1891

From Life

|

|

|

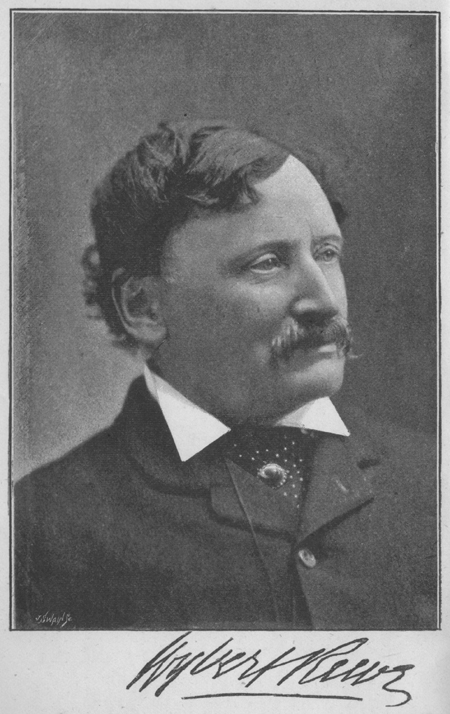

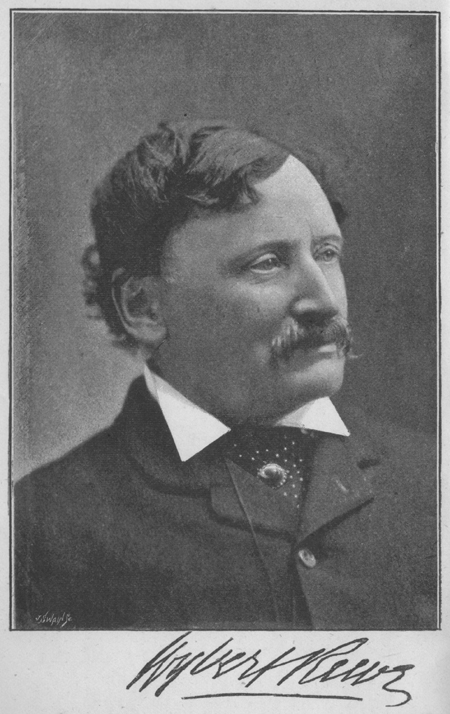

Actor manager Wybert Reeve (1830-1906) became

friendly with Collins in 1871 when he played in The Woman in White

and then took it on tour. He also dramatised No Name. Reeve's account contains interesting anecdotes

about Wilkie's appearance and health, Dickens - including an important story

about his relationship with his wife - John Forster, Charles Reade, the production of

The Woman in White, Man and Wife and The New Magdalen,

and anecdotes of his time in America. It also contains extracts of letters

and is the only source for most known letters to Reeve. The text is taken

from Reeve's book From Life published in Australia in 1891 but first

appeared slightly earlier in The Australasian.

Many parts of these

recollections were repeated by Reeve in a shorter version in Chamber's

Journal in 1906. He cut most

of the account of The Woman in White and extracts from three letters.

The book is badly sub-edited.

It has ‘Foster’ for ‘Forster’ throughout; ‘Hartright’ is misspelt

‘Heartright’ and Régnier as ‘Reginer’. There are misplaced quotation marks,

and one reference to Wilkie where the word ‘actors’ should almost certainly

be ‘authors’. These are marked [sic] in this text. A couple of

misplaced quotation marks have been corrected without a note. |

PERSONAL RECOLLECTIONS OF WILKIE

COLLINS.

I

HAD

played John Mildmay during a short revival of Still Waters Run Deep, at

the Lyceum Theatre, London, and for six months in two of my own comedies at the

Charing Cross, now Toole’s Theatre, and had gone back into the country, when I

received a telegram from London proposing the part of Walter Heartright [sic]

for me, in a new play to be produced at the Olympic Theatre, by Wilkie Collins,

The Woman in White. I accepted the proposal, and attended the first

reading of the drama by Mr. George Vining, who was cast for Count Fosco. It

lasted over two hours and a half, but the play, though long, struck me as being

clever, original, and effective. The rehearsals commenced the next day, and the

second morning Mr. Wilkie Collins attended—a short, moderately thick-set man,

with beard, moustache, and whiskers slightly tinged with white; a bent figure,

caused by suffering; a full, massive, very clever head and forehead; and bright,

intellectual eyes, looking out of strong eye-glasses mounted in gold. He asked

to be introduced to me, and an acquaintance then commenced which ripened into

strong friendship, only ending with his death.

They were terrible rehearsals,

tiresome in the extreme, from ten o’clock in the morning until five o’clock in

the afternoon—sometimes from six or seven o’clock in the evening to one and two

o’clock in the morning. Endless arguments arose about crossing the stage, the

position of the several characters, of a chair, a sofa, or a table. The two

ladies—the one playing Anne Catherick and doubling Lady Glyde, the other Marion

Halcombe—had a little difference of opinion. Neither liked to give way to the

other. On a question of whether both could not keep their faces to the audience

at the same time during the recognition scene in the Lunatic Asylum the

discussion lasted over an hour on one occasion. Mr. Vining should at once have

directed the business and insisted on it, but he was a bad stage-manager. Wilkie

Collins looked “perplexed in the extreme,” not knowing which side to take, but

he was gentlemanly, patient, and good-tempered, always ready for a smile if a

chance offered itself, or a peaceful word, kindly suggesting something when a

point was to be gained. I marvelled at him, for authors as a rule are the

reverse of patient when their own pieces are rehearsing. They naturally form

their own conception of characters they have created, and object to have their

ideas differently interpreted by the actor or actress. The difficulties were got

through, and the 9th of October was the eventful night of the production of the

play. It was a great success. At the end of the third act there was a loud call

for the author, and Collins, after a good deal of trouble, was induced to appear

before the curtain and respond to it. He was suffering a good deal from nervous

anxiety. To my surprise the two ladies were waiting for him at the wing, each

anxious to be taken on, and to allow the other no advantage. He was wise, no

doubt; although the call was his, he marched them both on before the curtain.

The newspapers pronounced it the

best drama, and the most interesting one written of late years, and likely to be

the forerunner of a new and better school. There was a divided opinion as to the

merit of Mr. Vining’s Count Fosco, at which he was greatly enraged, and

foolishly advertised both the good and bad notices side by side, calling

attention in a rather egotistical, unwise, and certainly offensive manner to the

opposite opinion of the critics. It did both the piece and his acting far more

harm than good. “Wise men know well enough” it’s no use fighting with the press.

Before the piece had played a fortnight I was exceedingly surprised by the

management asking me to be studied in the part of “Fosco.” There were some

doubts with regard to Mr. Vining, it was necessary to be prepared, and Mr.

Collins had said either I must play the part, should anything occur, or Mr.

Fechter must be engaged. The latter was an impossibility, so there was nothing

for it but for me to set to work. It was not until January 11th Mr. Vining

suddenly broke down from cold and a bad throat, and at a day’s notice I had to

go on, fortunately for me with a very satisfactory result. On the 24th of

February the piece was withdrawn, and Mr. Vining immediately started with a

company for the provinces. I followed with another. This brought me into more

intimate relations with Wilkie Collins during the years that succeeded, and I

continued playing the part. Nothing could exceed his friendly consideration, or

the pleasure of our business transactions.

Mr. Vining failing of success in

the provinces in a few weeks, and not having behaved well in the transaction

with me, Mr. Collins destroyed the agreement between them, took all future right

in the piece from him, and placed it in my hands, for all future performances.

Nothing could be more generous than his acknowledgments to me. In June 1873, he

writes:

“MY DEAR REEVE,—First let me

heartily congratulate you on the great increase of reputation which your

performance of Fosco has so worthily won. I and my play are both deeply indebted

to your artistic sympathy, and your admirable business management—to say nothing

of the great increase of sale in the book in each town you play, &c.”

Later on, I wished to make a

difference in our arrangements, more to his advantage. He replies:

“I cannot reconcile myself to the

idea. You, who have assumed the responsibility, surely ought to be the first

gainer. I thank you most heartily, but pray forgive me if I ask you, for my

sake, to say no more about it.”

I quote these letters, not out of

any vain consideration for myself, but because they speak volumes as to the

generosity and kindness of his nature, and I cannot help sometimes drawing a

comparison between Mr. Collins and some of the leading authors of the present

day in the extravagant demands they make, often to the serious loss of the

speculator, manager, or actor, as the case may be.

When in London we invariably

arranged to dine together at his house in Gloucester-place, and spend a quiet

evening afterwards. During these pleasant meetings we chatted over many men and

things.

Of Charles Dickens he always spoke

in terms of the strongest affection; they had been friends for many years. He

described to me the meetings, when the idea of Dickens reading his own works was

first proposed. Collins was greatly in favour of his doing it. Other friends

thought it infra dig, and objected. As all the world knows, the good

advice prevailed. I say good advice, because thousands of people rejoiced in

listening to his marvellous power of individualizing his own characters at the

reading-desk; but that the continued exertion shortened his life is certain.

Before any new reading he invited Collins and a few others to dinner, and in the

evening rehearsed it for their opinion and advice. Collins said he could never

forget the Nancy and Bill Sikes scenes—the effect of it upon Dickens was

wonderful and painful in the extreme—every nerve in his sensitive temperament

was wound up to such a pitch of excited energy that he fainted, and always

afterwards when he read the scenes in public they exhausted him. He was strongly

advised not to continue, but, seeing the effect they had upon the public, he

persevered. “This reading,” said Collins, “did more to kill him than all his

other work put together.” Of John Foster’s [sic] life, he had little that

was good to say. He and other friends of the dead author were most desirous of

suppressing many things in the book, which might have been omitted with no loss

to the public. Every great man has little weaknesses. One of Charles Dickens’s

was vanity. Why parade it? Why tell of family matters with which the public have

nothing to do? Foster was not to be advised or controlled. Foster’s own vanity

and identity with all Dickens’s works and actions are so persistently put before

the reader that John Foster is as prominent as Charles Dickens throughout.

With regard to the unfortunate

disagreements between Dickens and his wife, there is little doubt she was

unsuited to a sensitive, quick-tempered nature. She was entirely wanting in

tact. Collins described to me a scene at Judge Talfourd’s. It was a dinner

party, at which most of the leading representatives of literature and art were

present. The conversation turned on Dickens’s last book. Some of the characters

were highly praised. Mrs. Dickens joined in the conversation, and said she could

not understand what people could see in his writings to talk so much about them.

The face of Dickens betrayed his feelings. Again the book was referred to, and a

lady present said she wondered when and how many strange thoughts came into his

head. “Oh,” replied Dickens, “I don’t know. They come at odd times, sometimes in

the night, when I jump out of bed, and dot them down, for fear I should have

lost them by the morning.” “That is true,” said Mrs. Dickens. “I have reason to

know it, jumping out of bed, and getting in again, with his feet as cold as a

stone.” Dickens left the table, and was afterwards found sitting alone in a

small room off the hall—silent and angry. It was a long time before they could

induce him to join the circle again. We talked over many things in Foster’s life

of his dead friend, and some of them he directly contradicted. We talked over

other matters concerning Dickens not in the book, and the impression left upon

me was that there was much beauty in the character of Charles Dickens. Collins

was too just to be partial; he knew his friend’s failings, and spoke of them.

Unfortunately, I only met Charles Dickens twice—and then it was in the company

of others. I only remember his expressive face, so strongly marked, so full of

character, and his persuasive voice. Another friend of both authors stands out

clearly though, as Wilkie Collins and I entered his room on my first visit—a

big, burly, carelessly-dressed man, with loosely-cut clothes on, a fine head,

good features, rather long, straggling, uncut hair—Charles Reade. He was cutting

the pictures out of various periodicals, and sticking them in a large book open

before him. Discarded Illustrated News and Graphics littered the

floor thickly about him. The study was exactly as described in A Terrible

Temptation. As we entered, he looked up with a genial smile, shook hands,

then thrust both hands deep down in his pockets, and walking to the fire turned

his back to it. His language was strong, but his heart was as tender as a

child’s, with almost a child’s vanity. “You will see,” said a lady to me, “how I

will please him.” “Oh, Mr. Reade,” she said, looking at him. “I like looking at

you, there is something in your face so good, and so manly.” “ My dear Mrs.—,”

replied Reade, “you flatter me. Upon my life, I should be angry, if I did not

know you were a woman of judgment,” and the next minute he turned to the glass,

brushing up his hair with his hands, as pleased as possible, seeking out the

particular points in his face on which she founded her opinion. He was eccentric

in some things. His great ambition was to be a theatrical manager, and he was

never better pleased than when rehearsing some of his pieces. He was a great

stickler for reality. On producing a play at the Princess’s, the first act of

which was a farmyard scene, he insisted on having a real stone wall built the

stones all a certain size. It was an immense amount of trouble, and did not look

half so effective as a painted one. Amongst other things he insisted on having a

live pig on the stage; the property-master raising some objection, Reade lost

his temper, drove to the market and bought one. He was bringing it back in

triumph to the stage-door, when arriving there, an officious super, seeing who

it was, quickly opened the door of the cab, which Reade was unprepared for; out

jumped the pig, and away it scampered down the street, Reade after it, calling

out, “Stop my pig,” to the amusement and surprise of all the young ruffianism of

the neighbourhood. Collins delighted in telling this story, and in imitating

Reade and his pig-hunt.

He was often amused, sometimes

angry, at the opinions written, and expressed, as to the improbability and

extravagance of his characters and plots. “I wish,” he once said to me, “before

people make such assertions they would think what they are talking or writing

about. I know of very few instances in which fiction exceeds the probability of

reality. With regard to my novels, I’ll tell you where I got many of my plots

from. I was in Paris, wandering about the streets and amusing myself by looking

into the shops. I came to an old book place—half shop and half store, and I

found some dilapidated volumes, the records of French crime—a sort of French

Newgate Calendar. I thought, here is a prize. So it turned out to be. In them I

found some of my best plots.

The Woman in White

was one. The plot of that has been

called outrageous—the substitution and burial of the mad girl for Lady Glyde,

and the incarceration of Lady Glyde as the mad girl. It was true, and it was

from the trial of the villain of the plot—the Count Fosco of the novel—I got my

story.”

In Man and Wife he protested

against men overtraining, and in August 1882, he writes me—“I am getting on with

a new story. I am striking a blow in my new story at the wretches who are called

vivisectors.” In writing to me on the production of the former play at the

Prince of Wales’s Theatre, he says:— “It was certainly an extraordinary success.

The pit got on its legs and cheered with all its might the moment I showed

myself in front of the curtain. I had only thirty friends in the house to match

against a packed band of the ‘lower orders’ of literature and the drama,

assembled at the back of the dress circle, to hiss and laugh at the first

chance. The services of my friends were not required. The public never gave the

‘opposition’. a chance all through the evening. The acting was really superb—the

Bancrofts, Miss Foote, Hare, Coglan, surpassed themselves—not a mistake made by

anybody. The play was over at a quarter past eleven sharp. It remains to be seen

whether I can fill the theatre with a new audience. Thus far, the results have

been extraordinary.” He then quotes to me the receipts, and later on they

average over £100 a night. On one occasion, he writes:— “They actually

accommodated £131 in that little place.[”] I was up in London during the run,

and he arranged for a box, that we might go together. On arriving at his house

to dinner, I found him in very low spirits. His brother was very ill, probably

dying, and he was unable to go with me. He had a friend staying in the house,

and we went together. I had promised to return to supper, and tell him what I

thought of the play and the performance. When I got back his brother was dead.

He had just returned terribly broken down about it. We talked together until

nearly two o’clock in the morning.

On finishing the dramatization of

the New Magdalen, he writes me:— “Both Miss Cavendish and I would be glad

to obtain your valuable assistance to direct the performances, and to play the

principal part.” My having decided on visiting America, and other business

matters prevented this arrangement. After its production he writes me:— “The

reception of my New Magdalen was prodigious. I was forced to appear

half-way though the piece, as well as at the end, The acting took every one by

surprise, and the second night’s enthusiasm quite equalled the first.” “We have

really hit the mark,” later on he writes me. “Ferrari translates it for Italy,

Reginer [sic] has two theatres ready for me in Paris, and Lambe, of

Vienna, has accepted it for his theatre. Here the enthusiasm continues.”

On March 10th, 1873, he says in a

letter:— “I have had a great offer to go to America this autumn and ‘read.’ It

would be very pleasant, and I should like it if we could go together. I am

really thinking of the trip.”

The trip was decided on, and it was

arranged that we should start together as he desired, but circumstances

prevented my leaving England within two or three weeks of the date. So I

followed him a few weeks after. Before starting a circumstance occurred in

Scarborough perhaps worth relating, showing how small a world it is with some

people. A friend of mine, a doctor, was visiting one evening a patient of his, a

large cotton-spinner from one of the Lancashire towns, and asked me to go with

him. Two Manchester merchants, who had just returned from the exhibition at

Vienna, friends of the patient’s, were there. It was the first time the

Manchester men had been on the Continent, and they were comparing the places

they had seen to Manchester, returning with the full conviction that there was

not a place to compare with it. Tall chimneys, manufactories, and huge

warehouses, formed, in their eyes, the acme of all that was necessary to

beautify the world.

“So, Mr. Reeve,” said the patient,

“the doctor tells me you are just off to America?”

“Yes, in a few weeks’ time,” I replied. “Going by yourself?

“No; with a friend.”

“Mr. Reeve is going with Mr. Wilkie Collins,” said the doctor.

“Oh, indeed,” replied the gentleman, and the name was passed round by the three

merchants.

“Collins,” said one, thinking; “Wilkie Collins,” said the other, evidently

trying to recall the name.

“Never heard of him,” said the patient. “Nor I.” “ Nor I,” the others replied.

“Mr. Reeve,” asked one of the gentlemen, “Wilkie Collins, what Manchester house

does he represent?”

I joined Collins at the Westminster

Hotel in New York, and found him comfortably settled in the same sitting-room

and bedroom his friend Charles Dickens had lived in. Every one knows the extent

to which interviewing is carried on in America, where every paper has its

interviewer, generally a man not troubled with modesty, or wanting push

sufficient to force himself into every bedroom, if he cannot get his information

otherwise. Of course Collins was interviewed. It was the pest of his life for

the first two or three weeks. One thing greatly amused us. Before leaving

England he found himself in want of a rough cheap suit of clothes to wear

travelling, and driving through the city he turned into Moses’s great emporium

and bought a cheap shoddy suit.

The New York Herald, in

describing Collins, gave an elaborate account of his person. He was wearing at

the time the slop suit, and the description wound up with the statement that Mr.

Collins was evidently a connoisseur in dress. He had on one of those stylish

West End tailor’s suits of a fashionable cut, by which an Englishman of taste is

known. A circumstance occurred in New York which is a very good illustration of

what housekeepers have to put up with in servants in that part of the world.

We were invited out to dinner to a

large stone house in Fifth-avenue on a Sunday. Arriving there we were received

by the host and hostess; they both seemed to be very uncomfortable, and I had

noticed that a young lady opened the front door to us. At length the hostess

asked us to excuse the want of servants, and the dinner, which consisted of a

piece of cold meat, some fruit and cheese. She explained that the servants

objected to guests in the house on Sunday, as they wished to have that day to

themselves. They had been humbly asked by their mistress to permit it on this

occasion; they graciously acknowledged they might have done so if they had had a

week’s notice to alter their arrangements, but as it was only a day’s, it was

quite out of the question; and accordingly they had walked out of the house. We

have not quite arrived at this pass yet in Australia, but it is only a question

of time.

Another rather amusing circumstance

occurred. He arrived in an up-country town in the afternoon to give a reading in

the evening, and was washing himself after a long railway journey, in his

bedroom, when a servant in the hotel opened the door without knocking, and

asked—

“ Are you the Britisher as is come

down ’ere to do a bit o’ reading?”

“Yes, I suppose I am the man.

“Well, ’ere’s some o’ the big bugs

and bosses o’ this ’ere town come jist to see you.”

The chief men in the town had come

to pay their respects and welcome him.

“That’s awkward,” replied Collins;

“I am just dressing.” “I guess they’ll wait till you’ve scrubbed your skin and

put on your pants. Jist say when you’re ready.”

With that he coolly walked to the

window, opened it; it was a very cold day, and leaning out, commenced leisurely

spitting into the yard below. He was chewing tobacco.

“My friend,” said Collins, “when

you have done spitting, would you mind closing that window?”

“Well, I don’t see the harm it’s

a-doing you.”

“Perhaps not, but if you will shut

it, and tell the gentlemen below I will be with them directly, it will do me

more good.”

“You’d better tell them yerself, I

guess. If you objects to my spitting out o’ this winder, I objects to yer trying

to boss this establishment.”

And putting his hands in his

pockets, he leisurely lounged out of the room, and left Wilkie Collins standing

in amazement at the fellow’s impudence.

His readings were not as successful

as he anticipated. I was not surprised at this. I never had an opportunity of

hearing him; but I am quite sure be lacked the necessary power to make them

acceptable to a general audience.

As a further proof of his

good-nature, I may mention that, in America especially, I found it absolutely

necessary to cut out several of the dialogue scenes, possessing neither action

or interest, in the last acts of The Woman in White. They served

certainly to unravel and carry on the plot in a way that was well enough in a

novel, but tedious on the stage. One scene particularly between Sir Percival and

his servant, which consisted of letters and telegrams chiefly, wanted omitting.

He could not see how it was possible to carry on the plot without it; we had

several talks, and letters passed on the subject. Finally, he agreed to leave

the matter in my hands, which ended in my condensing all the necessary matter of

the three scenes in the one act of the asylum, and making it really, as the

piece was afterwards noticed, the most powerful in the play.

He had dramatized No Name,

and, in wishing to provide me with another character than Fosco, suggested

Captain Wragge. He was most dissatisfied with his work, and asked me if I would

write another play, and then we would compare the two. I did so. The only fault

he found was I had in the last act kept too closely to his novel, which I had of

course done purposely, not to hurt his pride in his work. To my surprise he gave

me a carte blanche to do as I liked with the characters. The result

pleased him, and he never allowed his own version to be played afterwards; mine

was the only one since acted. Very few actors [sic] —in fact I cannot

name one—would have done the same.

His health was continually bad; his

letters always refer to it. “I am only just recovering from a severe attack of

gout in the eyes.” “I am away in France so as to get the completest possible

change of air and scene. God knows I want it.” Another time he is in Venice,

trying to shake off this continuous suffering, or “I am cruising in the Channel,

and getting back my strength after a long attack.” From my first knowledge of

him in 1871 he had been in the habit of taking opium in considerable doses, and

had frequent injections of morphia to relieve the neuralgic pains he suffered

from besides gout.

His diet was singular. At dinner he

would sometimes take some bread soaked in meat-gravy only. In the night he was

fond of cold soup and champagne. For exercise he often walked quickly up and

down-stairs so many times by the aid of the bannisters. And I am quite certain

the frequent use of opium had its effect upon his writing in later years.

At Christmas, 1883, 1 received a

Christmas card from him, a picture of English oaks, on which he had written “A

little bit of English landscape, my dear Reeve, to remind you of the old

country, and the old friend.” His idea of Australia was a somewhat strange one;

he had little notion of oaks ever growing there, or of intellectuality and

refinement being found among its native born inhabitants. He thought, as many do

in England, that Australians were a hardy, rough race, and that huge deserts or

wildernesses were the only characteristics of the country.

In 1886, he writes me:— “My new

novel, now shortly to be published in book form, has appeared previously in

various newspapers, and the speculator purchasing all serial rights in England

and the colonies, has given me the largest sum I have ever received for any of

my books before.”

I cannot better close these random

memories of one whose friendship I valued and whose death I lament than by

quoting the last words of this letter.

“As for my health, considering that

I was sixty-two years old last birthday, that I have worked hard as a writer

(perhaps few literary men harder), and that gout has tried to blind me first and

kill me afterwards on more than one occasion, I must not complain. Neuralgia and

nervous exhaustion generally have sent me to the sea to be patched up, and the

sea is justifying my confidence in it. I must try, old friend, and live long

enough to welcome you back when you return to be with us once more.

“Always truly yours,

“WILKIE COLLINS.”

From

Wybert Reeve From

Life George Robertson

and Company, 1891. It originally appeared in the Melbourne newspaper The

Australasian.

go back to biographies list

go back to Wilkie Collins front page

visit the Paul Lewis front page

All material on these pages is © Paul Lewis 1997-2007