This talk was given 23 June 2011

The text here may not be identical to the spoken text

WELSH LOCAL GOVERNMENT ASSOCIATION 23 JUNE 2011

I’m

Paul Lewis a freelance financial journalist. Among other things I present Money

Box on Radio 4. But I am here today to talk on my own account and not to

represent any of my clients including the BBC.

My

talk today is called Pensions and deficit (with a bit on inflation). In fact it

is two bits on inflation – one after pensions and one after deficit. but I

mention it separately because I think inflation is the real financial problem

that we face – and the one that no-one is addressing.

Pensions

Let

me start by saying you should not object to local government pensions being

described as ‘gold-plated’. Gold plated means something made of copper and then

covered it with a microscopic layer of gold as little as half a micron (2000 to

the mm) thick to make it look valuable. Golden watch cases and jewellery are

often just gold-plated copper. So if your pensions are called gold plated rather

than solid gold you should be grateful. And you may well say to me that in

future they will only be gold plated.

There are three changes planned for your pension and they are accurately summed

up in the familiar phrase pay more, work longer, get less. So my job today is to

explain what I understand the extent of those changes, consider whether they are

fair, and look at what compromise might be on the table.

Pay

more

You

all know I am sure that the plan is to increase contributions to public sector

pensions by 3.2% - or rather 3.2 percentage points because the plan is to raise

contributions from, say, 6% to 9.2%. Which is a rise in the money you pay out of

your salary of more than 50%.

When the original percentage announced in October of 3% rose to 3.2% my

understanding was that the extra 0.2% came from the promise that the armed

forces would see no rise – indeed make no contribution as they currently pay

nothing and will continue to pay nothing. That promise was made by the Prime

Minister and confirmed by the Chancellor in his Budget speech this year. My

belief was that the 0.2% will meet the cost of not increasing that zero

contribution. But the Treasury tells me that was not the case and the need to

raise the money £2.8bn a year was the reason for the rather odd 3.2% average

increase. I might also point out that the concession for the armed forces

applies not just to the privates and sergeants and captains risking their lives

and limbs in Afghanistan it also applies right up the ranks to the Admirals,

Generals and Chiefs of Staff sitting in Whitehall advising the Government – if

they are in uniform.

Danny Alexander announced on Friday that anyone earning less than £15,000 a year

would also see no rise in their contributions and those earning between £15,000

and £18,000 would face a rise of just 1.5%. Or did he? That is what he said but

in the written material those numbers were expressed as £15,000 (FTE). Now what

that means is that the freeze and 1.5% rise will apply to those in posts whose

full time equivalent salary would be less than £15,000 or less than £18,000. So

a part-timer earning £10,000 a year could easily be earning too much to get

either of these concessions.

I

was told yesterday by the Treasury that this is a proposal and that how this

applies to low paid people is still up for negotiation.

What will happen above those levels we do not know. That is also part of the

negotiations that are going on at the moment – though it might be helpful if the

Government did not keep popping out and saying what they were going to do. But

for the higher paid it could mean contributions rising by five percentage

points. And of course the most important thing is to be clear what the rise will

be for those earning the average – around £26,000 a year.

Whatever the outcome of those negotiations – behind closed doors, in speeches to

the IPPR, or on the streets and picket lines – there seems little doubt you will

have to pay more. The question is – should you?

There are still a lot of final salary pension schemes in the private sector –

though the number is declining and the number open to new members is now very

small. Contributions into those schemes are collected each year by the Office

for National Statistics. And the latest figures from Pension Trends are in this

graph.

Source: Office for National Statistics Pension Trends April 2010 Chapter 8

For

final salary scheme, or salary related schemes in fact, the average total

contribution going in is 21.5% with the employee paying 4.9% and the employer

paying 16.6%.

So

if your contributions are currently 5.5% to 7.5% depending on the scheme, you

are already well above the average.

Source: Office for National Statistics Pension Trends April 2010 Table 8.2

nother graph taken from Pension Trends shows the proportion of schemes in each

band of employee contribution rate. The trend has been up and it also shows that

at 6% and over you are probably in the sort of median area. And with another 3.2

ppts added on you will be among the highest contributors towards a salary

related scheme.

But, of course, the other side is that the employer also pays in – and the

employer is the council or local Government office you work for and that money

comes from taxpayers one way or another because the taxpayer is your employer.

And I know there is no fixed contribution – with 99 schemes and 9 of them in

Wales that would be too much to expect!

But

the important thing to recognise about the contributions is that you are buying

a very valuable pension. Now I know the average paid out is quite low. But that

is because pay is quite low, part-time working quite common, and working for

local government for a short time is not uncommon.

However, I learned two things yesterday from the Treasury – and they surprised

me but I have to take the word of the man I spoke to.

First, that the Government recognises the different circumstances of the LGPS

there are different issues and we would not rule out a different settlement. The

differences principally being of course that your schemes are funded – not

adequately and they have deficits but they are funded.

Second, the extra contributions from local Government workers are not part of

the £2.8bn the Government wants to raise and will go directly into the pension

schemes – not the Treasury.

So

you will pay more – exactly how much we do not know. But it will start from

April 2012.

The

two other changes – work longer and get less will not. They will start later

probably 2015 that’s the target date. And in the month they start you will

probably be voting in a General Election as that is fixed for 5 May 2015.

Work longer

Now

I am not going to rehearse the arguments for doing this. Though I have to say

life expectancy is growing by about 3 months every year that passes. And I do

think it is reasonable that pension age rises. The Government now says it wants

public sector pension age to rise with state pension age. And few things get as

many emails as that topic. Your pension scheme age is already 65 and so that

will not rise until after November 2018 when under the new timetable set out in

the Pensions Bill the state pension age for women reaches 65 and then it will

reach 66 by April 2020. After that it will rise further but we do not know when

that will start or finish.

That new pension age will only apply to the pension earned after the date the

change begins. So if the change begins in April 2015 all the pension earned

before that date can still be claimed at 65. All the pension earned after that

date cannot be claimed until you reach state pension age.

Get

less pension

The

final element is that the pension paid will, in many cases, be less than the one

you would get under the present scheme. And let me say at the start – that I

agree with this change.

It

will move all public sector pensions from their present structure where the

pension you get is a fraction of your salary at the time you reach pension age

(or leave the scheme) to one which is still based on your salary but is related

to your average salary over your time in the scheme.

And

I support that not because it will give some people lower pensions – though it

will – and it will give no-one higher pensions – but because it’s fairer. And

it’s fairer to the low paid and as that tends to be women fairer to them.

My

mind was changed on this by the interim report of the Hutton Independent Public

Service Pension Commission last year. John Hutton compared final salary schemes

with schemes where the pension is based on career average earnings. And noted

that high-flyers can get double the pension benefit from their pension

contributions than those who are not high flyers.

This analysis was not original. It used a paper from 2007 by Charles Sutcliffe

of the ICMA centre at Reading University.

He

found that a high flyer whose pay rose by 3.5% a year in real terms over a 40

year career would end up with pay of just over double that of a low flying

colleague who stayed in the same job for 40 years and gained no real rise in

pay.

But

because the pension was related to final salary, the pension earned by that pay

was not 2.02 times higher but 3.83 times higher. And that means that for each

pound he pays in, High Flying Henry earned nearly twice the pension that Low

Flying Louise earns for each pound she puts in.

Each £1000 of contributions Henry pays in buys him a pension of £178.24. Each

£1000 Louise pays in buys her just £94.18. That is a ratio of 1:1.89 – not quite

half as Hutton said but not far off. And you can devise scenarios which are even

worse.

Hutton gives the high flyer a woman’s name. And the low flyer a man’s. But that

isn’t the reality is it? We know that despite 40 years of equal pay laws women

earn less than men. We know that women have a lower chance of promotion than

men. We know that women are more likely to work part-time than men. And we know

that women get lower pensions than men. And those facts are of course all

related. So I have stuck with the sexist reality not embarked on the political

spin of women out-performing men – some do of course; but men conspire to stop

them when they can.

There are other inequalities. High flyers are more likely to be paying higher

rate tax – so their pensions are more heavily subsidised by the taxes paid by

others – including poor Louise of course. Every £1000 pound she pays in gets a

treasury contribution of £250. Every £1000 Henry pays in gets a Treasury

contribution of £667. That makes a big difference and on my calculation

increases the amount of pension earned for each £1 spent out of

net income from £1.89 to £2.52.

And

of course from this April when the 50% tax rate began on taxable income above

£150,000 a year the subsidy is even bigger for the very high flyers. Someone on

£250,000 salary who puts the new maximum of £50,000 into a pension will find it

is matched pound for pound by a generous Treasury – yes from the taxes of those

very people on £15,000 a year who probably have no pension scheme and no

personal pension either. And just to be clear: you earn £250,000, put £50,000

into a pension scheme out of your taxed income and George Osborne stumps up

another £50,000 in subsidy.

This slide is a bit out of date but it shows how the minority if higher rate

taxpayers get the bulk of the tax relief on pensions.

And

beyond that, Henry, being richer and living in a nicer neighbourhood is probably

going to live longer – if not than Louise because nature does take its revenge

at this point on men for their lifelong selfishness towards women – then

certainly longer than low flying Louis. The man in the back office who keeps his

low paid administrative job all his life.

So

Henry will get a bigger pension; get more per pound contributed; pay less for it

due to the bigger Treasury taxpayer subsidy; and draw it for longer than low

paid colleagues. No wonder he’s called Hooray Henry.

In

other words final salary schemes work by stealing money from low flyers and

giving it to their bosses. And I do not think that is right.

All

this assumes of course that Henry is promoted on merit. But you will know as

trustees that final salary pension schemes with surpluses have been used as a

way to get rid of difficult older staff, to free up the promotion ladder, or

just to give mega-rewards for friends of the directors.

Career average can end all those abuses. And that is why the civil service

pension scheme moved to it in 2008. At the moment the civil service scheme is

alone among public service pensions. But the Government has made it clear that

it will follow Lord Hutton’s recommendation in his final report to move all

schemes to career average.

But

the Government has also made it clear that any pension earned up until this

change begins – probably April 2015 – will be protected. And when you reach your

existing pension age 65 you will get a pension based on your accrued rights up

to April 2015 and a proportion of your final salary at the age of 65.

INFLATION

Inflation is the filling in the sandwich – one slice of pensions and another of

Government debt with inflation in the middle because it affects both

substantially.

Pensions are affected because the government has already from April this year

changed the way that public sector pensions are protected against inflation. It

changed the method of indexing from the Retail Prices Index to the Consumer

Prices Index. Now if you listen to Radio 4 bulletins you probably think you know

the difference between RPI and CPI. RPI is the one that includes housing costs.

That is what the news bulletins always say. I have tried to get it changed but

failed.

Now

it is true that RPI does include housing costs such as mortgage interest,

depreciation, and council tax. But that is not the main factor in the difference

between them. The main factor by

far is the formula effect – the difference in the maths how the index is worked

out.

At

the moment CPI is 4.5% and RPI 5.2% – a difference of 0.7%pts, normally

expressed as CPI-RPI. But that difference is not due to housing costs. Although

we take RPI and CPI to one dp in fact they are worked out to more. And the

difference between them is -0.74. That is made up of -0.09% due to housing costs

being in RPI but not in CPI, +0.16 due to coverage – the other items included.

+0.19 due to weights and other differences. And -1.00% due to the formula

effect. In other words if the formula effect was not there CPI would actually be

higher than RPI in May 5.5% not 4.5%.

At

the heart of the difference is mathematics. Each month 300 agents record 180,000

prices in 20,000 shops. They are turned into an average for the price of, say,

bananas. But just what is an average? In five shops a single banana costs 14p,

18p, 20p, 40p, and 63p.

The

RPI uses the simple arithmetic mean – you add up all the prices for bananas and

divide by however many there are. The RPI would call the average price 31p.

But the CPI does things differently. You

multiply all the prices together. And then take the nth root – where n is the

number of items. That gives what is called the geometric mean and that is –

26.3p.

That method takes account of the fact that if the price of bananas rises we buy

fewer of them – or we switch from organic to an own brand bunch. In other words

as inflation bites we try to keep the share of what we spend on bananas the

same.

And

the geometric mean is always less than or equal to the arithmetic mean. So CPI

is almost always lower than RPI. Which is why the Government prefers CPI when it

raises pensions or benefits. And chooses RPI when it comes to putting up the

duty we pay on petrol and alcohol.

And

the formula effect which was 1% in May is pretty constant now around that level.

So you can reckon that the CPI should pretty much be 1% higher if that

mathematical difference was not used.

It

may not seem much. But it makes a huge difference and of course is compounded

every year. The change will save £1.5bn this year, £3.05bn min 2012/13 and as

much as £10.595 billion in 2015/16. That is mainly benefits but a proportion of

that is public sector pensions.

The

Government has decided that private sector pensions can move to CPI if their

trust deed allows – and the minimum they must do set down by law is to be

changed to CPI – but they can if they wish move to RPI. In fact the effect is

limited because that is capped at 5% or 2.5% and that brings it below either

measure. So public sector is still lucky that it is given an uncapped increase

with inflation, albeit CPI now rather than RPI.

Inflation is not supposed to be 4.5% (5.2% if you go by RPI). In fact it is

supposed to be 2%. The Bank of England is supposed to control it to bring it

down to that level but it has been above its target for the last 18 months.

Normally inflation is controlled by raising or lowering interest rates. As the

Bank Rate rises the cost of borrowing rises and people and businesses are

inclined to borrow less and that slows down the economy and businesses can’t put

up price or have to cut them to encourage people to buy. So inflation falls.

Similarly when Bank Rate is cut that stimulates the economy and inflation tends

to rise.

That is the simple theory and the MPC for years had one lever to pull or push –

raising or lowering Bank Rate.

But

after the financial crisis of 2008 the most important thing was stimulating the

economy so interest rates were cut back and back to reach their lowest ever 0.5%

where they have been stuck for more than two years. And for fear of stopping the

rather halting economic growth the Bank dare not raise rates. So the one lever

it has to control inflation is denied it.

Worse than that, the Bank was worried that even 0.5% interest rates would not

get the economy growing. So in March 2009 it took another step called

Quantitative Easing. Also know as printing money. So far it has created, out of

nothing, £200 billion. That has not been printed – if it had the stack of notes

would be about 2000km high. But printing money to get out of a financial mess is

what one fund manager the other day called the economic policies of African

despots. But if you talk to normally rational economists they will now tell you

that QE will somehow not cause inflation – or not much anyway.

But

when the USA is also doing it and on a vastly bigger scale about $2 trillion so

far and a third round could be on the way – that affects us too. Oil and gold

and other more useful metals are priced in dollars. And if you just print more

dollars the price of this real stuff is bound to go up. So it is not just our QE

that is boosting inflation here, US QE is helping it along. And that is why the

Bank tells the Chancellor that rising commodity prices have pushed up prices

here and who could have predicted that? Well, anyone who knew that the US

Government was planning to print $2 trillion.

So

the Bank of England is failing in its key objective of controlling inflation.

And inflation is partly the reason why pensions – including public sector

pensions – are becoming more expensive.

And

of course we now know sort of officially what we have known for a long time.

That inflation in commodities – in real stuff particularly food and fuel –

affects low income households more. Because more of their money is spent on

those basics.

Inflation of course destroys the value of savings – with inflation at 5.2% money in the bank is worth less each year.

Here is what would happen to £1000 year by year. It halves in value – in terms

of what it will buy – in just 13 years. And then carries on of course – and you

can see by 2030 – after 20 years it is barely a third and of course that process

continues beyond the end of that slide. With inflation at 5.2% and interest

rates earned at little more than half that if you move your money every year

chasing good rates you cannot protect your savings against inflation still less

earn enough to give you an income.

DEBT

Now

the reason given for raising contributions to public sector pensions and to and

cutting the pensions you will earn is to save money. I mentioned earlier that

the switch from RPI to CPI will save more than £10bn a year by 2015/16. And the

increase in contributions is set to raise £2.8bn – excluding the contributions

paid by people in your schemes.

And

that and the many other cuts announced by the Coalition Government are designed

to close the gap between the Government’s annual income – which is basically all

the taxes we pay – from income tax and VAT to corporation tax and the duty on

alcohol. And the amount it spends each year.

That difference is the deficit – the amount we spend above what we earn each

year.

The

debt – the national debt – is the accumulation of all those past years of

deficit. So we overspend £146 billion this year and £122 billion next year we

owe another £268 billion. And in fact the total we owe is around £970 billion –

nearly a trillion.

That is our debt – that is if you like the nation’s credit card. And I will tell

you something that George Osborne doesn’t seem to know. We are not paying off

the nation’s credit card. Our debt

our credit card balance is growing.

All

that the Government is doing with all these cuts painful as they are is reducing

the amount we have to borrow each year. The Budget will not be in balance – ie

spending no more than we earn until 20xx on the Government forecasts.

Inflation part 2

And

that brings me to part 2 of inflation.

The

context is the complete failure of the Bank of England not just to control

inflation but to realise it was doing so. As part of its job the Bank does not

just decide on interest rates every month. Once every three months it produces a

report on inflation – why it is where it is and where it is going.

Let

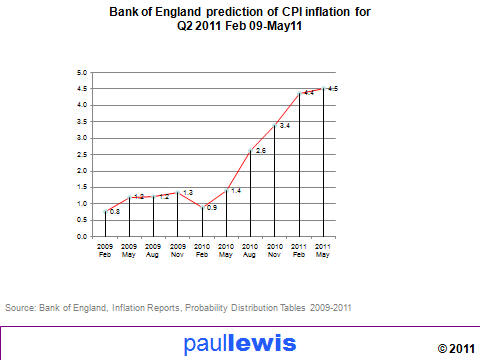

me show you a graph I did recently. I went back through these reports and looked

at where the bank said inflation would be today and where it in fact is.

This graph shows what the Bank predicted inflation would be now at various times

in the past. In Feb 2009 it thought we would have inflation now of 0.8%, that

rose over the next reports and then in Feb 10 the prediction for May 2011was

again 0.9. A year ago it still thought that now inflation would be 1.4%. Then it

rose with the next reports until in May this year it got inflation for May this

year about right. But just to reiterate, a year ago the Bank thought inflation

now today would be 1.4%. It is 4.5%.

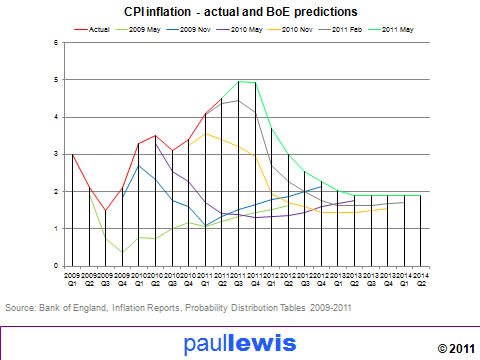

The next graph is a bit more complex. This red line shows

actual inflation from the first quarter of 2009 to this quarter Q2 of 2011.

Actual CPI inflation. So two years ago inflation was about 2% and the Bank

thought it would fall – light green line – and then rise gently towards its

target of 2%. It didn’t it rose. Three months later – blue line – the bank

predicted a fall. It rose again. A year ago the Bank predicted quite a sharp

fall – purple line – It did fall but soon rose sharply. At the end of last year

yellow line – Bank predicted a small rise then a fall. It rose and rose. Three

months ago ditto. And now the latest prediction that it will rise to about 5%

but then will fall sharply.

And

notice how every prediction has it hitting the 2% target in two years. And

notice how every single prediction has been wrong.

So

not only is the bank and its highly paid Monetary Policy Committee failing to

control inflation, it is also hopeless at predicting what it will be in future.

Perhaps the two are related.

I

said earlier that inflation destroys savings – if it is 5.2% a year £1000 is

only worth £500 in 13 years’ time. But it also destroys debt. And a debt of,

say, a trillion pounds will only be worth half a trillion in 13 years time. And

half again after a quarter of a century has passed. And there are some dreadful

cynics who think that the Government doesn’t really care if the Bank of England

fails to reach its inflation target. Because every year that inflation is high,

our national debt is worth less and is easier to control.

They call in evidence the letters written by the Governor of the Bank of England

to the Chancellor. That happens when inflation is amore than 1 percentage point

above its target – so with a target of 2% when inflation reaches 3.1% or more.

And then every third month that it remains there.

All

these letters are on the Bank of England website – I recommend them. The latest

– which is much like the other ten – goes like this.

Dear Chancellor, inflation is a bit higher than it should be because of

international pressures such as rising oil, food, and commodity prices and, by

the way, you did put up VAT and excise duties. If these price rises hadn’t

happened inflation would probably be lower. But I remain confident that within

our two year time horizon it will be back on target as these pressures naturally

fall out of the figures. Yours Mervyn.

Dear Governor, the Chancellor replies. Thank you for your letter. You certainly

have a difficult task and it is not my job to interfere in your independent

considerations. I am glad you are confident that inflation will fall to its

target in two years. Yours George.

Despite two years of abject failure the Bank of England Governor Mervyn King was

knighted earlier this month, for services to inflation no doubt. And when the

Queen touches his shoulder with the sword and says ‘Arise Sir Mervyn.’ will he

reply ‘Yes Ma’am but it will fall back in a couple of years…’

I’ll leave you on that thought.