This talk was given 21 June 2011

The text here may not be identical to the spoken text

Skeptics in the Pub - Leicester

WHY

CAN’T FINANCIAL ADVISERS GIVE REAL FINANCIAL ADVICE?

I’m

Paul Lewis a freelance financial journalist. Among other things I present Money

Box on Radio 4.

Just to be a bit formal I am not here representing any of my clients – Money

Box, Breakfast, Saga or God forbid the BBC. I am here as a freelance financial

journalist.

Financial Advisers – and why they can’t give financial advice.

I

am going to be sceptical in three ways tonight or rather about three things.

1.

The term ‘financial adviser’ breaks the Financial Services Authority rule that

statements to consumers must be fair, clear and not misleading.

2.

Most people do not need to invest or save and are better off without traditional

financial advice at all.

3.

The major changes due to start in January 2013 in what is called the Retail

Distribution Review which among other things are supposed to ban commission on

sales of financial products – they are not radical enough and may not work.

FINANCIAL ADVISER – fair, clear, and not misleading?

All

the information given to customers when financial products are sold has to be

fair, clear and not misleading. In some ways the term ‘financial adviser’ itself

is not fair, clear and no misleading.

Who

is a financial adviser by profession here?

Now. Keep your hands up those people who are professional financial advisers.

Here is a list of ten common financial topics I get asked about.

1.

Income tax

2.

Benefits

3.

National Insurance

4.

State pension

5.

Credit cards

6.

Current accounts

7.

Foreign currency

8.

Inheritance Tax

9.

Care home fees

10.

Fuel bills

Keep your hands up if you feel comfortable giving advice on those topics.

Let

me be more specific with ten common questions I might be asked.

1.

Income tax – is my tax code wrong?

2.

Benefits – what can a widow claim?

3.

National Insurance – Do I need to pay it on my earnings?

4.

State pension – how much will SERPS rise by this year?

5.

Credit cards – how do I cancel a regular payment I agreed to?

6.

Current accounts – which is the cheapest bank for an overdraft

7.

Foreign currency – where will I get the best rate for euros?

8.

Inheritance Tax – What allowance will my heirs get?

9.

Care home fees – does my daughter have to help with the cost?

10.

Fuel bills – how can I reduce the cost?

Those are all financial questions that need advice. Can any financial adviser

here answer them with confidence? Or even tell people where to go to get the

answers? And that is without mentioning debt, or budgeting, or student loans, or

tax credits, or cash savings…I could go on. So in what sense are you financial

advisers if you can’t give advice on basic questions about financial questions?

Now

if I had put this up

1.

Pensions

2.

Investment

and

probably

3.

Insurance

4.

Mortgages

your hands would have stayed up. And what do these four areas all have in

common? They all earn you commission. So it is not financial advice you give.

But pensions, investment, mortgage, and insurance advice because that’s how earn

your living. And most financial advisers earn a living through commission.

For

the last ten years I have been giving talks like this saying that commission was

the cancer at the heart of the financial services industry. I did discover that

was a bit of a false claim as the heart is the one organ in the human body that

is just about immune from cancer. But you get my drift. And over the years that

view has moved from being completely dismissed and derided – I’ve been jeered,

shouted at, abused, buttonholed, people have even walked out – but now they are

mainstream as the FSA has slowly come round to my view on this as on many other

things – such as regulating products not processes.

And

commission is wrong because when I sit opposite someone who is recommending me

to invest my money in a product I don’t really understand and which will cost me

money every year regardless of whether it does what it should do or not, I want

to know why is that person recommending that to me? Is it because it is best for

me? Or best for them?

And

that conflict of interest lies at the heart of the problems of the financial

services industry. A conflict of interest does not mean someone deliberately

sells a rubbish product just to earn the commission. Undoubtedly some have. But

most don’t.

My

uncle was an IFA and he is the kindest, fairest, and, if it matters, most

Christian man you could imagine. I don’t believe for one moment he sold me an

endowment mortgage just because of the commission he earned on it. He genuinely

believed it was a good idea. He had been told so by those clever people at

Standard Life who manufactured it and surely knew what they were talking about.

They had actuaries and everything. So it was win/win – by selling me the right

thing, he earned money.

The

insurers who made that crazy product promoted it through high rates of

commission because it was so profitable. It matched two incompatible things. The

mortgage was interest only – so the capital was not paid off. Parallel with that

was sold an investment – the endowment – and that was supposed to produce a

return big enough to pay off the mortgage and give a bit extra on top. And it

cost no more. Magic.

The

fact it was and always would be a mis-match – an uncertain investment to meet a

fixed and certain debt – was ignored. Not by good honest salesmen like my uncle.

But by the people who devised it and sold the idea to him and gave him a cash

incentive to sell it.

Mortgage endowments sold from the 1980s right up to the late 1990s left up to

five million people up to £40 billion short of the money they need to repay

their mortgage. Nearly £3 billion of compensation has been paid.

I

could go on – AVCs, SERPS opt-outs, precipice bonds, split capital investment

trusts, structured products – no lawful industry has been rocked by such a

succession of scandals. And all of them can be traced back to commission.

I

am sometimes asked what can the financial services industry do to regain the

public’s trust? And my answer is ‘when did it have the public’s trust?

Today’s industry has been around for only 25 years.

Twenty five years ago the past was indeed a foreign country.

Nigel Lawson, Chancellor of the Exchequer. Margaret Thatcher was Prime Minister.

And Norman Fowler, now sunk into obscurity, was S of S for Pensions.

And

in this foreign land called ‘the mid 1980s’ there were no personal pensions. And

there was no financial services industry as we understand it. There was the man

from the Pru and there were stockbrokers, and that was about it.

The

Thatcher Government came up with the idea that we should cast off the chains of

Government dependency. Official adverts showed a chained man setting himself

free. And the first thing he did, as you would after a long time in chains, he

bought himself a pension. One of the new personal pensions.

And for those who took responsibility

for themselves there was, without any irony, a useful taxpayer subsidy. Around

8% of your pay.

But

Margaret Thatcher made an even more important change. Before 6 April 1988 if

there was a pension scheme at your job you had to join it – no choice. Margaret

Thatcher ended that. Three weeks later (28 April) the first personal pensions

went on sale.

This was the moment when the financial services industry could have grown and

developed into a popular, useful, worthwhile, and much loved business. Instead

it sent teams of poorly trained, commission driven sales staff to descend on a

hapless population who believed the adverts and newspaper stories which said

that for a few pounds a month everyone could buy political AND financial

independence.

Altogether the industry systematically mis-sold the new personal pensions to

millions of people keen to embrace the new world of freedom from the state and

personal responsibility. They were persuaded to leave good company schemes and

put their money at risk in personal pension plans. More than a decade later the

industry admitted its mistake and forked out £11.5bn in compensation plus

another £2bn to find and deliver the money to the two million people known to

have been mis-sold.

There were all sorts of things that contributed to that systematic mis-selling –

Government adverts, political interference, phrases like ‘personal

responsibility’, and articles by compliant newspaper columnists with little

understanding of risk or indeed of pensions– but the fuel which drove it to the

heights it achieved was commission.

It

is commission – not solutions to financial problems – which has driven the

growth in the financial services industry.

And

this isn’t just historical stuff.

In

January this year Hector Sants, Chief Executive of the FSA, told MPs that mis-selling

still cost the public up to £600 million a year. He gave one example – the FSA’s

2008 review of what is called pension switching – moving your pension from one

provider – like Axa – to another – like Standard Life. It looked at IFAs, and

variously tied advisers and the FSA judged that 16 per cent – one in every six –

sales were unsuitable. This one category of mis-selling cost consumers £43m a

year.

The

image even of Financial Advisers has become so bad that many IFAs have tried to

rebrand themselves – sometimes as financial planners, and for the top end, as

wealth managers. But beware if you are wealthy enough to employ a wealth

manager. The FSA recently reviewed the files of 16 wealth managers. And things

were so bad it felt obliged to write to the Chief Executives of all similar

firms.

It’s called a ‘Dear CEO’ letter and this one, dated a week ago demands immediate

attention and says it has found significant and widespread failings and that

·

14/16 firms posed a high or medium risk to their customers

·

Nearly four out of five files (79%) showed a high risk of being unsuitable

·

Two

out of three (67%) weren’t consistent with the client’s attitude to risk or

investment objectives.

14/16 of a sample of wealth managers were putting the money of most of their

clients at an unsuitable risk. Wealthy clients. In 2011.

And

that is why financial advisers have been seen as commission-driven sales staff,

mis-selling financial products to a hapless and largely ignorant population. And

that is why the Financial Services Authority has decided that commission has to

go – at least so far as pensions and investments are concerned. Because it

biases the sales process and gives the adviser a different interest from that of

their client.

And

that applies even to the majority of IFAs who genuinely want to help us take

personal responsibility and save for our future.

When there was a discussion some years ago about financial advice I asked the

FSA if the very name financial adviser could be changed. Yes, I was told, maybe.

And I suggested ‘commission driven sales staff’. It didn’t happen.

There are to be big changes – and we’ll come onto those in part three. Now for

part 2.

2.

DO WE NEED FINANCIAL ADVICE?

Language is often used to disguise things. I was asked recently to talk about

what ‘retirement solutions’. And I began by quibbling over the phrase

‘retirement solutions’. A solution has to be the answer to a problem. And what

problem do people have about retirement?

Bill Deedes, at one time editor of The

Daily Telegraph and before that a Cabinet minister, born in 1913 who died at

the age of 94 in 2007 had a very neat solution to retirement – he didn’t do it.

During his final illness he wrote his Telegraph columns on his laptop in bed.

His final column was published just two weeks before he died – on Darfur being

as bad as Nazi Germany (he had been to both). His family reported that he was

writing another column as he died. And for myself that would be my wish – found

in bed with my laptop open and a half finished piece on the screen. To die doing

my job, earning my living. Not at the tedious end of a 30 year holiday paid for

by other people.

It’s a small example of how the industry uses words not to enlighten but

deceive. By calling it retirement

solutions you beg the question is there a problem in the first place? Maybe

there isn’t. And you may say well yes the problem is that most people don’t have

enough income in retirement. Which is true. But many of them won’t have had

enough income in their lives generally. And there is no reason to believe that

saving for a pension will solve that problem for them. Not having enough money

is the default state at any age for most of us.

At

least half the population has debt – not mortgages though that is also present –

but personal debt – credit cards with a balance running, personal loans, money

borrowed for a car, a kitchen, a holiday, and nowadays perhaps a payday loan –

smaller short-term loans at APRs in the thousands. Or of course a persistent

overdraft – with an APR sometimes in the millions – I won’t go into that here.

The Bank of England puts the total at £211 billion of consumer credit. That is

about £7,700 per UK household (27.5mn in UK). Except that probably around half

of households do not owe anything – those figures are a bit flaky. But if that

is true it means that each household in debt owes around £15,000. Suppose they

are paying interest of 10% on that – very modest – that is £1500 a year, or £125

out of every monthly household pay packet – just on servicing that debt without

repaying a penny of it. And that is without the almost £1.25 trillion debt

secured on our homes through mortgages and second mortgages.

So

if someone goes to an Independent Financial Adviser the first question should be

– do you have personal debt? And if the answer is ‘yes’ then the IFA should say

–‘Thanks for coming to see me. But pay off your debt and then come back. There

is no point in having a debt that costs you 9% or 19% or 1900% a year and saving

or investing money that will earn you 3% or even 7% or 9% a year as some

investments aspire to. Spare money should be used to pay off debts first. The

only two possible exceptions are student loans where interest rates are set at

the rate of RPI inflation or in some cases at Bank Rate plus 1% = 1.5%. And some

mortgages which are very cheap at the moment. 2% or 3%.

But

otherwise generally pay off debt rather than save.

Another mistake advisers often make is to confuse saving and investing. They are

not the same thing. And it’s not just advisers who get it wrong. Ask Her

Majesty’s Treasury the difference and it will call a shares based ISA a ‘savings

account’ and those with them as ‘savers’. But there is one very simple

difference between saving and investing.

If

you save, your money remains yours.

If

you invest, your money belongs to someone else.

It

is that simple.

Suppose you have £500 to spare.

You

go to the bank and put it into a savings account. The £500 remains yours. You

have lent it to the bank. A year later, you need the money back. You go along to

the bank and take it out and, hey, the bank has added £15. It takes off £3 tax

which leaves you with a profit of £12. And you have done no work! Magic!

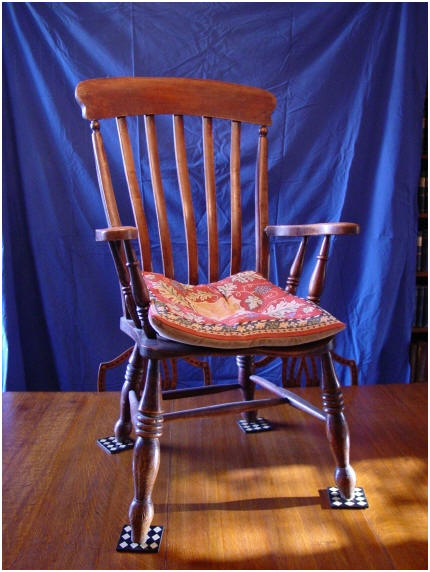

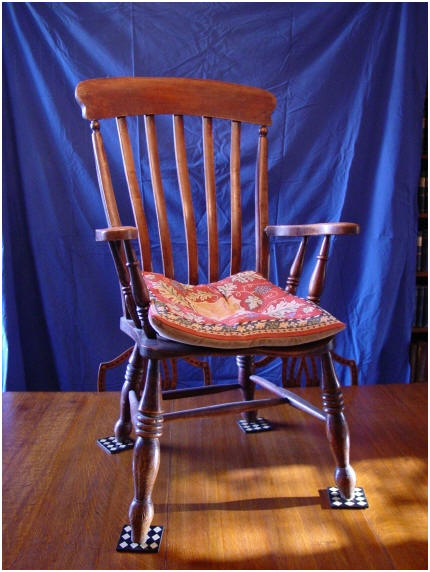

Alternatively you invest it. You go to Mr Oldenshaw’s antique shop. You see a

really nice antique chair for £550. You bargain with Mr Oldenshaw and hand

over£500 in tenners. He gives you the chair.

You

take it home and you sit on it - carefully. A year later, you need the money

back. You can’t take the chair to the bank and cash it in. You have to sell it.

So you take it back to Mr Oldenshaw. But now Mr O, who really loved that chair

and told you how rare a chair of that age was, especially in that condition, now

says the market for brown chairs has really dried up recently and the most he

can give you is £200. And that is cutting his own throat. You invested £500 you

get £200. Loss £300.

That’s the difference between investing and saving. Many people think that,

because many things called ‘investments’ involve money rather than old

furniture, the money they use to buy them is still somehow ‘theirs’. It is not.

Just like when you buy a chair. The money is someone else’s. The investment is

yours. To get your money back someone has to buy it from you, at the right

price, when you want to sell it.

How

many financial advisers make that clear distinction – do you want to save or

invest? And if you invest you may not get your money back. It is that simple.

And

that brings us of course to risk. Risk simply means that there can be a happy

ending and a sad ending. And often the difference between them is out of your

hands.

I

still hear financial advisers say “Well normally risk provides reward, so over

the longer period of time you would expect the stock market, which obviously is

the highest risk, to provide you the highest returns.” That’s a direct quote

from a well-known IFA on an even better known Radio 4 programme in February

2005.

‘Risk provides reward’ No it doesn’t. If taking a risk meant you got a reward it

wouldn’t be a risk would it? Risk means you can lose money. Oddly, the other way

round it is true. If you want a bigger return you have to take a risk. But the

risk is you won’t get the higher return – you will get a much lower one .

And

assessing what the industry calls customers’ ‘attitude to risk’ is not done

well. Because most people haven’t got a clue. What’s your attitude to risk?

‘Well, I do the Lottery, I like a flutter. I take a chance now and then.’

‘I’ll put you down as balanced but erring on the adventurous side then?’

‘Yeah OK’.

Poor assessment of risk is endemic in financial services. In January this year

the FSA produced a report. It examined files across the financial services

industry between March 2008 and September 2010 – two and a half years. The

advisers did not do well. It assessed that half those files showed unsuitable

advice was given because the investment selection failed to meet the risk a

customer was willing and able to take.

Here is how I would assess attitude to risk. I would ask this

‘You’ve got £1000. You follow my advice and invest in this product. In a year’s

time it’s worth £600. How will you feel?’ What do they say?

·

Terrible – I worked hard for that money and I did not want it lost to someone

else.

Savings account person

·

Quite happy – I knew I could lose it but I also knew there was a chance I could

make more than I could in a savings account. It was a bet. I lost. Some you win,

some you lose.

Perfect stock market investor

·

A

bit upset – I was told it was a risk but I did not really expect to lose money.

You don’t do you?

Most people

Risk means you can lose your money. But many advisers don’t explain that

clearly.

Now

I have been critical of independent financial advisers so let’s redress the

balance a bit and talk about the other category of person who is still allowed

to be called a financial adviser – but is not.

I

mean the people who work in banks. Technical they are what are currently called

‘tied agents’. In other words although they sell financial products they can

only sell you stuff from one provider – normally their own bank or an insurance

company they have a deal with. For example Barclays used to be tied to Aviva for

investment products. So its advisers could only sell those products.

So

these people cannot possibly give you good advice. They can only sell you

products from one provider out of hundreds. The best advice for most products

will be – don’t buy from me go down the road and buy from another company that

offers a better deal. But they not only do not do that they are not allowed to

do that.

So

never, ever, ever go to your bank for financial advice. Because it is rubbish.

And it is even more commission driven than it is in the IFA sector.

Barclays is one of our biggest banks, and one that more than a million people

trust to give them investment or pensions advice. In January this year the

Financial Services Authority fined Barclays Bank £7.7 million for mis-selling

two funds called ‘cautious’ and ‘balanced’ which were anything but. It sold them

for more than two years to more than 12,000 people who invested nearly £700 mn.

The FSA found that Barclays failed

·

to

ensure the funds were suitable for customers in view of their investment

objectives, financial circumstances, investment knowledge and experience;

·

to

ensure that training given to sales staff adequately explained the risks

associated with the funds;

·

to

ensure product brochures and other documents given to customers clearly

explained the risks involved and could not mislead customers; and

In

addition to its £7.7mn fine Barclays could pay a total of £60mn in compensation.

And this mis-selling to more than 8,000 people was not just down to

over-enthusiastic sales people. Barclays put out training material that was

simply misleading to them as well.

People who thought they were being sold a cautious investment saw it fall 30%,

those with a balanced investment lost 50%. Many – afraid of what they saw – sold

at just the wrong time. Of course if they hang on things might bet better but

more than half the money has been pulled out. Also shows they did not understand

much about stock market investments.

Why

did Barclays sell this fund? Because Aviva paid it 4.5% of the money invested

and then 1% a year thereafter – money that came from the investors’ money.

Within a fortnight of the bank being fined £7.7mn it decided to stop selling

investment advice in its branches.

So

investment is a risk. And I showed you the sad ending with the chair. But there

is a happy alternative. You take it to Chairstyle, a specialist dealer. Miss

Carver takes one look at it and her eyes light up. She has just the customer who

needs your chair to make a nice mixed set of six.

So

risk goes both ways. Put it in the bank and there’s no risk – you know you will

make a small amount of money. Buy a chair and there is a chance you will make a

lot more money than you would in the bank. But there is also the chance you will

lose money. That is what risk means. You gamble the chance of making more money

against the chance of losing some – or exceptionally all – of the money you

invested.

And

remember a financial investment is just a chair. With the further downside that

you are paying someone to store it for you and they will charge you every single

day and regardless of whether it goes up or down in value.

But

advisers have an answer for that analysis too, They say there

is a risk in putting the money in

the bank. In ten years’ time it may not have kept up with inflation. You’ll have

less than when you started.’ And today with even the best interest rates around

3% taxable so worth 2.4% to a basic rate taxpayer. Yet inflation is 5.2% in May

(4.5% on CPI) and rising. So money in the bank won’t even keep up with inflation

never mind provide you with an income.

That’s what the arithmetic shows. But it is not an argument for investing rather

than saving.

I

was interviewing someone who runs a major financial services company about the

risk of putting money in shares. And he said – I paraphrase – ‘the real risk is

putting it in a cash savings account. And ten years later it is worth less than

you put in because of inflation. That’s the really risky option.’

Of

course there is the possibility that inflation will have exceeded returns on

deposit accounts. But over that period of time you have to discount the same

amount for inflation whatever you do with your money. So there is no particular

‘risk’ that affects a deposit account. It is just inflation. And if you put it

in shares, or Greek bonds, or you buy gold it may not keep up with inflation

either. It is just sloppy thinking used to confuse people. To try to make them

feel that deposit accounts carry some sort of ‘risk’ which is the same as the

‘risk’ which attaches to share based investments. It is not true. It

is misleading.

As

I said earlier financial firms are supposed to treat their customers fairly and

provide information and advice which is true, fair and not misleading. That way

of dealing with risk and cash savings is none of those things.

And

of course there is now a savings product that does keep up with inflation and a

little bit more NS&I index linked certificates which pay RPI which will probably

be 3.5% or more for the next four years.

plus 0.25% if you cash them in after a year and RPI + 0.5% a year if you wait

for five years.

Tax

free.

Max

of £15,000 but anyone going to a financial adviser with less than that should be

told put it in there – no other product can offer that guarantee. Backed by the

Government – and not Greek government.

But

do many IFAs recommend that to all their customers who come in with £15k or

less? I wonder.

3.

Retail Distribution Reveiw

Let

me come on to part three of this sceptical talk. Because we are meeting tonight

at a time of immense, tremendous change in the financial services industry.

First, there is the abolition of the Financial Services Authority – or rather

its transmogrification into the Financial Conduct Authority. And that is more

than just changing one word. It will get new powers. Powers that I have been

calling for years.

Power to regulate and even ban products before they go on sale. Until recently

the FSA could only regulate how things were sold not what was sold. Slowly that

has changed.

The

power to tell us which companies they were investigating. At the moment they can

do mystery shopping, find out that 14 out of 16 wealth managers are mis-selling

their rich clients investment products but cannot legally tell us which 14 they

are – and indeed which two they are not.

And

finally it will be able to crack down quickly on misleading advertisements. At

the moment it refuses – and says it can’t – name adverts it is concerned about.

Whether it will have the same powers as the ASA remains to be seen. But these

three new powers should help consumers hugely.

And, dare I say, like banning commission, three things I have specifically

called for many times.

Not

sure when the FCA will take over from the FSA but it will probably be around the

end of 2012. Eighteen months away. And that is the same time that other huge

changes will be made by the Retail Distribution Review – RDR – from January

2013. It is intended to change fundamentally the way pensions and investments

are sold. Or at least it should change the way the people who sell them are

paid. And that should change the nature of the job of financial advice

fundamentally. But, you won’t be surprised to hear, that I am becoming more and

more sceptical about the RDR and the end of commission. And if I am right then

the past sadly may very well be a guide to the future.

I

was at a conference the other day for more than 100 IFAs. Like most conferences

of IFAs it is the good guys who go there. The ones who want to do a good job,

serve their clients and earn a living. They are not the ones who think Ethics is

a county to the east of London. And many of them buttonholed me after I had done

my presentation and said they were already what they called RDR compliant –

their business already behaves as if the Retail Distribution Review was in

force.

But

the more I spoke to them the more worried I got. My sense of a professional

relationship with an adviser – an accountant or a lawyer – is this. I make an

appointment, go to their office, get my advice, agree a fee, they do some legal

or accountancy work for me, and they send me a bill for their work, say £600,

and I pay the bill. If I can’t pay it at once I use a credit card and spread the

payments.

Naively I had thought that under the RDR something similar would happen. I would

visit my IFA, he or she would say to meet your objectives you need to put £150 a

month into a pension. I will research and find the best pension for you. That

will cost you £1000. I will review your circumstances and that will cost you £20

a month. I would go away and when I took out the pension I would get out my

credit card and pay the IFA £1000 and take out a standing order for £20 a month

to pay for ongoing review.

No.

It will not work like that. I will simply pay £150 a month. The £20 ongoing fee

will come out of that first leaving £130 and that balance will be used first to

pay the £1000 fee. So it is not until month eight that a penny goes into my

pension. And thereafter I pay £150

but only £130 goes towards my retirement.

Now

because those fees will be set by the IFA and would be the same whichever

pension provider was chosen, commission – and the conflict of interest and

potential bias that are part of it – is said to be gone. The Financial Services

Authority tells me that this arrangement that I have set out is completely

different. It is just what it calls a ‘payment mechanism’ not commission and

would be clearly agreed with the IFA beforehand. But it looks and feels like

commission to me.

It

is true the bias has gone – that £1000 would be set by the IFA and they would be

paid that much whether they recommended Aviva or Axa or Scottish Widows or

Standard Life. And the £20 a month ongoing fee would not just be what is called

trail commission – a sort of gravy train for life. The adviser would have to

work for that £240 a year – a good hour’s work once a year on the anniversary to

send a computer generated report and a letter. But again. It feels rather like

what was called ‘trail commission’ a payment from the pension firm to the IFA

every year that the policy continued.

And many investors are going to forget just what their IFA should be doing for

their money. But if you got a bill every year for £240 you might be far more

likely to say – hang on a minute, what’s that for?

And

it could be worse than that. Instead of creaming off the first £20 and passing

it onto your adviser, it could accept the whole lot and then cash in your units.

Now that will incur all sorts of other costs – I won’t go into the iniquity of

costs charged by pension funds themselves. And my view is that good advice will

always be to pick the fund that charges the least. But that’s another debate.

These figures are just examples – some will be worse some a lot better. But it

will damage your pension fund. On these numbers it will mean 15% a year less in

it even if you keep it for 40 years. But most people do not. Over four years it

means that 27% of your investment disappears in charges. Why four years? I will

explain.

Persistency

Every Autumn the FSA publishes a little noticed report called Survey of the

Persistency of Life and Pensions Policies. The series was due to be axed in 2007

but after the then chairman Callum McCarthy said poor persistency was evidence

for how the market was not working it was reprieved.

There are a lot of figures in this report let me concentrate just on pensions

and

on two sets of figures.

The

first set show show how many personal pensions taken out are still live after 1,

2, 3, and 4 years. The latest year we have four year figures for are policies

sold in 2005 and how many were still in force in 2006, 2007, 2008, 2009.

Here is how they change year by year. After one year 81.5%, after 2 yrs 66%, two

out of three, after 3 years just over half and after four years 44%. In other

words after four years most personal pensions sold by IFAs 56% have been

abandoned.

And

the figures are even worse for personal pensions sold by company representatives

– ie tied advisers. Only 41% in force – so nearly 6/10 are abandoned.

And

there are two more damning things about theses figures. Over time the record of

persistency has got worse.

These figures show the persistency after four years of pensions sold each year

since 1993 to 2005. Pensions sold by company representatives have declined from

57% to about 41%. In the case of IFAs persistency has declined from 70% of 1993

pensions to 44% for those sold in 2005.

The

report says:

“If

investors buy policies on the basis of good advice, they would not normally be

expected to give them up.” (para 3.3).

I

was strongly challenged on these figures by an IFA at a conference recently. She

told me that the reason so many were given up was simple. Many personal pensions

– a growing number – were in group personal pensions. These are a form a company

sponsored scheme which enters staff into personal pensions, individual pensions,

but perhaps contributed to by the employer and when you leave the job, you would

normally leave the scheme. It’s a plausible explanation. And certainly changing

circumstances are the main reason given for giving up a pension.

But

the figures show that does not really explain the fall. The FSA research also

separates the figures for personal pensions into those joined through a company

scheme and those joined through a company group scheme. Data not complete for

three years but the evidence is clear. The red line is IFAs combined. Green is

Group and purple is Individual. So although group are worse – for the reason

that people leave their scheme when they leave their job – it is still bad for

individuals. Now flat after worsening for some time.

So

if more than half are giving up these long-term, life-time products within four

years we can conclude that something is going wrong. Is it mis-selling, mis-buying,

or just misunderstanding?

Whatever it is, it is not good financial advice.

And

will the end of commission make it better? We will have to see.

In

fact we will have to see if it will even be the end of commission.

Apart from my concerns about pseudo commission through the payment mechanism –

the RDR does not extend to insurance. And many IFAs unable to end the dependency

on commission will sell more insurance alongside investments. And commission

there that can remain secret. And worse than that there are – and will be – many

IFAs who will be independent for investment and pensions advice but will be tied

to one insurance company so cannot give ‘insurance advice’ in any meaningful

way. And they will also be incentivised as they like to cal lit to sell

insurance that may – or may not – be a good idea.

So

to sum up.

Do

financial advisers really give the financial advice we need? Not often.

So

we all need to see a financial adviser? Absolutely not.

Will the Retail Distribution Review make things better? Yes. But there is still

a long way to go.

Thank you.