1934

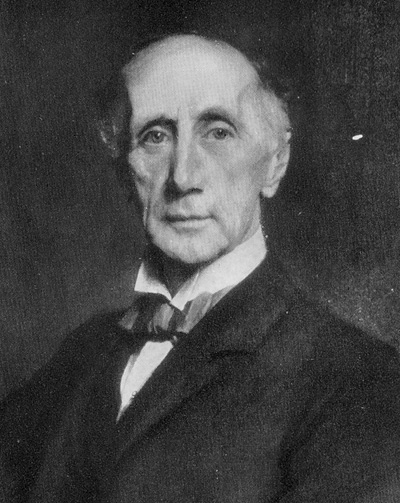

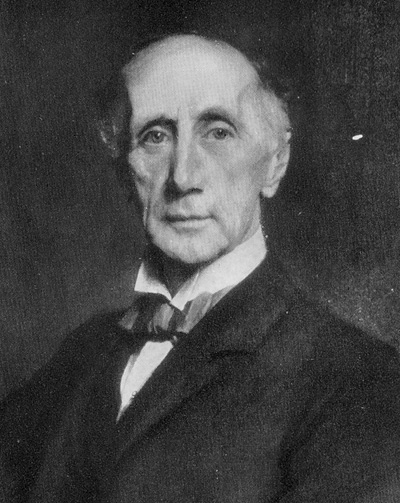

The Recollections of Sir Henry Dickens, K.C.

Henry (1849-1933) was Charles Dickens's eighth child. A defence barrister and King's Counsel he wrote these Recollections in his eighties but died in a traffic accident between finishing them and seeing the book in print. His account of the spiritualist meeting, Dickens's view of The Woman in White, and the tricks at Gad's Hill are found nowhere else. So although his memories of Wilkie are few and disjointed they are valuable nonetheless. He does not say a word about the infamous burning of Dickens's letters on 3 September 1860 at which his sister Katie says he was present. Perhaps this omission is evidence he was was not. His recollections of Charles Collins are even fewer and the two tales here are more about other characters in them than poor Charley.

The portrait above forms the frontispiece to his book. It is is by Luke Fildes and dated 1900

|

Very clearly, also, I do recall the play of “Fortunio” in the following year. Its full title was “Fortunio and his Seven Gifted Servants,” one of Planché’s delightful fairy extravaganzas…Wilkie Collins, who appeared on the bills as Wilki Collini, played the part of the gifted servant with the large appetite, who gulped down a quantity of enormous loaves in papier maché, which he brought in on a large barrow—a most fitting part for him to play because he had the reputation of being a bit of a gourmand. Of course, in the theatricals for the “grown-ups” we children took no active part. “The Lighthouse” and “The Frozen Deep,” written by Wilkie, were serious plays and put upon the stage with all the completeness of a public theatre. I did take a minor share in the production of “The Frozen Deep,” I remember, which was to cut up paper for the snow. (pp5-6) Of the Villa Moulineaux at Boulogne I have a very slight recollection. I have a general remembrance of a lovely garden straggling up the hillside with a blaze of bright colours, and a picturesque kind of chalet called “Tom Pouce,” which was reserved for Wilkie Collins when he was there; (p.8-9) …there were four of us boys who were somewhat bored with life and wanted occupation of some kind or another. In a flash one day a bright idea occurred to one of us, “Let us dig a well.” This we proceeded to do with not altogether unsatisfactory results, for whenever visitors came on the scene to see how we progressed we took care to chalk his or her boots, which necessitated a tip to “pay for the reckoning,” Wilkie Collins being a very constant and not unwilling victim of this levy. (p21) Wilkie Collins was at Gad’s Hill at the time and the hat which he wore was a very large wide-awake. [Hans Christian] Andersen one day, quite unknown to Wilkie, surreptitiously crowned this hat with a large garland of daisies, a fact of which full advantage was taken by the mischievous boys of the family. With apparent innocence, they suggested to Wilkie a walk through the village. To this Wilkie, quite unconscious of his garland, willingly assented; but he must have been somewhat surprised, I think, at the amount of merriment which his presence seemed to arouse in the minds of the villager who passed us on our way. (p35) I remember that on one occasion my father, when talking about literature generally, told us there were two scenes in literature which he regarded as being the most dramatic descriptions which he could recall. One was in fiction, the other in history. The first was the description of the Woman in White’s appearance on the Hampstead Road after her escape from the asylum in Wilkie Collins’s famous book The Woman in White. The other was the stirring account of the march of the women to Versailles in Carlyle’s French Revolution. (p54) The first Lord Lytton was a profound believer in occultism, as his book, A Strange Story, would go to show. In order to open his eyes a little, my father arranged a séance with the popular medium of the day, without disclosing the names of any of the persons who were to attend. He took with him besides Lord Lytton, Wilkie and Charles Collins and the famous conjuror Houdin. This meeting, so far as the medium was concerned, was disastrous. Everything the medium did was promptly “outdone” by Houdin, who really outspirited the spiritualist in all that gentleman’s tricks. But, curiously enough, this did not cure Lord Lytton of his belief and I do not think his faith was ever shaken. (pp63-64) He [Charles Dickens] said on one occasion to Charles Collins: “If you want your public to believe in what you are writing, you must believe in it yourself. I can as distinctly see with my own eyes any scene which I am describing as I see you now.” (p40) On one summer’s day I remember, Millais, Charlie Collins and I went to Maidenhead for a day on the river and we lunched at Skindles, after a loverly morning in a punt. We were smoking on the lawn after lunch when my pipe got stopped up, and none of our efforts were availing to put it right. But Millais was quite up to the occasion. A group of ladies were emerging at the time from one of the luncheon rooms, and Millais, removing his hat in his most graceful manner, asked them if they could oblige him with a hairpin. Luckily, at this time, hairpins were in common use, but I doubt whether in these days of shingling the ladies would have had a single hairpin among them; but at all events on this occasion one of the ladies, taking a hairpin from her hair, presented it to Millais, and all was well. (pp326-327) |

|

|

From The Recollections of Sir Henry Dickens, K.C., London, 1934