1871

Dickens's theatricals

|

|

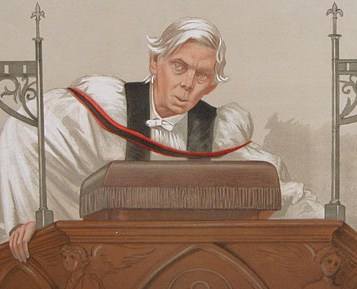

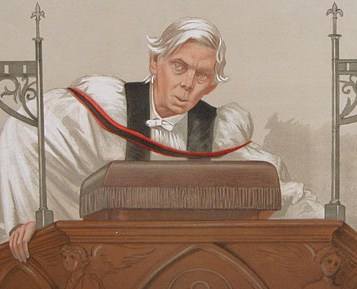

| Alfred Ainger (1837-1904) went to school with Dickens’s sons

and as a teenager took part in the amateur dramatics that Dickens put on in

his house. Dickens thought he had real acting talent. Inevitably this

reminiscence, written just after Dickens’s death, is more hagiography than

history and the few mentions of Wilkie have to be mined from a lot of spoil.

But Ainger does give accounts of Wilkie’s two plays The Lighthouse

and The Frozen Deep so it is not without interest. It was published

in January 1871 by which time Ainger was a Church of England vicar, as he is

shown in this caricature by E M Ward. |

MR. DICKENS’S AMATEUR THEATRICALS. A REMINISCENCE.

IT is now some eighteen years since the present

writer—then in his schooldays—took part in the earliest of those winter-evening

festivities at the house of the late Charles Dickens which continued annually

for several years, terminating with the performance of Mr. Wilkie Collins’s

drama of "The Frozen Deep." And when he remembers the number of notable men who

either shared in or assisted (in the French sense) at those dramatic revels, who

have passed away in the interval, he is filled with a desire to preserve some

recollections of evenings so memorable. Private theatricals in one sense they

were; but the size and the character of the audiences which they brought

together placed them in a different category from the entertainments which

commonly bear that name; and to preserve one’s recollections of those days is

scarcely to intrude upon the domain of private life. The greatest of that band

has lately passed away, and before him many others of ‘° these, our actors; "

and though some remain to this day, the events of those years have, even to

those who shared in them, passed into the region of history.

…

The production next year, on the same stage, of the drama of "The

Light-house," marked a great step in the rank of our performances. The play was

a touching and tragic story, founded (if we are not mistaken) upon a tale by the

same author, Mr. Wilkie Collins, which appeared in an early number of his

friends weekly journal, Household Words. The principal characters were

sustained by Mr. Dickens, Mr. Mark Lemon, Mr. Wilkie Collins: and the ladies of

Mr. Dickens’s family, The scenery was painted by Clarkson Stanfield, and

comprised a drop-scene representing the exterior of Eddystone Light-house, and a

room in the interior in which the whole action of the drama was carried on. The

prologue was written (we believe; by Mr. Dickens, and we can recall as if it

were yesterday the impressive elocution of Mr. John Forster, as he spoke behind

the scenes the lines which follow:

"A story of those rocks where doomed ships come

To cast their wrecks upon the steps of home;

Where solitary men, the long year through,

The wind their music, and the brine their view,

Teach mariners to shun the fatal light,

A story of those rocks is here to-night

Eddystone Light-house—"

(Here the green curtain rose and discovered Stanfield’s drop-scene, the

Light-house, its lantern illuminated by a transparency)

"—in its ancient form,

Ere he who built it died in the great storm

Which shivered it to nothing—once again

Behold out-gleaming on the angry main.

Within it are three men,—to these repair

In our swift bark of fancy, light as air;

They are but shadows, we shall have you back

Too soon to the old dusty, beaten track."

We quote from memory, and here our memory fails. We are not aware that the

prologue was ever published, or indeed the play for which it was written; though

"The Light-house" was performed two or three years later at the Olympic, with

Mr. Robson in the character originally played by Mr. Dickens. The little drama

was well worthy of publication, though by conception and treatment alike it was

fitted rather for amateurs, and a drawing-room, than for the public stage. The

main incident of the plot—the confession of a murder by the old sailor, Aaron

Gurnock, under pressure of impending death from starvation (no provisions being

able to reach the lighthouse, owing to a continuance of bad weather), and his

subsequent retractation of the confession when supplies unexpectedly

arrive,—afforded Mr. Dickens scope for a piece of acting of great power. To say

that his acting was amateurish is to depreciate it in the view of a professional

actor, but it is not necessarily to disparage it. No one who heard, the public

readings from his own books which Mr. Dickens subsequently gave with so much

success, needs to be told what rare natural qualifications for the task he

possessed.

…

The success of "The Light-house," performed at Tavistock House in the January

of 1856, and subsequently repeated at Campden House, Kensington, for the benefit

of the Consumption Hospital at Bournemouth, induced Mr. Wilkie Collins to try

his dramatic fortune once more, and the result was the drama of "The Frozen

Deep," with an excellent part for Mr. Dickens and opportunity for charming

scenic effects by Mr. Stanfield and Mr. Telbin. The plot was of the slightest. A

young naval officer, Richard Wardour, is in love, and is aware that he has a

rival in the lady’s affections, though he does not know that rival’s name. His

ship is ordered to take part in an expedition to the polar regions, and, as we

remember, the moody and unhappy young officer. while chopping down for firewood

some part of what had composed the sleeping, compartment of a wooden hut,

discovers from a name carved upon the timbers that his hated rival is with him

taking part in the expedition. His resolve to compass the other’s death

gradually gives place to a better spirit, and the drama ends with his saving his

rival from starvation at the cost of his own life, himself living just long

enough to bestow his dying blessing on the lovers; the ladies whose brothers and

lovers were on the expedition having joined them in Newfoundland. The character

of Richard Wardour afforded the actor opportunity for a fine display of mental

struggle and a gradual transition from moodiness to vindictiveness, and finally,

under the pressure of suffering, to penitence and resignation, and was

represented by Mr. Dickens with consummate skill. The charm of the piece as a

whole, however, did not depend so much upon the acting of the principal

character, fine as it was, as on the perfect refinement and natural pathos with

which the family and domestic interest of the story was sustained. The ladies to

whose acting so much of this charm was due are happily still living, and must

not be mentioned by name or made the subjects of criticism in this place; but

the circumstance is worth noticing as suggesting one reason why such a drama,

effective and touching in the drawing-room, would be even unpleasing on the

stage. Such a drama depends for its success on a refinement of mind and feeling

in the performers which in the present state of the theatrical art must of

necessity be rarely possessed, or if possessed must speedily succumb to the

unwholesome influences of that class of dramatic literature which alone, if we

are to credit the managers, is found to please at the present day. The fact

further suggests that if the drama as one of the arts which give high and noble

pleasure is to endure, it must be (for a while, at least) under such

circumstances as the private theatricals which Mr. Dickens’s talent and

enterprise have made famous. While the true drama is under persecution in

public, it must find shelter in the drawing-rooms of private houses and the

willing co-operation of the talent and refinement of private life. No theatrical

performance can satisfy an educated taste in which the characters of ladies and

gentlemen are sustained by representatives who cannot walk, speak, and act as

ladies and gentlemen. Such performances as "The Merry Wives of Windsor," "Not so

Bad as we Seem," and "The Frozen Deep," in which Mr. Dickens with his friends

and literary brethren took part, are worthy of being cherished in memory, as

showing that the drama is not superseded by prose fiction, as some persons

believe, but is still capable of affording high and intense intellectual

pleasure of its own.

The production of "The Frozen Deep" has a literary interest for the reader of

Dickens, as marking the date of a distinct advance in his career as an artist.

It was during the performance of this play with his children and friends, he

tells us in the preface of his 1° Tale of Two Cities," that the plot of that

story took shape in his imagination`. He does not confide to us what was the

precise connection between the two events. But the critical reader will have

noticed that then, and from that time onwards, the novelist discovered a

manifest solicitude and art in the construction of his plots which he had not

evinced up to that time. In his earlier works there is little or no constructive

ability. "Pickwick" was merely a series of scenes from London and, country life

more or less loosely strung together. "Nicholas Nickleby" was in this respect

little different. In "Copperfield" there is more attention to this specially

dramatic faculty, but even in that novel the special skill of the constructor is

exhibited rather in episodes of the story than in the narrative as a whole. But

from and after the "Tale of Two Cities," Mr. Dickens manifests a diligent

pursuit of that art of framing and developing a plot which there can be little

doubt is traceable to the influence of his intimate and valued friend Mr. Wilkie

Collins. In this special art Mr. Collins has long held high rank among living

novelists. He is indeed, we think, open to the charge of sacrificing too much to

the composition of riddles, which, like riddles of another kind, lose much of

their interest when once they have been solved. And it is interesting to note

that while Mr. Dickens was aiming at one special excellence of Mr. Collins, the

latter was assimilating his style, in some other respects, to that of his

brother-novelist. Each, of late years, seemed to be desirous of the special

dramatic faculty which the other possessed. Mr. Dickens’s plots, Mr. Collins’s

characters and dialogues; bore more and more clearly masked the traces of the

model on which they were respectively based. It is, possible, however, that

another consideration was influencing the direction of Mr. Dickens’s genius. He

may have half suspected that the peculiar freshness of his earlier style was no

longer at his command, and he may have been desirous of breaking fresh ground

and cultivating a faculty too long neglected. As we have said, we believe that

his genius was largely-dramatic, and that it was the overpowering fertility of

his humour as a descriptive writer which led him at the outset of his literary

career to prose fiction as the freest outcome of his genius. However that may

be, he loved the drama and things dramatic; and notwithstanding what might be

inferred from the lecture which Nicholas administers to the literary gentleman

in "Nicholas Nickleby," he evidently loved to see his own stories in a dramatic

shape, when the adaptation was made in accordance with the spirit and design of

the originator. Most of his earlier works were dramatized, and enjoyed a success

attributable not less to the admirable acting which they called forth than to

the fame of the characters in their original setting. His Christmas Stories

proved most successful in their dramatic shape, and it is difficult to believe

that he had not in view those admirable comedians, Mr. and Mrs. Keeley, when he

drew the charming characters of Britain and Clemency Newcome. His "Tale of Two

Cities" (which, by the way, Mr. Wilkie Collins has somewhere publicly referred

to as the finest of his friend’s fictions in point of construction) was arranged

under his own supervision for the stage, and he seems to have had a growing

pleasure in seeing his works reproduced in this shape, for "Little Em’ly," the

latest arrangement of "David Copperfield," was produced with at least his

sanction and approval; and at the present date a version of the "Old Curiosity

Shop," under the title of " Nell," is announced for immediate production, as

having been similarly approved by himself shortly before his lamented death. In

the present state of the stage we may well be thankful for pieces so wholesome

in interest, so pure in moral, so abounding in unforced humour, as his best

stories are adapted to provide.

Not, perhaps, till the next great master of humour shall have arisen, and in

his turn fixed the humorous form for the generation or two that succeed him,

will Dickens’s countrymen be able to form a proximate idea of the rank he is

finally to take in the roll of English authors. The shoals of imitators who have

enjoyed a transient popularity, by imitating all that can be imitated of. a

great writer—his most superficial and perishable attractions —will have, been

forgotten, and it must then be seen whether the better portion of Mr. Dickens’s

genius is of that stuff which will stand the test of changing fashion and

habits’ of thought. We have little doubt that, to use the words with which Lord

Macaulay concluded his review of Byron, "after the closest scrutiny, there will

still remain much that can only perish with the English language."

From ‘Mr Dickens’s Amateur Theatricals’ by Alfred Ainger, Macmillan’s

Magazine London, vol.XXIII January 1871 pp72-82.

go back to biographies list

go back to Wilkie Collins front page

visit the Paul Lewis front page

All material on these pages is © Paul Lewis 1997-2006