachment to our artist appears to have

been very sincere, albeit he seems at times to have had some scruples about

associating with a man who was not only a Dissenter, but a ‘Sabbath-breaker,’ he

himself favouring the Puseyite form of faith-a form which Linnell satirized in

many a stinging line, as in the following

‘The monster lie exists at Rome,

Diluted it is seen at home

Priesthood set up, the Antichrist foretold,

Taking the place of Him who from of old

Was true High Priest, who coming did fulfil

All priestly types, and of his own free will

The sacrifice became for all, even the least,

And therefore no longer sacrifice, no longer priest.’

Collins called Linnell a Sabbath-breaker because he did not believe in our

English Sunday. The fact is, Linnell’s study of the Bible had led him the

conclusion that the observance of Sunday as the Sabbath was founded upon an

erroneous understanding of the Scriptures, and, in accordance with his usual

method, he did not allow himself to be bound by a religious ordinance that was

without Divine authority. Of his arguments in support of his contention more

will have to be said anon. Suffice it here to state that while he avoided giving

unnecessary offence to those who differed from him on this point, he did not

refrain from doing work on that day if he thought fit. Hence his neighbour’s

qualms.

One Sunday, in the warm spring weather, Collins happened to see Linnell

piously nailing his peach and nectarine trees against his northern wall, and was

greatly shocked. Not long after, when Dr. Liefchild, a famous Congregational

preacher of those days, was one day sitting for his portrait, Linnell sent for

Collins, thinking he would like to know the gentleman. Collins was pleased to

have the introduction; but during the conversation which ensued he took occasion

to denounce his brother-artist as a Sabbath-breaker. To his surprise, Liefchild,

though he held to a strict observance of the Sabbath, recognised Linnell’s

conscientious objections, and refrained from pronouncing the condemnation

Collins had doubtless looked for.

On another occasion Collins gave currency to a report that Linnell had

refused to pay one of his workmen, and wanted to cheat him out of his wages. The

calumny had reference to a man named Hobbs, whom the artist employed most of his

time in the garden, or doing other work about the place. In consequence of his

wife having on several occasions asked for and obtained his wages, and then

spent a large portion of the money in drink, Linnell refused to give the money

to her any more. She therefore went and maliciously told the Collinses that he

would not pay her husband’s wages, and Collins told the story to others. When

our artist heard what was being said, he took Hobbs to Collins, and asked him to

say in the latter’s presence if he had ever refused to pay him his wages.

‘No; you always paid me straight, like a gentleman,’ Hobbs replied.

‘Now, Mr. Collins,’ said Linnell, ‘I hope you will acknowledge your error in

circulating such an accusation without first ascertaining the truth of it.’

‘Of what consequence is it,’ Collins replied, ‘whether you cheated a man out

of his wages or not, when you are constantly doing things ten times worse?’

‘I suppose that is a hit at me for nailing up my nectarines on a Sunday

afternoon,’ said Linnell. Collins acknowledged that it was, and said that ‘a man

who would break the Sabbath would do any other bad thing.’

[RELATIONS OF COLLINS AND LINNELL FAMILIES]

The worthy Academician, though an amiable, was in many respects rather a

weak-minded, man. He appeared always to be oppressed by the twin bugbears

propriety and respectability, and found it difficult to forgive anyone who

failed in his respect to them.

Everyone has read the story of his meeting Blake in the Strand with a pot of

porter in his hand, and passing him without recognition. When he became an R.A.,

he felt that he greatly overtopped all who had not attained to that dignity, and

could not, therefore, legitimately write themselves down ‘Esquire,’ as the King

(to use his own words) had given him the title to do.

In this Collins reminds one of Uwins, who, when Linnell called on him about

the rejection of his picture ‘Noon,’ pointed to his Academy diploma, gorgeously

framed and glazed, over his chimneypiece, as though it were a patent of

infallibility.

These appear puerile matters; but they are, nevertheless, the sort of stuff

of which our life is largely composed. Nor are such weaknesses without their

kindly side. If men were equally strong all round, they might, perhaps, be less

amiable; and that Collins was of a good-natured and neighbourly disposition,

notwithstanding some narrowness, is proved by the fact that the friendship

betwixt him and Linnell never suffered any serious interruption, and that he was

frank, and even generous, in his acknowledgment of Linnell’s many kindnesses to

him.

The following letters show the kindly relations subsisting between the two

families. The first is dated from Hampstead, and the second, although undated,

evidently belongs to the period of the writer’s and Linnell’s residence at

Hampstead, because Blake, to whom it has reference, died whilst they were there.

‘Hampstead,

‘Thursday morning.

‘DEAR LINNELL,

‘I lose no time in writing to assure you that nothing but the distance

and a very severe illness which I had soon after my return from Holland have

prevented my calling upon you at Bayswater. No longer ago than last night I

heard (as I have frequently done before) from Mulready that you were going on

well.

‘With respect to your relative, I recollect giving him a letter to the

National Gallery in his real name, but I had nothing to do with his admission to

the Academy; but I will inquire about him when I go there again, and will let

you know the result when I have the pleasure of seeing you, which I sincerely

hope I shall be able to accomplish as soon as a cold which I am now nursing will

allow me.

‘Mrs. Collins wishes very much to call upon Mrs. Linnell, and it is not

impossible that we may visit you together. She and the children are, thank God,

very well, but my mother is still in a melancholy way.

‘With our kindest regards to Mrs. Linnell, yourself, and family,

‘Believe me,

‘Most faithfully yours,

‘WILLIAM COLLINS.’

‘Monday morning,

‘11 New Cavendish Street.’*

‘DEAR LINNELL

‘

If Mr. Blake will send a receipt to Mr. Smirke, junior, Stratford Place,

he will be paid. It is not necessary that Mr. B. should make a formal

application.

‘Yours faithfully,

‘WILLIAM COLLINS.

‘Let me know the result.’

* Mr. Collins’s studio was in New Cavendish Street.

The next letter probably belongs to the same or a little later period

‘Thursday night.

‘DEAR LINNELL,

‘Will it suit your convenience to go with me on Saturday next at

half-past one to see the collection of German pictures in Euston Square?

‘Yours truly,

‘W. COLLINS.

‘I have written to Mulready to request he will call here at the hour

above mentioned.’

Fortunately the two following interesting letters, written from North Wales,

are dated

‘Llanberis, N. W.,

‘August 11,1834.

‘DEAR LINNELL,

‘I have just received yours containing the halves of a £10 and £5 note.

At your earliest convenience send me the remainder by the same mode of

conveyance, with any other letters which may have been received since. When you

happen to go into the City—pray do not go on purpose—be kind enough to call upon

Mr. Searle at Messrs. George Wildes and Searle (19, I think), Coleman Street,

and show him the annexed letter, as well as this part of mine, as your authority

to receive the amount there mentioned, which keep for me until my return. Do not

leave Mr. Lee’s letter with him unless he insists upon it, as I wish to keep it.

As yet I do not feel much benefited by my journey—my spirits still flag much;

but all is for the best, as I feel greatly humbled.

‘With regards to Mrs. Linnell and all friends, ‘Yours truly,

‘W. COLLINS.

‘How are the Richmonds?

‘I thank you for your offer of touching upon the picture by Finden, and accept

it. Let me know what is the subject of it.

‘Mrs. Collins desires the remainder of this scrap, so farewell. When you see

Wilkie, tell him I wish much to know how he is, and give him my regards. I hope

to find time to write to him soon.’

‘I thank you, my dear friend, for your kind note, and the information it

contains. I wish you could see our present place of residence-surrounded by such

mountains and rocks; but I have not lost my cat-like propensity of loving home.

There are troubles and difficulties everywhere. Lucy has been very ill since we

have been here, and no servant is kept by our landlady, who has a young child

and a shop to mind. I leave you to judge of the attendance under these

circumstances.

It is quite a foreign country; no one understands us, nor can we comprehend

their jargon. Milk is scarce-eggs the same; bread very doubtful to get, unless

you send seven miles to Carnarvon. Meat only to be had there. Lean ducks and

chickens brought alive for us to get killed and picked; no fruit; good

potatoes—no other vegetable. The scenery is truly grand, but of the wild, savage

kind. Mr. Collins went to the top of Snowdon Friday with the Bells, who came

here on their way home. We have the only lodging in the place; but there are two

good inns.

‘I think I am nearly the same as usual in health. Willy quite well; Charlie

thinner, and has been poorly, but is again picking up. I have never heard from

my sister. I think the letter she talked of writing must be lost. Perhaps Anny

would write for me a few lines to her to say that I fear she has written, and

the letter miscarried, and that if she sends to you it will be forwarded.

‘How shall we ever make you amends for all you have done and are doing for

us?

‘We shall proceed on our travels on Saturday; but Mr. Bransby will still be

our agent. We are going through Beddgelert, Dolgelly, etc., to Barmouth, where I

hope we shall be stationary.

‘Farewell. Love to Anny, Lizzie, etc., and believe me,

‘Most affectionately yours,

‘W. COLLINS.’

‘Beddgelert, North Wales,

‘August 18, 1834.

‘DEAR LINNELL,

‘I have this morning seen a gentleman from Birmingham, who seems to think

the present season most favourable for their exhibition, as the great music

meeting and other local attractions will draw much company to the town. This

circumstance, and his request that I should send them a picture, has brought to

my recollection what you advised in one of your recent letters, and I have

decided upon sending the " Haunts of the Seafowl." You were good enough to offer

your services should I feel disposed to send them anything, and I beg to accept

them. I hope, too, you will embrace the favourable opportunity, and let them

have a picture or two of your own.

‘The picture has been carefully hung up, and if you can spare time, perhaps

you will be present when it is taken down, and, as it is very heavy, give a

caution to those who undertake to pack it for Birmingham. I have this evening

written to the secretary, Mr. Wyatt, but it will be proper that you should send

a letter describing the picture as above, and stating that it is for sale at the

price of three hundred guineas, including the frame.

‘We are all pretty well, and delighting in the scenery of this neighbourhood,

and purpose going on to Barmouth in a few days. Carnarvon, as before, will be

the best address, as Mr. Bransby will forward all communications. I had hoped to

receive the other halves of the notes this morning; I trust, however, soon to

get them.

‘Harriet unites with me in kindest remembrances to Mrs. Linnell and the

family, as well as to all friends.

‘Very faithfully yours,

‘WILLIAM COLLINS.

* * * * * * * * * * * *

‘Did you receive a letter containing an order on Mr. Searle, of the house of

George Wildes and Searle, 19, Coleman Street, for £9 odd?’

[WILLIAM COLLINS’S STUDIO AT NEW CAVENDISH STREET]

Soon after the date of the last letter—that is, in 1835—Mr. Alaric A. Watts

wrote to John Linnell, asking if he could help him ‘with a few anecdotes of our

excellent friend W. Collins, to relieve the baldness of mere dates’ in an

article he was writing about the Royal Academy to accompany a print of his

picture of ‘The Gate,’ and suggesting that a little criticism and description of

some of his pictures would be acceptable. In reply Linnell wrote as follows

‘DEAR SIR,

‘ I am sorry that I find it difficult to remember anything respecting our

friend Collins which would be useful to you, especially when I confine myself

within the, limits consistent with my intimacy with him. I think it best,

therefore, to mention only those facts which his modesty and goodness would

prevent your obtaining from himself, such, for instance, as his supporting his

mother entirely to the day of her death, and partly his brother. His father, who

dealt in pictures, kept a small shop in Great Portland Street, and died, without

leaving any property, when Collins was not more, I believe, than about twenty

years of age. But he improved so rapidly as soon to be enabled to take a house

in New Cavendish Street, where some of his best pictures were painted—"The Sale

of Fish by Dropping a Stone" was one, I remember. From there he removed to

Hampstead, where he painted his "Frost Piece," and companion, for Sir Robert

Peel. His early success, however, was in a great measure owing to his patronage

by Lord Liverpool.

‘Collins’s painting-room at Cavendish Street was an interesting atelier,

and was made by simply inserting a skylight into the roof of the attic floor and

removing some partitions. The sloping ceiling, with the screens covered with

beautiful sketches on millboard without frames, and arranged only for the

purposes of study, the lay figure draped, etc., with a fireplace like that of an

alchemist, small and convenient for experiments, some of which were generally

going on for perfecting varnishes and oils, altogether made a most picturesque

retreat, which was visited by many great personages, who were sometimes candid

enough to confess there was a charm about a place arranged for the purposes of

art which surpassed all the splendours of their impracticable

saloons. There was a kind of monastic seclusion and security about

this nest of art which at once delighted and humbled the mind of the visitor,

producing a love of art without ostentation.

Of Collins’s style and painting in general, it may be said that, though there

may be some artists who are more intensely admired by a few, there is no one who

has more admirers, and few so many.’

[WILKIE COLLINS AS A BOY ON LINNELL]

A characteristic anecdote relating to the intimacy existing between the two

families is told by the sons of the painter. Young Wilkie Collins, who was their

playmate at Bayswater, was one day in the garden with them, when they happened

to draw upon themselves the wrath of their father. Said young Wilkie when the

passing storm was over

‘I should not like your father to be mine. Your father is a bull; mine is a

cow.’ Not a bad bit of characterization for one who was afterwards to become a

famous novelist.

Constable was even less tolerant of Linnell’s dissent than Collins. He used

to say that all Dissenters had heads no better than shoemakers, to which Linnell

retorted that Constable’s own head was like a shoemaker’s, being long and flat.

[I pp276-287]

[WILKIE COLLINS ASKS LINNELL’S HELP WITH FATHER’S LIFE]

In 1847 Linnell’s old friend, William Collins, died, and he was some little

time afterwards asked to assist Wilkie Collins in the compilation of a life of

his father. Incidentally the matter is referred to in the following letter,

addressed to Mrs. Linnell, which, unfortunately, has no date

MY DEAR MRS. LINNELL,

‘My brother and I are very anxious to take advantage of your kind

invitation to us to pay you a visit at Porchester Terrace some evening.I now

write to know whether to-morrow or Friday evening will be convenient to you. We

are disengaged on either day.

‘ I shall hope to find Mr. Linnell at home, as I hear he has some hints to

give me respecting the early parts of my father’s life, which will, I am sure,

be of very great use to me in the biography I am now writing.

‘ Do not trouble yourself to write.A verbal answer by the bearer, either for

to-morrow or Friday evening, will be quite sufficient.

‘Truly yours,

‘W. WILKIE COLLINS.

‘Tuesday evening.’

The brother referred to, of course, was Charles Collins, who, following in

his father’s footsteps, became an artist. Linnell gave Wilkie Collins all the

aid he could in respect to the biography, and the author was recognisant to the

extent of referring to him in its pages as being so capable an artist as to be

able to arrange a row of blacking-bottles in such a way that they would look

picturesque. [II pp24-25]

From The Life of John Linnell by Alfred T. Story (1842-1834) 2 vols,

Richard Bentley and Son, London 1892.

go back to biographies list

go back to Wilkie Collins front page

visit the Paul Lewis front page

All material on these pages is © Paul Lewis 1997-2006