|

|

| William Holman Hunt (1827-1910) knew Wilkie Collins through his brother Charles, who was close to Hunt and Millais and a candidate – ultimately rejected – for membership of their Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood. Hunt’s two volume Pre-Raphaelitism and the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood (1905) is a chronological autobiography in which Wilkie, Charles and even their mother Harriet turn up. These extracts include all those passages starting with Wilkie, then Harriet, then Charles - which is illustrated with pictures by Charles and Hunt. Hunt is seen above in a caricature by Spy (Leslie Ward) in Vanity Fair 19 July 1879. |

[WILKIE COLLINS ON HIS BROTHER CHARLES]

VOL I CHAPTER XI 1851

…This visit to town only occupied me a day, and I lost no time

in resuming work to finish all the details in my background. Gabriel Rossetti

had not been to see us, although once or twice we had expected him. William

Millais came and stayed, painting a small landscape, and Wilkie Collins also

came to see us. In youth he had thought of being a painter, but had gradually

drifted into literature. He was a man now, slight of build, about five feet six

inches in height, with an impressive head, the cranium being noticeably more

prominent on the right side than on the left, which inequality did not amount to

a disfigurement; perhaps indeed it gave a stronger impression of intellectual

power. He was redundant in pleasant temperament, his immediate concern was in

his brother’s recent inclination to extreme Church discipline and rigorous

self-denial in matters of fasting and calendar observances, which in Wilkie’s

mind could only be prejudicial to health and to the due exercise of his ability.

He charged us not to be too persistent in our comments upon the eccentricity,

believing that, if left alone, Charley would not long persevere in his new

course. Wilkie took a lively interest in our pursuits, and professed a desire to

write an article on our method of work, leaving the question of the value of

results entirely apart, that the public might understand our earnestness in the

direct pursuit of nature, which, if not establishing the excellence of our

productions, would at least be convincing proof that our untiring ambition was

not to copy any mediaevalists, as it was so generally said we did, but to be

persistent rather in the pursuit of new truth. This intention was never acted

upon. [I 302-4]

[WILKIE COLLINS ON ART]

VOL I CHAPTER XII 1852

…As a pleasant and cheering distraction I occasionally dined

with the Collins family. Nothing could well exceed the jollity of these little

dinners. Edward Ward and his pleasant wife would sometimes be of the party. In

any case Mrs. Collins did not often make our smoking after the meal a reason for

her absence from our company. We were all hard-worked people enjoying one

another’s society, and we talked as only such can. Many of the stories that were

told were of artists and authors of the last generation. Verily a man has not

played his full part when he is buried. While yet his contemporaries old or

young have tongues wherewith to re-echo and reanimate his unforgettable

personality, he is still often called upon to come forth and repeat his role.

David Wilkie, with his simplicity, his absent mindedness, and his strong Scotch

accent; Turner, with his unpolished exterior and his direct and piquant speech;

Constable, with his contempt for the sophistication of Nature, and, besides

these, others who had been of mark only for a passing season, not infrequently

came before us. Bailey the sculptor, to wit, was a man who took an ephemeral

success as one betokening unending glory for himself, and on the strength of

this prospect drove about in handsome equipages until one day he discovered that

the summer warmth on his brilliant wings had gone by for ever. The view of

Morland lying brutally unconscious in drink was revealed to us; his was an

eternity, not of innocent yet unrealised joy, but of debasing slavery, a warning

to all men sent out on the mission of life; and how one’s emotions changed their

notes in the successive scenes that came before us! Of the records as

imperishable as the life of the figures on Keats’s Greek urn. In talking of

painters like Romney, Constable, Turner, and Leslie, who had found friends and

patrons in Lord de Tabley and Lord Egremont, full recognition was made of the

services of those lovers of painting in opening a way for British art outside of

portraiture, to which at first it seemed confined. "Do not, however," said

Wilkie Collins, "think that these noblemen were any but signal exceptions in

their attitude towards art. Of the English aristocracy the majority have no care

for their country’s art. The works of the old masters, done for the satisfaction

of the Church centuries ago, which some of them collected, might all have been

bought for English collections without advancing British art one whit. The men

who really opened the way for you painters were the manufacturers when finding

themselves rich enough to indulge in the refinements of life. ‘We want works

that will be within our own intelligence and that are akin to our own

interests,’ they said. ‘Jupiter, Venus, and Minerva, and such gentlemen and

ladies may be proper to high society, and the pictures of the Virgin and Child,

as also subjects of apocryphal tradition, are strictly in the vogue, but we want

beautiful works for our own living rooms, and we prefer those which treat of

matters within our own comprehension, which we can only get from men of our own

time and our own national sentiments.’ Those were the appreciators who founded

English art, and they showed their good British common-sense. You artists and

the whole country owe them a debt of gratitude for having done it. Beforehand.

English painters rarely found employment except in doctoring old masters

suffering from decay." Wilkie Collins had knowledge of the interests of art for

more than one past generation; thus he spoke with authority on the matter.[I

310-311]

[WILKIE COLLINS ADVISES ON SELLING PAINTING]

VOL II CHAPTER VII 1858-59, 1860

…The position of ourselves in relation to Dickens was a delicate

one. His attack in Household Words upon Millais’ picture of 1851 had

revealed the strongest animus against our purpose, and thus our partiality for

him was exercised only by the reading of his works; but he was a great friend of

Wilkie Collins and of his family, their good-souled mother, in the years of my

absence, had arranged a meeting of Millais and the great author at dinner, it

resulted in removing all estrangement, and in making Dickens understand and

express his sense of the power of Millais’ genius and character.

Millais always spoke of the meeting with satisfaction, but a letter written by Dickens a few days after the dinner needlessly and ungraciously endorsed the sentiments of the original violent article, and so again alienated the confidence of our circle from him.

Wilkie Collins began his reputation by writing the life of his father, and by the novel entitled Antonina. He had made previous essays in painting; one example by him was exhibited in 1849.

The biography and his classical romance were the trial pacings of his Pegasus, and he was now exercising his powers in serial Christmas numbers and the like. At the time that he was writing Mr. Ray’s Cash-box [sic], Millais painted the admirable little portrait of the young author now in the National Portrait Gallery, which remained to the end of his days the. best likeness of him. It will be seen he had a prominent forehead, and in full face the portrait would have revealed that the right side of his cranium outbalanced in prominence that of the left. Dickens contracted the closest friendship with Wilkie, and they were collaborators together in Christmas numbers—in this kind of work the younger writer became a favourite of the first order. Personally Wilkie was entirely without ambition to take a place in the competition of society, and avoided plans of life which necessitated the making up of his mind enough to forecast the future. In this respect he left all to circumstance; but although a generous spender at all times, he was prudent with money affairs. No one could be more jolly than he as the lord of the feast in his own house, where the dinner was prepared by a chef, the wines plentiful, and the cigars of choicest brand. The talk became rollicking and the most sedate joined in the hilarity; laughter long and loud crossed from opposite ends of the room and all went home brimful of good stories. When you made a chance call in the day, he would look at you through his spectacles, getting up from his chair to greet you with warm welcome. He would sit down again, his two hands stretched forward inside the front of his knees; rocking himself backwards and forwards, asking with deep concern where you came from last. If he saw your eyes wandering, he would burst out: "Ah! you might well admire that masterpiece; it was done by that great painter Wilkie Collins, and it put him so completely at the head of landscape painters that he determined to retire from the profession in compassion for the rest. The Royal Academy were so affected by its supreme excellence and its capacity to teach, that they carefully avoided putting it where taller people in front might obscure the view, but instead placed it high up, that all the world could without difficulty survey it. Admire, I beg you, sir, the way in which those colours stand; no cracking in that chef-d’oeuvre, and no tones ever fail. Admire the brilliancy of that lake reflecting the azure sky; well, sir, the painter of that picture has no petty jealousies, that unrivalled tone was compounded simply with Prussian blue and flake white, it was put on you say by a master hand, yes but it will show what simple materials in such a hand will achieve. I wish all masterpieces had defied time so triumphantly."

There was a portrait of his mother by Mrs. Carpenter, her sister, which represented her in youth and girl-like beauty, and it reminded me how she had said that when young, at an evening party Samuel Taylor Coleridge had singled her out and had talked with her for twenty minutes in the highest strains of poetical philosophy, of which she understood not a word, nothing but that it flowed out of the mouth of a man with two large brilliant blue eyes. She wondered why he should have chosen to talk to her. The unpretending portrait explained the riddle.

Wilkie’s room was hung with studies by his father, and beautiful coast scenes of the neighbourhood of the Bay of Naples.

"But tell me, Holman," he said once, "what are you going to do with this wonderfully elaborate work of yours begun in Jerusalem? You must take care and get a thundering big price for it or you will be left a beggar" I replied, "The truth is, my dear Wilkie, I am rather getting reconciled to the prospect looming before me that I shall not sell it at all, for no price such as those which picture buyers are accustomed to give, £1000 or £1500 at the most, would put me into a position to recommence on another Eastern design, and I have no inclination to work to enrich picture dealers and publishers alone. I have many reasons to think that the public will be really interested in it, although the canvas is not a large one; I wish it were three times as big, it would have cost me less labour; I am told it will make an attractive and remunerative exhibition, and this will persuade some publisher to buy the copyright. I have no doubt that it will help my position as an artist, and bring purchasers for my other works. I shall soon pay outstanding. claims, and have this picture to the good, yet I don’t want to waste my time on business, and I should be very glad to find some dealer to take it off my hands."

"Now," he demanded, "what would really pay you fairly, as a professional man?"

"Nothing. less, I assure you, than 5500 guineas—a price that has never been given in England for a modern picture," I said.

"Well, you ought to be able to get that; have you any nibbles?"

"Yes, nibbles of small fry but no bites; private people have asked me to let them have the first refusal of it. They certainly expect that I shall ask a handsome price; I shall not tell them till it is practically finished, and then I know they will be scared off and give it up, and only one will remain—Gambart, the dealer, who is prepared to go farther than the others, but ruled by the usual standard he will shy at my figures."

"I will tell you what you should do," he suggested, "Dickens is not only a man of genius, he is a good business man; you go to him and ask him to tell you whether you could not make the terms so that, keeping to your price, you will still get what you want from the dealer. Gambart is a sharp man, but being sharp, he knows better than to lose your picture, but you must give him the offer in a practicable way, and Dickens will tell you how to do this."

"But, my dear Wilkie, although Mrs. Dickens was kind enough to ask me to her house to see your, ‘Frozen Deep’ acted, and though when I have met Dickens he has been civil and pleasant, I have no reason to think that he has any kind of sympathy for my art, and accordingly I could not expect him to like being appealed to in this matter."

"Don’t you have any such thought. I will speak to Dickens, and you will see he will be very glad to help you," rejoined my eager friend. Shortly afterwards Dickens asked me to come and see him in Tavistock Square. [II 185-189]

[WILKIE COLLINS ON HEARING OF THE DEATH OF AUGUSTUS EGG]

VOL II CHAPTER IX 1862-1864

...Augustus Egg had become so far affected in health that he now wintered

abroad; this year he went to Algiers, and we were all hoping that he would

return, when we heard of his death.

When I took the news to Wilkie Collins he was quite broken down, and rocked himself to and fro, saying, "And so I shall never any more shake that dear hand and look into that beloved face! And, Holman," he added, "all we can resolve is to be closer together as more precious [one to the other] in having had his affection." [II p237, extra words added in 1913 edition]

[WIT OF HARRIET COLLINS]

VOL II CHAPTER VI 1856 – 57 – 58

…Mr. and Mrs. Combe now agreed that I had been right in my

judgment of the course that I should take towards the Academy, and they then

told me what had induced them the more to wish me to court the protection of the

powerful Institution. Mrs. Combe in the previous year had been in London on the

artists’ show day, and Mrs. Collins, the widow of the Academician, undertook to

take her to the leading studios: as they entered the room of one of the

favourite members, crowded with amateurs and picture buyers, the artist received

the lady he knew with, " Ah, Mrs. Collins; now you are the very person to tell

us whether it is true that Holman Hunt has found some fool to give him 400

guineas for that absurd picture which he calls ‘The Light of the World’?"

"It is quite true," was the reply of the lady, who had a spirit of humour now not unmixed with asperity. "And you will perhaps permit me to introduce you to the wife of ‘the fool,’ who will confirm the statement." [II pp146-147]

[CHARLES COLLINS ANECDOTE]

VOL I CHAPTER VIII 1849-1850

.Late in the evening the van arrived, and my kindly landlord

and his wife asked leave to look on while I was putting the final touches of

loving anxiety. At this juncture Millais came, bringing as a new visitor Charles

Collins. I had no time but for my picture. While I confided it to the men,

taking care that the covering did not touch wet paint, I could hear the most

amusing cross assumptions going on between the old couple and Collins, whom I

had known before only at the Academy schools.

"It is an unspeakable gratification to me, believe me, to have the privilege of seeing such a noble picture as this by my old fellow-student. You must, I am sure, understand what reason you have for pride in it, and you must really permit me to congratulate both of you, as well as himself, upon its production," said Collins.

"Indeed we are, sir," replied the old gentleman, "thoroughly proud. I shall be so, sir, to the day of my death at the remembrance of its development under my own roof. The artist is young, sir, young, but he is most industrious, morning, noon, and night; I assure you it is all the same to him."

"You have been so wise in encouraging him," said Collins, "and now there can be no doubt you will be rewarded."

"Well, sir, it’s very little that we could do. I am sure had we been called upon to do more we should have been only too glad; we are indeed more than recompensed."

"Just stop Collins," I said, in passing, to Millais; "he thinks the good old couple are my father and mother!" What a relief it is to send off a picture at which one has been working for months! It seems like cutting a cord binding one to a mill-stone. When we sat down we each compared our feelings, which in my case were complicated by the fact that I had not once seen Millais’ picture, and that now it was out of sight for a month. Collins had sent in his year’s labour in a picture of "Berengaria seeing the Girdle of Richard offered for Sale in Rome." Under the influence of Millais he had in this work discarded his early manner, and striven to carry out our principles. [I 200-210]

[CHARLES COLLINS WITH THE COMBES AND BENNETT]

VOL I CHAPTER IX 1850-51

…Indulgent Fate, however, had in store for me a means of relief

from further buffetings that season. Millais and Charles Collins had been

painting together at Abingdon. Mr. and Mrs. Combe of the University Press heard

of them from Dr. Martin, who, to satisfy their curiosity, introduced Millais;

the Oxford couple shortly after drove over to visit the artists at their work.

The young painters had jocularly recounted the hard fare to which they were

reduced by the uninviting cuisine of their landlady. In a few days Mr. and Mrs.

Combe reappeared, their servant being armed with a tempting pie. The visitors

both delighted in the perfection of the partially finished pictures, and enjoyed

the buoyant. spirit of the young painters. Finding the landscape was nearly

completed, they invited the youths to come and continue their work in Oxford,

where there were good opportunities for painting further accessories in their

pictures.

At the Clarendon Press they became acquainted with Mrs. Combe’s uncle, Mr. Bennett. He was a gentleman of very mature years, rich and not inconsequently inclined to indulge the caprices of old age. Mr. Combe was churchwarden of the parish, and many of the visitors at meals were clergymen. It was but occasionally that any of these stayed at table after the host, who, having no disposition to sit over his wine, habitually went away with the ladies, leaving Mr. Bennett to look after the guests. The old gentleman, as I have heard, was at times disposed to resent his host’s independent and over temperate course, but he became very confidential with his convives, and more than once began his colloquy by looking around to see that there were no black frocked gentlemen still in the room, and, beckoning to the remaining guests, addressed them thus: "Look ye, I don’t like your priests after the order of Melchisedek, they don’t suit me, and if this fashion of leaving guests alone after dinner didn’t take away the priests too, I should the more dislike it. My niece’s husband ought to stay to hand round the wine, but, by Jove, it is good of him to go, if otherwise the High Priests and the Levites would have to stay with him." With a deaf talker’s "Eh! eh!" he went on, "Wine does a man good; it never did me any harm, you see, and I’m getting on in years. Ah, I’ve known lots of friends disappear because they did not put good port wine under their Waistcoats. Take my advice, follow the right sort, be good fellows. Take a glass with me now. I drink to ye, gentlemen." After such avowals once he went on: "Now I tell you what, I will trust you. I want a little advice about a very delicate business. Well, ye know, I’ve been here several weeks, and Pat’s (Mrs. Combe’s pet name) husband has been very kind, although he leaves me a good deal alone. Well, well, he’s a busy man. Now I have given them a deal of trouble, and I want to make them a handsome present. Now what d’ye think they’d like? That’s the question. Eh?"

"Why, my dear Mr. Bennett," said Millais, "I will tell you the very thing of all others. It’s Hunt’s picture in the Academy. You’ve heard them talking about it, for they saw it at the Exhibition, and they admired it, and they’ve said often in your hearing they wanted to see it again. Is it not the very thing, Charley? " and Collins endorsed the opinion warmly in judicious tone. "Why," continued the first, "Hunt only wants t6o guineas, and in a few years I will undertake to say it will be worth ten or twenty times the sum."

"Do you really think so? Eh? eh?" said the old gentleman.

"I am sure of it," said Millais.

"But now the Exhibition is over, our friends can’t see it again. What can we do? Eh? eh?"

"Why," returned Millais, "I will write to Hunt, and he’ll send the picture here, and you shall see it yourself." Capital," nodded the old gentleman, "but don’t let them know yet; keep it a secret till the painting comes." After this momentous conference the next post conveyed a letter from my friend with the urgent request that the picture should be dispatched immediately, and accordingly I had it packed and forwarded. On its arrival in Oxford all was determined so speedily, that in a day or two I received a letter containing a cheque for 160 guineas signed by Mr. Combe.

It seemed from the name of the drawer of the draft that after all the purchaser was not Mr. Bennett, but I know the business began as above described. What an act of practical generosity it was that my brotherly rival thus performed! I was at the time helpless and without the prospect of carrying on the emulative competition we had entered into. How few would have had faith to recognise the chance which Mr. Bennett’s passing whim afforded to benefit a friend, but he, regarding my welfare as dear to him as his own, again secured to me the opportunity of carrying on the contest with him, which, it will be seen, he continued to do until I had found my fair chance of making my effort by his side. Perhaps a clue to the non-appearance of the name of the old gentleman in the cheque may be found in the fact that once he in a testy humour told Mr. Combe that he was not considered as much as he should be, on which the latter said all his house were glad to have him as guest while he was happy there, but that if he failed to find himself so, it would be much better that he left. This outspokenness the old gentleman declared would prove to be costly, and it was afterwards said to be the reason that Mrs. Combe—who was his favourite niece—was left with no advantage over the others.

My receipt of the 160 guineas brought to a conclusion for the time a period of sore trouble, and I revelled in the peace obtained for further work. [I 232-236]

[CHARLES COLLINS REJECTED AS PRB]

VOL I CHAPTER X 1851

…On another occasion Millais referred to our rejection of

Charles Collins, when proposed for election as a P.R.B., adding that it had cut

Collins to the quick. I argued,

"You can understand that the question of his rejection was affected by the present condition of the nominal Body. We two were the practical members at the beginning, and we are the only ones still, in the eyes of the general public, seeing that Rossetti has never exhibited at the Royal Academy at all."

Millais replied: "What Rossetti does at the present time I know very little about but from your report; even when I see him in town he seems little desirous to court intimacy, but I can quite believe that, as you say, the designs he does are full of excellence; his drawings were always remarkably interesting, but I want to see in them a freshness, the sign of enjoyment of Nature direct, instead of quaintness derived from the works of past men. I hoped Pre-Raphaelitism would give him this, but I don’t see much sign of it." [I p266]

[CHARLES COLLINS'S DEVELOPMENT]

VOL I CHAPTER X 1851

…After the completion of the lady’s portrait by Millais, Charles

Collins joined our party. He was the son of William Collins, R.A., the younger

of two brothers, the elder being Wilkie, who became the novelist. Charles had,

while still a child, shown a talent which had induced Sir David Wilkie, a great

friend of his parents, to declare that he must be a painter. I had known him at

the British Museum. He was then a remarkable looking boy with statuesquely

formed features, of aquiline type, and strong blue eyes. The characteristic that

marked him out to casual observers was his brilliant bushy red hair, which was

not of golden splendour, but yet had an attractive beauty in it. He had also a

comely figure. While still a youth he imparted to me his discomfort at the

striking character of his locks, and was anxious to find out any means of

lessening their vividness. As he was one of the successful students in his

application for probationership at the Royal Academy when I failed, our boyhood

intimacy ceased. In succeeding years he obtained places for two pictures, one of

"Eve," after the manner of Frost, and another of "Ophelia " reaching up to pluck

the spray of willow. Later he came under the influence of Edward Ward with a

picture of "Charles II." when in exile unable to pay his reckoning at an inn. He

then suddenly revolted to Pre-Raphaelitism with his picture of "Berengaria."

Changes in his views of life and art were part of a nature which yielded itself

to the sway of the current, and he only ultimately found out how this had led

him into unanticipated perplexities. He was now bent on painting the background

of a Nativity with chestnut foliage and arboreal richness; to paint this he

joined Millais and me. [I 271-272]

[WEDDING OF CHARLES COLLINS]

VOL II CHAPTER VIII 1860-1861, 1862

…It was a pleasure to all his friends to hear that Charles

Collins was engaged to Miss Kate Dickens. I was invited to the wedding at Gad’s

Hill, where many good friends were present. When at school I used to hear the

name of "Boz" in connection with the Pickwick Papers, and the two words

met my eyes as inseparable on all the advertising boards of the circulating

libraries until the name of Nicholas Nickleby superseded the earlier

announcement. What an unrealisable dream it would have seemed to me then, had it

been forecast, that I should be a guest at this magical writer’s table on one of

the most personal and sacred events of his life. He was not yet advanced in

years, but rich in laurels and still multiplying them, with a name honoured

around the world, and a distinction coveted without envy. Yet he revealed a

certain sadness during the feast, and this it was that induced him, when Forster

rose up to make a speech, to command him not to proceed.

It was a lovely day, and when the ladies left the room and we stood up, no more graceful leader of a wedding band could have been seen than the new bride. ...

After the wedding breakfast it was my fortune to drive out about Rochester with dear old Mrs. Collins and John Forster. [II pp216-217]

|

|

|

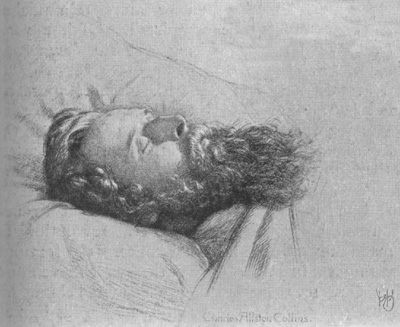

[DEATH OF CHARLES COLLINS] VOL II CHAPTER XII 1873-1887 …I stayed a time in London to paint a few family portraits, and while preparing for the exhibition of my picture I frequently saw my friend Charles Collins. He was much debilitated in health, sad, but always philosophical, yet as perplexed as ever to make up his mind as to which of any two courses he should adopt. One morning he, in the company of Millais, came over to me while I was at work; he was more feeble in his gait than had become habitual with him. I went out with him and Millais to the landing, and stood watching them as they descended It was the last time I was ever to see him alive, for in a few days I was standing by his bedside drawing his portrait as he lay dead. This I gave to his brother Wilkie, who in the end left it to me. On his bed lay, the canvas, taken off the strainer, with the admirably executed background painted at Worcester Park Farm. For the last few years he had not touched a brush, being entirely disenchanted with the pursuit of painting; yet his delicacy of handling and his rendering of tone and tint had been exquisite. Certain errors of proportion marred his picture "Convent Thoughts," or it would have been a typical work of unforgettable account despite its puerile leading idea. At the time of the vacancy in our Brotherhood occasioned by the retirement of Collinson, I judged him to be the strongest candidate as to workmanship, and certainly he could well have held the field for us had he done himself justice in design and possessed courage to keep to his purpose. In his last artistic struggle Collins continually lost heart when any painting had progressed half-way towards completion, abandoning it for a new subject, and this vacillation he indulged until he had a dozen or more relinquished canvases on hand never to be completed. Of late years he had taken to writing, writing a New Sentimental Journey and A Cruise upon Wheels. [II pp312-314] |

From Pre-Raphaelitism and the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood by W. Holman Hunt, 2 vols, Macmillan & Co., London 1905