1928

Shapes that Pass

|

|

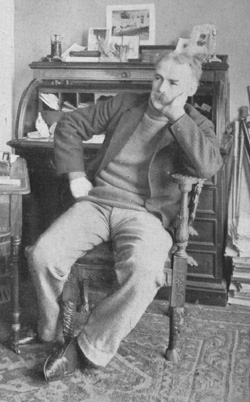

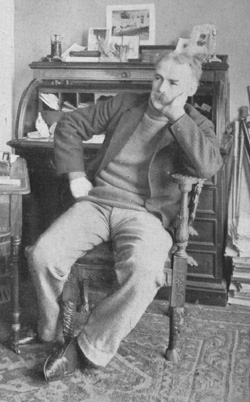

| Julian Hawthorne (1846-1934) was a novelist and the son of

the more eminent writer Nathaniel Hawthorne. He had strong views on his

fellow writers. Here we get him on Wilkie, apparently in 1870 when Collins

was aged 44. This eye-witness account of a visit contains an anecdote about

Wilkie's absent-mindedness. Wilkie had no correspondence with either

Hawthorne though he did send a copy of Nathaniel's Twice Told Tales

to his mother when she wanted books to read during her final illness (To

Harriet Collins 16 September 1867 Public Face II 85). Hawthorne is

seen here aged 52. |

Francillon was a novelist and journalist, steady, standardised,

meritorious, uninspired. …He did, however, break loose once a year to write a

Christmas story, romantic, extravagant, miraculous ; and in the title of each

of them he would include the magic word "Golden." He enjoyed doing these

things, and I think them the best things he did. But his Huguenot conscience

forbade him to make a real, three-volume, Mudie novel on such lines. Wilkie

Collins might have served him better as a model than Trollope: Wilkie was no

Huguenot.

…

Dickens had died in 1870: I had met him when he visited New York on his last

lecturing tour in 1868, but was too late to overtake him in London two years

later. But Wilkie Collins still lived, and, not without misgivings, I improved

an opportunity to visit him. It is seldom that a hero measures up to his best

work; but I would risk it.

I found him sitting in his plethoric, disorderly writing-room : there are two

kinds of bachelors, the raspingly tidy sort, and the hopelessly ramshackle;

Wilkie was of the latter. Though the England of his prime had been a cricketing,

athletic, outdoor England, Wilkie had ever slumped at his desk and breathed only

indoor air. He was soft, plump, and pale, suffered from various ailments, his

liver was wrong, his heart weak, his lungs faint, his stomach incompetent, he

ate too much and the wrong things. He had a big head, a dingy complexion, was

somewhat bald, and his full beard was of a light brown colour. His air was of

mild discomfort and fractiousness; he had a queer way of holding his hand, which

was small, plump, and unclean, hanging up by the wrist, like a rabbit on its

hind legs. He had strong opinions and prejudices, but his nature was obviously

kind and lovable, and a humorous vein would occasionally be manifest. One felt

that he was unfortunate and needed succour. To his visitor he was very gracious,

in a distressful way.

"‘The Scarlet Letter’ is one of the great novels. Even the second volume,

where most novelists weaken, is fine; and the third fulfils the splendid promise

of the first."

A noble tribute! "But three volumes? It is all in one."

"Pardon me! Three volumes, and long ones!" And to prove it he toddled to a

bookshelf and reached it down. He was much perplexed.

"You are right: one volume, not over 70,000 words in all! It is

incomprehensible! Such a powerful impression in so small a space!"

"When I read ‘The Moonstone,’ I wished it were longer," was all I could say.

But he would not be comforted. [pp168-170]

...

Wilkie Collins, as I have said, still lingered, not superfluous, but not

indispensable; like an historic edifice, respected, but unoccupied. Like many

other fiction-mongers before and since, he had come to regard himself as a

reformer, seer, and prophet; and if the people didn’t give ear, as formerly,

they and not the book were to blame. George Eliot had better grounds for such a

persuasion; but no story-teller can regard himself as a teacher with impunity.

[p227]

From Shapes that Pass - Memories of Old Days by Julian Hawthorne,

London 1928

go back to biographies list

go back to Wilkie Collins front page

visit the Paul Lewis front page

All material on these pages is © Paul Lewis 1997-2006