Wilkie Collins set

the crucial confrontation of his novel No Name (1862)

in Aldeburgh on the coast of Suffolk, using the contemporary spelling of

Aldborough. Local people complained that there were at least six ways of

spelling the name of the town. In the 1860s train timetables and local

newspapers used Aldborough, though at some point since, Aldeburgh has become

standard. Wilkie seems to have visited the town at the end of August 1861.

In July he was in Broadstairs, Kent, recovering from an attack of pain in his right side which he blamed on his liver. Wilkie was collecting scenes and material for his new novel, the first after the extraordinary success of The Woman in White. That had gone through eight editions in three months in 1860 in the expensive three-volume format and was issued early in 1861 in a one-volume edition - 10,000 were printed and they soon sold out. Suddenly Wilkie was famous and now he had the task of living up to his reputation with his next novel. On 11 July he wrote, from Broadstairs, to his mother Harriet,

"I came here, last Friday, and propose staying till next Thursday the 18th - when I must get back to London for a week or so to collect all my literary goods and chattels for the writing of my new book. You will be glad to hear that I tried the outline of this said story upon Dickens, that he was immensely struck by it, and that he gave such an account of it to Wills in my absence, that the said Wills's eyes rolled in his head with astonishment when he and I next met at the Office. If I can only write up to my design, I think I can hold the public fast, with an interest quite as strong as in The Woman In White, and with a totally different story."

At this time Collins worked for Dickens on the staff of his weekly periodical All The Year Round. That was where The Woman in White first appeared and the new novel would appear there first too. William Henry Wills was its sub-editor and Dickens and Collins respected his opinions.

Collins was still not sure where to set his new story and his letter to his mother continues

"Sometimes I think of staying here - sometimes, of going to Scarborough - sometimes of exploring the unknown Suffolk coast, and resting quietly at Lowestoft. When I next write to you, or see you, I suppose I shall have settled something."

After returning to London – where he was delayed and much surprised to be offered £5000 for his next book (it would be Armadale) with a bidding process set up for the one he was now working on – he finally visited Whitby, on the North-east English coast in early August. He stayed three weeks at the Royal Hotel, but by the 26th he wrote to his friend Charles Ward that he was leaving because

"The noises indoors and out, of this otherwise delightful place (comprising children by hundreds under the windows, and a Brass band hired by the proprietors to play regularly for hours a day for the benefit of his visitors) are keeping me back so seriously with my work that I must either leave Whitby or lose time…"

He then traveled to York, staying at the George Hotel for two days and leaving on 28th August. It was probably then that he traveled to Aldeburgh. We know that by 11 September he was back in London.

No documentary evidence of his stay in Aldeburgh has been found, though local folklore says that he arrived ‘in the summer, on the train’. Direct trips from London had been possible since 12 April 1860 when the last section of the branch line from Ipswich, off the main London to Norwich route, which was opened in June 1859, was extended the final 5 miles from Leiston to the coast. At the time in which the book was set, July 1846, the line only ran as far as Ipswich and that line had only been extended from Colchester on 1 June 1846. From Ipswich to Aldeburgh was a 30-mile coach journey, taking several hours - a fact not mentioned in No Name. .

But when Wilkie did the journey, if he did, it was all by rail, starting at Bishopsgate station in east London and taking four hours in total, nearly half of that being the relatively short trip from Ipswich. At Aldeburgh the station was nearly a mile from the town and travelers were met by coaches from the East Suffolk Hotel in the High Street to be conveyed to their lodgings.

| As this 1851 railway map shows, Aldborough is well south of the destination Wilkie mentioned to his mother - Lowestoft. Ten years later, with the railway in place, it was becoming a popular coastal town for visitors from London. A fact predicted by Noel Vanstone's father when he bought the house, Sea-View, there. | |

The grandest and oldest hotel in Aldeburgh was - and is - the White Lion, at the north end of the town overlooking the sea and its broad shingle beaches. It is likely - but not certain - that Wilkie stayed there.

In No Name Captain Wragge establishes a household in a villa called North Shingles. A house just to the north of The White Lion is still called North House. It is pictured below.

Many scenes in Aldeburgh are much as they were. Here is how Wilkie described it in No Name.

"Thrust back year after year by the advancing waves, the inhabitants have receded, in the present century, to the last morsel of land which is firm enough to be built on - a strip of ground hemmed in between a marsh on one side and the sea on the other. Here, trusting for their future security to certain sand-hills which the capricious waves have thrown up to encourage them, the people of Aldborough have boldly established their quaint little watering-place. The first fragment of their earthly possessions is a low natural dyke of shingle, surmounted by a public path which runs

parallel with the sea. Bordering this path, in a broken, uneven line, are the villa residences of modern Aldborough - fanciful little houses, standing mostly in their own gardens, and possessing here and there, as horticultural ornaments, staring figure-heads of ships doing duty for statues among the flowers.

Viewed from the low level on which these villas stand, the sea, in certain conditions of the atmosphere, appears to be higher than the land:

coasting-vessels gliding by assume gigantic proportions, and look alarmingly near the windows. Intermixed with the houses of the better sort are buildings of other forms and periods. In one direction the tiny Gothic town-hall of old Aldborough - once the centre of the vanished port and borough - now stands, fronting the modern villas close on the margin of the sea.

At another point, a wooden tower of observation, crowned by the figure-head of a wrecked Russian vessel, rises high above the neighbouring houses, and discloses through its scuttle-window grave men in dark clothing seated on the topmost story, perpetually on the watch--the pilots of Aldborough looking out from their tower for ships in want of help.

Behind the row of buildings thus curiously intermingled runs the one straggling street of the town, with its sturdy pilots' cottages, its mouldering marine store-houses, and its composite shops. Toward the northern end this street is bounded by the one eminence visible over all the marshy flat - a low wooded hill, on which the church is built. At its opposite extremity the street leads to a deserted martello tower, and to the forlorn outlying suburb of Slaughden, between the river Alde and the sea Such are the main characteristics of this curious little outpost on the shores of England as it appears at the present time."

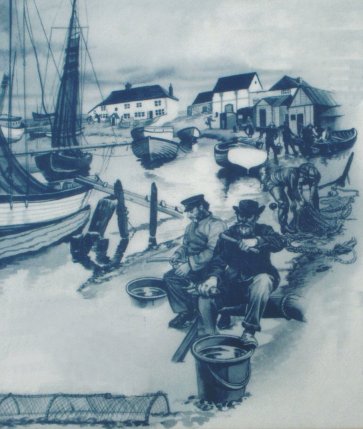

Slaughden has now disappeared into the sea. The impression above shows how it looked in the 19th century.

Joining these places together is the crag path or, as Wilkie called it, The Parade. This path runs along the sea front, on top of the sea defences but looking in most parts just like a path or road. Many meetings and passings-by in No Name happen on The Parade. As Captain Wragge says "There is only one walk in the place...; and on that walk we must all meet every time we go out." Wilkie chose to use its common name. Dame Millicent Fawcett, the campaigner for women's suffrage who was born in Aldeburgh in 1847, says it was not always called that. In her autobiographical What I Remember (London 1924) she wrote

|

|

|

The crag path around 1950 |

"I remember walking along the crag path at Aldeburgh (we always resisted with vehemence any Cockney attempt to call it The Esplanade, The Parade, or any such name."

At the far south end of the crag path, beyond Slaughden, is the Martello tower, started in 1796 and completed only in 1815, which sets the scene for Magdalen Vanstone to set out to Captain Wragge her bold plan to recover her fortune.

.

"Magdalen drew her hand from the captain's arm, and led the way to the mound of the martello tower. "I am weary of walking," she said. "Let us stop and rest here.She seated herself on the slope, and resting on her elbow, mechanically pulled up and scattered from her into the air the tufts of grass growing under her hand."

Then Magdalen goes down to the sea, alone.

|

|

"Another moment, and there came a sound from the invisible shore. Far and faint from the beach below, a long cry moaned through the silence. Then, all was still once more. Alone on a strange shore, she had torn from her the fondest of her virgin memories, the dearest of her virgin hopes. Alone on a strange shore, she had taken the lock of Frank's hair from its treasured place, and had cast it away from her to the sea and the night." |

This picture, signed E. Evans, an untraced artist, shows Magdalen on the shore at Aldeburgh, looking out to sea after throwing the hair of her deserting lover, Frank, into the sea. Behind her a groyne, a wooden breakwater, built into the sea to reduce erosion. They can still be seen. This picture is taken from the 1877 edition published by Smith, Elder.

During her stay at Aldeburgh, and with the assistance of Captain Wragge, she succeeds in defeating the tough and resourceful housekeeper Virginie Lecounte and Magdalen prepares herself to marry the man she does not love, Noel Vanstone. Two days before the wedding, her despair is such that she buys laudanum with the intention of killing herself.

"She removed the cork and lifted the bottle to her mouth. At the first cold touch of glass on her lips, her strong young life leapt up in her leaping blood, and fought with the whole frenzy of its loathing against the close terror of Death."

Finally, sitting at her window in North Shingles Villa she decides to let fate determine if she lives or dies. The choice will be made depending on the number of ships that pass her bedroom window in thirty minutes.

She resolved to end the struggle by setting her life or death on the hazard of a chance.

On what chance?

The picture above is by Wilkie's friend John Everett Millais. His monogram and the date 1863 can be seen at the bottom right of the engraving (for an enlarged version in a separate frame, click on the image). It was done for the first one-volume edition of No Name published in 1864 by Sampson Low, Son, and Marston.

|

|

|

The Parish Church of St. Peter and St. Paul, Aldeburgh around 1950 |

Magdalen lives. And marries Noel Vanstone in Aldeburgh Church. From there the scene leaves Aldeburgh, and the story moves on.

Wilkie was always careful about the detail in his books, checking train times, the law, the effects of poison, and in this case the time it would take a letter to get to Zurich and back in 1846. He even got the moon right. In the novel, just after 10pm on 25 July 1847, Magdalen leaves Sea-View Cottage at the end of her first visit as she tries to charm Noel Vanstone. As they walk home, Collins says "It was a fine moonlight night." And so it was. The moon, just two days from being full, rose over the sea at a quarter to seven and reached its zenith at 11pm.

Aldeburgh vs.1.1 adding pictures and moon details.

26 August 2000