This talk was given 10 May 2012

The text here may not be identical to the spoken text

BUILDING SOCIETIES ASSOCIATION 10 MAY 2012

MANCHESTER CENTRAL

We

have heard about business from John Cridland and about economics from Robert

Parker.

I

am here as a freelance financial journalist who has been writing and

broadcasting about money for 40 years and earning all my living doing that for

more than a quarter of a century. I am not here representing MoneyBox or god

forbid the BBC nor Saga Magazine who I also work for.

In

all that time I have had one clear point of view. The point of view of what we

generally call consumers – but I mean your customers the people who walk into

your branches or log onto your websites – and give you your living.

So

the state of my nation is not the Government’s deficit or its growing debt – now

above £1 trillion again.

Though I will point out that despite all the cuts and the austerity we are not

paying off the nation’s credit card.

Here is the public sector net debt now and a year ago rising in both pounds and

Nor

is my state of the nation the economy in recession.

I

would have a slide here but a bar chart of -0.3% is quite hard to see.

No.

My focus is the state of the people in the nation – consumers, if you like.

Customers if you prefer.

And

they are caught between two things – the economic realities which are bad. And

the political choices which the Coalition government has made to deal with them.

Now

I don’t propose to discuss whether those choices are right or wrong, the best or

the worst, or indeed whether they will work – however that might be measured –

or not. I propose to look at their effects and what that means for your

business.

And

to me pure building society business is simple. You take in money from savers,

pay them for the use of it through an interest rate, and lend it out to

borrowers – principally to buy a home – at a higher cost, with a margin that is

enough to make your living, pay your staff, deal with bad debts and of course

crucially not pay a dividend to shareholders.

Now

you all know that. And you all know, especially the bigger ones, that you stray

from that. But I say them to you because when I was here a few years ago things

were very different. Ten building societies had decided that their future lay

not as a building society but as a bank. And they either converted or sold

themselves to banks – merged with was the phrase used – in the great

demutualisation experiment.

It

failed. Every single one of those societies has lost its identity – either

disappeared into a bank or gone bust or in one case both – and two now owned

largely by the state. Such was the success of the demutualisation programme. I

am proud that, almost alone among financial journalists, I was a demutualisation

sceptic throughout the nineties and the early 2000s before it began to unravel.

Not

because of any pro-mutual principle. But because the arithmetic said that the

conversion from mutual to bank could not work because there was another player

who had to take money out of the business – shareholders leaving less for

everyone else. And all that stuff about PLCs being more efficient and driving

down costs was of course nonsense.

Indeed, what we didn’t know then was that there would be another growing drain

on the resources of banks. Executive pay. The people at the top of the banks now

pay themselves – what? five or ten times the amount that even the best paid

people who run building societies get.

So

with those two big advantages over the banks – no shareholders and executive pay

that is not out of control – you are perfectly placed to challenge them.

So

let me look at the state of the nation in those two areas where you trade –

savings and lending.

Savings

Savings first. Because without that money you’ve nothing to lend it out. In the

pure model. I know you don’t always do that.

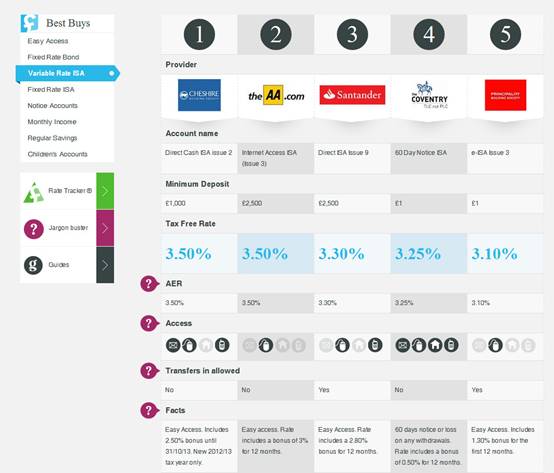

Let

me tell you a story. I decided to open my 2012/13 cash ISA last week. And where

did I go? Cheshire Building Society. Was it because I like building societies?

No. Last year I put my new ISA money with the AA for heaven’s sake. No, it was

because it was the highest rate – 3.5% instant access. No conditions. So

Cheshire has my money. Or some of it.

What about that money I had with the AA? And another ISA with Halifax? That’s

looking for a new home. Because both those deals have collapsed to a low rate.

AA is now 1.7% and Halifax, though it didn’t actually tell me this clearly, is

now a pathetic 0.1%. So is this money with the Cheshire as well? To lend to

footballers in Wilmslow who find it more tax efficient to buy their homes on a

mortgage? No. Cheshire didn’t want it. They only want new money – footballers

again! – old money like mine not interested.

But

hang on a minute, you can transfer another ISA to a Cheshire ISA – its Instant

Access Cash ISA would love to take your money. But it pays a slightly different

rate. Not 3.5% but 0.5%. So on £5000 instead of paying me £175 for the use of my

money it would pay me just £25. For £5000. For a year. Who in their right mind

would accept that? Well lots do.

Leaving the Cheshire cat grinning from ear to ear – like its namesake.

And

what about my 2012/13 money? Will Cheshire want that next year? No. By October

next year my 3.5% return will plummet to just 1% – paying me just fifty quid a

year for the use of my five grand.

So

where is my previous year’s money? From AA and Halifax? Back to

www.savingschampion.co.uk – which let any deals it has with the firms in its

tables affect their position.

The

top paying cash ISA which accepts new money and has no hidden traps is

Santander. So mine is being moved there. Yes. I did choose the second most

complained about bank for banking services, according to FSA complaints data

2011. Largely because I don’t expect to

contact the bank at all during the time it has my money. It will only be there

for a year because, yes, 12 months after I opened it my money will start earning

the rubbish rate of 0.5%.

So

there is a note in my diary in big Santander red type ‘move my cash ISA from

Santander’. And if I do need to take any money out in the meantime I can do that

online without talking to anyone or paying to call Santander’s 0870 customer

profitline.

I

say all this not have a go at Cheshire B Soc or its massive parent Nationwide.

You all do it. And we all know why. If you offered the real rate that you could

afford – 2%, bit more perhaps – then the banks would take all the cash savings.

So you have to do what they do.

But

it is a pretty poor business model isn’t it? You tempt people in with an

unsustainable offer, then you sit back and keep quiet and hope they won’t notice

when you turn a table topping offer into a one below the top hundred.

I

have spent so long on this not to tell you anything you don’t know. But for two

related reasons.

First, to let you know that among all the complaints I get about savings the

relatively poor rates are top of the list. But the fact that you have to work so

hard to find the best deals – not just once but every year or indeed every six

months if you really want to get the best return on your cash.

And

the great unfairness of this is to those who don’t move their money. It’s all

right for me and many listeners and tweeps who know where to go, who know the

traps to look out for, who understand the rules, who have cheap, fast access to

the internet and the confidence to trust their money to it. But every time I

move my money and get 1 or 1.5 percentage points above what you can really

afford to pay, someone else gets 1 or 1.5 percentage points less. So the – what

shall I call them – the astute – profit at the expense of the rest.

So

I probably feel no prouder of doing that with my money than you do with making

these unsustainable offers. We are both trapped by the system.

My

second reason for mentioning it is to ask you if there is a better way? A

building society way?

And

you may have to find one.

Over the last few weeks I have had lunch with executives from a number of banks

and building societies. And every single one of them, when I have raised the

complaints about rates plunging twelve months after an account is opened, every

one has said to me with a note of pride “Oh but we tell customers now when the

interest rate is about to fall.”

And

how crestfallen they have looked when I have reminded them that they do that

because it is the law. The Payment Services Regulations 2009 say they – you –

must. So you do. And don’t think smugly to yourself ‘we did it before that law

came in’. You knew it was on the way.

And

if that law changes behaviour and there are fewer suckers to leave their money

languishing with you at a fiver a year for every five grand you borrow off them

then you will all have to change. And pay people a more affordable rate.

Think on – as they say in this part of the world – think on. And I say that

partly because I was born near here and practising for my twice weekly

appearances on BBC Breakfast live from Salford.

Even with the loss leader rates that savers can get another common complaint is

‘my savings don’t keep up with inflation’.

I

have never understood that complaint.

There are two reasons to save. One is to live off the income. And people who do

that can reasonably complain that they the 3% they struggle to earn – before tax

– is a fraction of what it used to be and of course if they are not active

savers they will be getting 0.1% or 0.5%.

The

other is to save up for something. Now for most consumer goods that is not very

common – people tend to borrow to buy the plasma TV or the new kitchen. And even

if they do save they are not really saving long enough to worry about the

interest earned.

The

most common reason to save is for the deposit on a house. Now house prices are

falling. So as your money grows by 3% a year the property you are chasing is

falling in value – in some parts of the country by 3%. So even a fixed £10,000

in the bank becomes a bigger proportion of the home you want to buy. So it

doesn’t matter what general inflation is. What matters is that you (a) save and

(b) chase the rates.

Mis-selling or Fraud?

Let

me take you to another state of the nation at the moment. Mis-selling.

I

tweet a lot nowadays – @paullewismoney it’s a personal account, not a BBC

account, not ‘complied’ as they call it, so I say what I want within the bounds

of libel and usually commonsense. It has around 31,200 followers – if it was a

magazine with that circulation it would be between

Grand Designs and

Angler’s Mail. I rather like that

thought.

I

can’t offer you a preview of the Carp Show. But I do tweet often about mis-selling.

And I get a surprising number of people who tweet back – from the consumer point

of view – saying ‘what is this mis-selling? Is it just you media protecting the

banks? Surely mis-selling is just a polite word for fraud?’

When I do tweet about mis-selling the spellchecker on the iPad converts it to ‘mis-spelling’.

It may have a point. We should have said the Arch Cru investment was high risk

but we mis-spelled the word ‘high’ L-O-W. And by mistake left out the word

‘extremely’. Proof-reading errors. No more.

But

what about fraud?

Fraud is committed if I lie to you and as a result you give me money.

But

the law goes a bit broader.

First – it is not only lying at the heart of fraud. Anything said which the

person saying it knows to be untrue or misleading which causes the person who

hears it suffer a loss or a risk of loss, is fraud.

Fraud is also committed by failing to disclose information which you have a

legal duty to disclose, and that causes you to profit or the other person to

make a loss.

And

there is also fraud by abuse of position. If you are in a position where you are

expected to safeguard or not to act against the financial interests of another

person and you abuse it by acting or failing to act and you gain or the other

loses.

That was from the Fraud Act 2006 and I recommend sections 2, 3, and 4 to you for

your bedtime reading. It’s one of the shorter simpler Acts of Parliament. And,

as I said earlier, think on.

http://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/2006/35/contents

Mis-selling

is in our minds at the moment. In the last two weeks Barclays, HSBC, Lloyds, and

RBS have set aside an extra £1 billion this quarter to pay compensation for

Payment Protection Insurance mis-selling. That brings the total amount set aside

for the big five banks to more than £7 billion. The final total for all banks,

building societies and smaller lenders could well be more than the £8 billion

predicted a little while ago.

|

PPI PROVISIONS BY BIG FIVE BANKS |

|||

|

2011 |

2012 Q1 |

Total |

|

|

£million |

£million |

£million |

|

|

Lloyds |

£3,200 |

£375 |

£3,575 |

|

RBS |

£1,075 |

£125 |

£1,200 |

|

Barclays |

£1,000 |

£300 |

£1,300 |

|

Santander |

£538 |

£0 |

£538 |

|

HSBC |

£455 |

£290 |

£745 |

|

TOTAL |

£6,268 |

£1,090 |

£7,358 |

Individual amounts are significant – the average is now said by ING to be around

£2600 and it reckons £5.6 billion will be paid out to more than 2 million people

this year. It really is the High Street bank version of quantitative easing.

Pumping new money into the economy.

The

ING research estimates that more than £1bn will be spent on the High Street.

Another £1.9 billion will go into savings accounts. And £2.4 billion will be

used to pay down debt. Which will also release spending power.

Now

I have stood on platforms like this for some years saying that PPI was a waste

of money and was widely mis-sold. And as time has passed the response has

changed from boos to murmurs to silence to the rustling of paper to, now, sage

nods. ‘Oh yes it was widely mis-sold and do you know we are making every effort

to repay it?’ Forgetting to mention that it was only eighteen months ago that

the major banks put all claims on hold pending the court case which they hoped

to win. Only when they lost did they suddenly realise what the law said and what

they had to do.

And

was this systematic mis-selling of unnecessary and unclaimable insurance, in

fact fraud? Giving information known to be untrue or misleading, omitting

information that there is a legal duty to disclose, being in a position where

you should safeguard another’s financial interests and failing to do so – any of

those to make a profit is fraud.

The

more I look into it the more I tend to agree with those tweeps. It goes beyond

mis-selling. There is a respectable legal argument that it was fraud. And on an

industrial scale.

I

put this little interlude in because I will return to mis-selling later.

Lending

But

next – what you do best – lending.

Let

me tell you first what listeners, viewers, and tweeps say to me about the

process now in 2012 of getting a loan to buy a house. A mortgage.

You

need a perfect credit record. If a

customer was on holiday and had a late payment charge on a credit card, or

forgot to pay a mobile phone bill, or argued about a loan repayment and was late

with it, or moved a lot and has not always been on the electoral roll – then

they say they are automatically refused a mortgage. Now I am sure you will say

‘no, no, no. Not true of us’. But I do ask you to be realistic about the real

credit risk of someone who has been late with a couple of payments.

To

get the best deals you need a big

deposit. 10% is good, 15% better 25% pretty perfect. That can cut your rate

by nearly 2 percentage points – cutting monthly payments for the same loan by

£100 or more. So do look at the differential prices between big deposits and

more realistic ones. Building societies are there not to help the rich but to

help the ordinary person or couple buy a home.

And

saving up for that deposit is difficult. Not least because if you are renting

rents are high and of course you get little or no help from the rate of return

on your savings. At least you might hope over the time you are saving the

interest might pay the stamp duty. But that is unlikely now.

Though as I said earlier with falling

house prices your savings are worth a bigger proportion of the price of your

target home.

And

finally house prices themselves. In

many parts of the country buying your first property is impossible on average

pay. Though, it has be said, that in some parts it is possible.

Now

I said earlier I am not an economist. And I’m not. But there is one economic law

that is self-evidently true. Often called the law of supply and demand. If there

is a shortage of a product the price goes up. If there is a surplus the price

goes down. So if the supply does not meet the demand then prices must go up. I

have been known to say that this is the only economic law that always works. It

is an iron law, the e=mc2 of economics.

But

with property we have a strange situation. There is a shortage of property.

Every report into the supply of property from family formation, immigration, and

the choice we want to make of living alone shows us that we need to build

perhaps 250,000 homes a year yet we are building barely 100,000. So there is a

shortage of homes – and that affects the rental market as well as the purchase

market. It should be putting up prices. But if we look at house prices in the UK

as a whole they are pretty flat. In places falling, in others rising. Because it

is not enough just to want a home of your own – you have to have the means to

buy it.

And

let me be clear about home ownership. In the UK as in most of Europe buying a

home is the most sensible option. First, it gives you security in old age. If

you rent then when you retire and your income falls you will have to move to

somewhere you can afford – which you may not want to do.

Second, it gives you a home in a way that rental cannot. At least not in the UK.

Not now. Buy to let created a whole new form of tenancy – assured shorthold.

Where the only thing assured for the tenant was that after six months they could

be asked to move at two months notice. The landlord needs no reason and it has

happened out of the blue for many people living near the Olympics site for

example. In other words shorthold tenancies are fine for young people not

settling down looking for somewhere to camp for a short time. But it is not

suitable for a person who wants to settle down in an area or have a family. But

for fifteen years every new tenancy has automatically been an assured shorthold

tenancy.

No

surprise then that rents rise rapidly to the highest level enough people can

pay. It is a scheme designed for the convenience of landlords – particularly of

course the new market (I say ‘new’ in a historical context) of buy to let.

Lenders will only lend for buy-to-let if the letting is an assured shorthold

tenancy.

There is an alternative – an assured tenancy where you can only be evicted for a

tenancy offence – not paying your rent for example. If you lent on buy to let

for those tenancies as well – or indeed on ethical grounds only on those

tenancies – then life would be a lot better for many tenants.

So

until we have a more balanced rental sector – balancing the rights of tenants

and landlords more evenly – then buying a home is a sensible thing to do. Hence

the desire to do so.

I

explained earlier the barriers that were being put in the way of aspiring home

owners. And it is the balance between these two competing forces that keeps

house prices in a rather unstable stability. In London and the southeast of

England things are a bit different. There estate agents tell me prices are high

and rising because there are many buyers with cash – many from overseas – and

perhaps more now after the French and Greek elections – wealthy people with cash

to buy in a strong, desirable and finite market. So prices rise. In other places

where the economy is declining, work is disappearing, and prices are falling as

demand moves elsewhere. And some of that demand of course comes from buy-to-let

landlords.

Now

in some ways the price of a house doesn’t matter if you already have one. I

don’t care if my house is worth £5, £500,000, or £5 million. It is still worth

one house. And when I want to move I shall sell it for the price of one house

and use that money buy another which will also be worth one house.

That is not how houses have been seen though. In the long period of house price

inflation a house has been seen as an investment, as a piggy bank, as a pension

– sometimes all three. Indeed we even had pension mortgages at one time.

But

for some groups the price of a house does matter. Those who don’t have one are

very affected by the price of entry to the market. Those who have more than one

do get very concerned about what that strictly unnecessary home is worth. And

then there are the four million with interest only mortgages.

I

have often said that endowment mortgages – when interest only was invented – was

mis-selling. All of it. You were selling a certain debt of known amount due to

be repaid at a fixed time and also selling to repay it an investment whose value

would go up and down and was not guaranteed to meet the certain debt at the

fixed time. They were mis-sold because they claimed to offer a certainty that

the endowment policy would provide sufficient to repay the loan and extra to

give you a lump-sum as well.

So

imagine what I think about interest only mortgages with no repayment vehicle in

place.

Of

course they can seem like a good idea. Because there is no capital repayment the

monthly payments are lower. So for a fixed budget you can buy a bigger place.

And at the end of the loan – twenty five years – of course the price of property

will have increased and you can use that profit to buy yourself a smaller home

for your retirement. And if at some point you need to buy somewhere else then

wages keep on going up don’t they – so with capital gain and higher pay you will

be able to replace it.

And

now we see the problem. Interest only loans were predicated on rising house

prices and rising pay. If either or both of them fail to do that then it is a

less sensible option. At the end or in the middle of the loan you could have no

equity in the home – or no more than your deposit – so you will not be able to

buy somewhere else. And of course you will be older and may not have another 25

years to buy somewhere. After 25 years of paying the interest on a loan you may

have no equity, no home, and no means of borrowing more. So rising house prices

are crucial to the interest only borrowers.

The

question is, were these loans mis-sold or mis-bought?

I

don’t know the answer to that question. People with these mortgages have said to

me that they went into it with their eyes open that they were the only way to

achieve what they wanted they were perfectly happy with their home thank you

very much. And what happens at the end? Oh, something will turn up.

Ah,

Wilkins Micawber right on cue.

But

the banks did not think that they were mis-selling PPI. 795 IFAs did not think

they were mis-selling investments in Arch Cru recently – and now have to find

£110 million to compensate them – about a third will go bust as a result. And in

the first mis-selling scandal – for which the word mis-selling was actually

invented along with the modern financial services industry in the early 1990s –

the pensions mis-selling scandal – I doubt if the thousands of commission driven

sales staff who mis-sold £11.5 billion of pensions thought they were doing

anything wrong either.

So

be prepared.

And

let me tell you how to protect yourself against mis-selling in the future. It’s

dead easy.

End

commission. Something else I have been banging on about for years. And like many

other things – PPI, regulating products not sales – I have been proved right and

my views have become mainstream. It is going for investment products from

January. But it will remain for insurance products – which is why many IFAs are

switching to selling those. And the FSA made it clear in December that it would

not be banning commission in the sale of mortgage products.

Commission is the driving force which leads to misrepresentation – which drives

the salesperson to put their own interest ahead of their client’s. And what does

misrepresentation mean – fraud.

My

final message to you is get rid of commission.

Think on.

Thank you.