This talk was given 15 March 2011

The text here may not be identical to the spoken text

FAIR AND ADEQUATE PENSIONS

INTRODUCTION

I’m

Paul Lewis. I am a freelance financial journalist. I present Money Box and Money

Box Live on Radio 4. And I do spots on Saturday and Thursday on Breakfast on

BBC1.

The

BBC is just one of my clients. I also write two columns a month for

Saga Magazine which some of you may

see – I know, at your mum’s or at the doctor’s. And I have just written my first

piece for The Oldie.

Ageing is a sad business.

As

a freelance journalist, writer and broadcaster, I am not here representing any

of my clients and in particular, because they get very antsy about it, not

representing Money Box or, God forbid, the BBC.

So

any views I express are mine and mine alone. You can read a selection of them

and what I do on my website. And now you can keep up with them 24 hours a day

through my twitter @paullewismoney – and see what I look like some years ago.

Well it was the only photograph I had to hand. Olympics ticketing problems is

the trending topic today

I

eventually decided to call my talk to you today

FAIR AND ADEQUATE PENSIONS. I toyed

with the idea of a question mark after it but I hate that kind of hedging your

bets.

So

what is a fair and adequate pension? And how do we achieve one?

Final salary schemes have always been held up as the example of fair and

adequate pensions. They are certainly seen as

fair by employees but many of them

do not consider them adequate

judging by the emails I have been getting recently from people in public sector

schemes. The median pension is less than £5,600, about the same as the state

pension, so not huge.

But

the real reason they are so liked is because they give three simple things. A

known level of contributions. A guaranteed level of pension. And at a known age.

So

you pay in your 5.5-7.5% or 6.4% of

your monthly pay – before tax – and for every year you pay into the scheme you

get 1/80th or 1/60th of your salary at retirement. So if

you devote your working life to public service you can retire on half or two

thirds of your pay when you retire, for the rest of your life, and protected

fully against inflation.

Who

wouldn’t want a pension like that?

The

problem is that what happens between those monthly contributions in work and

that monthly pension in retirement was just a black box, surrounded by mist, and

filled with magic.

Arthur C Clarke said in 1973 that any sufficiently advanced technology is

indistinguishable from magic. Just as we use our mobile phone but haven’t got a

clue how it works so no-one really wondered how their pension worked. It did. We

ignored the mechanism that drove our pension plan.

And

all the time that such pensions were the standard in the private sector – where

a pension existed at all – and while it was accepted that people in the public

sector earned less than those in the private sector – then these good public

sector pensions were accepted and rumbled on without much comment. Even the

details of how they worked, the level of contributions, the benefits earned were

actually quite difficult to find.

But

now that private sector pensions are being closed down at a record rate – 17pc

now shut even to existing members. Now that fewer and fewer people have access

to them outside the public sector. All the details are being pored over for an

advantage or disadvantage here or there the same pressures that are causing the

flight from final salary in the private sector are being mapped across to the

public sector.

AFFORDABILITY

Affordability is the first of these pressures. When Lord Hutton’s report came

out on Thursday I was asked on BBC Breakfast if it was true that we couldn’t

afford public sector pensions. I said ‘No, it’s not. We can afford them. We are

choosing not to’.

Remember that there have already been many changes to public sector pensions.

Between 2005-2008 all the main schemes that Hutton was concerned with have

changed including the teacher’s Pension Scheme and the Local Government Pension

Scheme paid in colleges. Contributions went up, pension age went up, though

accrual rates got better for new members.

Then in the Budget last June the Chancellor announced that he would change the

indexation from RPI to CPI. A huge change that will save billions every year –

nearly £6bn in 2014-15 – mostly from those on state benefits but about £1.3bn of

that from public sector pensions.

So

after that can we afford them? So I turned to the Hutton report and there it is

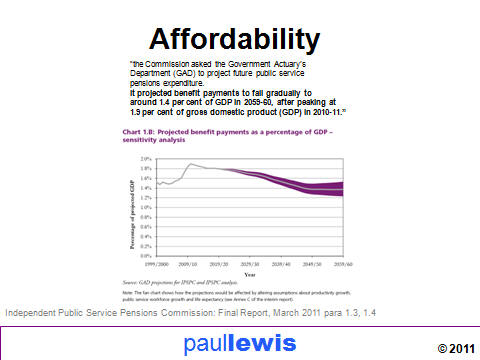

on p.22

“the Commission asked the Government Actuary’s

So

now they cost us 1.9% of GDP of our national income. And over the next fifty

years that cost will fall steadily and reach 1.4% in 2059/60.

When I asked Lord Hutton about that on Money Box on Saturday he said that such

projections were ‘difficult to model’ and don’t ‘bet your shirt’ on them being

right – be prudent.

But

that prediction was made by the Government Actuary – no less – and took this

uncertainty into account.

Here is his graph – from Hutton – reflecting that uncertainty. It shows that

even the most pessimistic assumptions give a cost in 2059/60 which is less than

it is now as a percentage of our national income.

And

this graph was done before the

Government decided to raise the contributions paid by members by around three

percentage points.

I

take the simple view that if we can afford the cost now we can afford it in the

future. And that’s not just my view. It was confirmed in a conversation I had

with the new Director of the Institute for Fiscal Studies Paul Johnson last

week. In an email he said to me

“Yes

these pensions are “affordable” … if that’s what government decided it wanted to

spend its money on.

So

it is not about affordability at all. It is about what we choose to spend our

money on. And it comes down to the fairness issue that I mentioned earlier. If

final salary schemes are disappearing throughout the private sector, if the

Government is compelling employers through auto-enrolment to introduce a scheme

with low contributions and no guarantees, is it fair to give final salary to

people in the public sector when the cost and the risk is borne by taxpayers?

So

that leads to the question – why are final salary pensions disappearing in the

private sector?

My

belief is they never could work as people believed they worked. And that as soon

as the mechanism was looked at, it was fiddled with and that stopped it working.

Let’s look first at what the politicians did to wreck them.

CONTRIBUTION HOLIDAYS

As

you may know the BBC is currently planning big cuts in the pension scheme. As a

freelance I am just an interested bystander I am not allowed in the BBC scheme –

which is why I’m still working. But one big complaint made by colleagues was

that the BBC had taken a contribution holiday, not paid into the scheme, for 15

years. If it hadn’t enjoyed that holiday, the unions say, it would not be in

this mess now. It’s a common view. Is it true?

When Nigel Lawson was Chancellor of the Exchequer in the 1980s he was very

concerned that companies were using pension funds as a means of salting money

away tax free and then taking it back out later. So he introduced a rule that if

a pension scheme had funds which were worth more than 105% of what the actuaries

said it needed to meet its pension promises, then that surplus could be taxed.

So companies scrambled to reduce the surplus in their scheme. The most popular

means of doing that was to reduce the amount they paid in. What we now call a

contributions holiday. But there were other techniques. You could enhance the

benefits paid to scheme members or you could cut the contributions paid by those

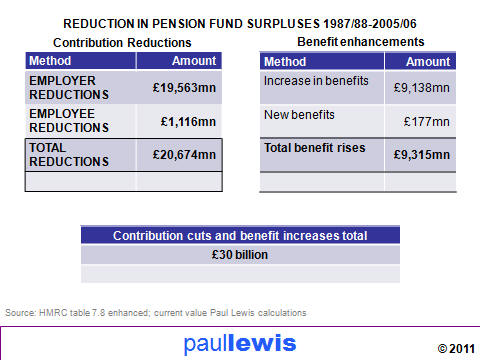

still paying in. Here are the total amounts employers took out – or stopped

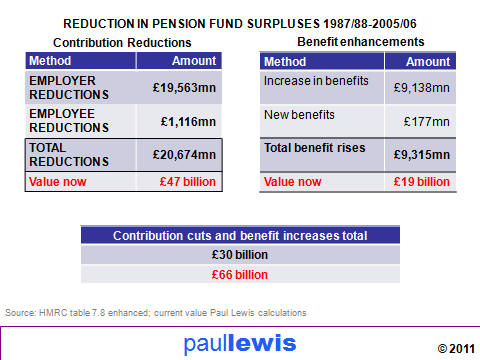

paying into – their pension funds from 1987 to 2006.

Over those 19 years employers took almost £20 billion out of pension schemes,

employees benefited from cuts in their contributions worth about £1 billion and

were treated to enhanced benefits

to the tune of around £9bn. So £21bn taken out and £9bn of future commitments

added. Though as you can see almost all the contribution cuts benefited the

employer. And the total is almost £30 billion taken out or given away in better

benefits.

But

these are historic cash figures. Between 1987 and 2000 the value of shares rose

strongly. The FTSE 100 index – and I use that as a proxy for investment growth

to illustrate my point – grew by a compound rate of 4.55% from 1987 when the

surpluses were first reduced to the end of last year.

Most of these surpluses were taken out in the early years. And my latest

calculation indicates that if those holidays had never been taken and those

benefits had never been enhanced it would mean an extra £66 billion in pension

funds today.

And

those £9 billion worth of enhanced benefits mean more costs further down the

track. So not only was less going in but future commitments were piling up.

Contribution holidays and benefit enhancements – all consequences of Lawson’s

Law – have played a big part in the problems final salary schemes face today.

I

will pass more quickly over the more familiar pensions raid by Gordon Brown. But

the total cost to pension funds and others of the change to the tax on dividends

was £5.4 billion in the first year. However, estimates by the Pension Policy

Institute calculated that the true cost to pension funds was much less – between

£2.5 and £3.5 billion a year, and that figure reduces over time. Today so many

other changes have happened that it is impossible to put the clock back and see

what if it had never happened. But it was certainly less than the potential

shortfall in those funds caused by Lawson’s Law. And between them? Anything up

to £100bn off the current value of pension funds.

Both these raids were made because politicians saw the funds as too successful.

They had too much money. The schemes can’t work well because of political

interference.

There is a second unacknowledged reason why final salary schemes can’t survive

in their present form.

FAIRNESS

The

mid 1970s on to the end of the 20th century is seen as the Golden Age

of Pensions. Good company schemes were affordable, reliable and secure;

investment returns were good.

And

final salary pension schemes stole money from people who left before they

retired.

Remember that at the start of the Golden Age if there was a pension scheme you

had to join it. So everyone who worked for one of these top companies was

automatically enrolled in the pension scheme willy nilly, however long they

planned to work for the company and whatever their personal circumstances.

Until 1975 if you left the company you also left the pension scheme and you got

nothing. Or almost. The contributions you had made were refunded – minus tax

because you had made them out of tax-free income so the Revenue took that back.

But the fund kept the growth on those contributions. And it kept the

contributions paid in by your employer – which were always more than you had put

in. And it kept the growth on those too. So those who stayed in the scheme stole

most of the contributions and all of the growth from those early leavers.

Over the next three decades that unfairness was removed piece by piece.

From April 1975 if you left the job you could leave your contributions in the

pension fund and draw your pension when you finally reached the scheme’s pension

age. Your pension would be based on your salary

in cash terms when you left, so

still a huge gain to the fund when you eventually retired and you were given a

pension based on, for example, a 20 year old salary.

From 1986 anyone who left with at least five years in a fund could take the

value of their pension rights with them and transfer that value into another

pension scheme.

A

couple of years later, in April 1988, the five year period was cut to two years.

And at the same time the compulsion to join your company pension scheme was

ended. And those who were not committed to long term employment were no longer

in the scheme to be milked. Millions were missold personal pensions instead – at

a cost of £13 billion in compensation.

Then in April 2006 that 2-year period was cut to six months if you asked for it.

And

at the same time as your rights to get your pension out were enhanced, so was

the value of what you took out.

When you got nothing then it was still worth nothing when you retired.

Then in April 1978 the bit relating to SERPS was inflation proofed – like SERPS

with RPI but with a cap to make it not an open-ended commitment – only

Governments make those!

On

1 January 1985 all contributions made from that date had to be inflation proofed

– rising with prices measured by the RPI not earnings, and capped at 5% a year.

Then in 1991 inflation proofing of preserved rights was extended to the whole

pension whenever you paid in.

Then on A Day, April 2006, the tide turned with the first example of reducing

the rights in a final salary pension scheme – the cap on inflation proofing was

cut from 5% to 2.5%.

And

from April 2011 that cap will remain at 2.5% but the measure of inflation will

be changed to the Consumer Prices Index. And the maths of the CPI, the formula

used, means it is about 0.75% lower than the RPI given the same price data. So

another cut in rights.

Before these changes final salary pensions were particularly unfair to women. In

many companies women could not join the scheme.

The

Equal Pay Act of 1970 – Barbara Castle where are you now! – celebrated in the

film Made in Dagenham, did not

include pensions. It took years of campaigning and court cases to get the

European Union to declare that pensions were a form of deferred pay and so

extend the Equal Pay Act to mean equal access and contributions to pensions.

Even when women were allowed to join a pension scheme, if a woman married she

often had to leave her job – and lose her pension. She became an early leaver to

be robbed. Discrimination on grounds of sex was not illegal until 1975.

So

ending the practice of stealing from early leavers – many of them women – has

played a major part in making salary related schemes unaffordable.

So,

yes there was a golden age – for some. If you were with the right employer,

worked there for 40 years, and a man. But not otherwise.

Raids by politicians and increasing fairness to women and members who leave has

led to a crisis in private sector, funded, final salary schemes.

LIFE EXPECTANCY

I

haven’t mentioned life expectancy which just grows and grows and grows.

Let

me remind you briefly of the scale of it. Each October the Office for National

Statistics tells us how long we can expect to live. And it is always good news.

Last year using the tables I was due to die on 26 December 2029 at the age of

81. But when the tables were published for this year my date of death had

shifted by three months to 27 March 2030. A year on and I get three months more

life. And I have to cancel the funeral again!

And

for pension planning these life expectancies are an underestimate. Not just

because a lot of members are women who live longer, nearly three years more. But

because the ONS produces another set of life expectancy statistics which add

almost four years. A man who is 65 years old this year can actually expect to

live until he is 86 and four months and a 65 year old woman until she is nearly

89.

These higher figures are called ‘cohort life expectancy’ which takes some

account of the increase in life expectancy. It reflects the fact that not only

is life getting longer, every time actuaries look at what it might be in future,

it has grown again.

Actuaries, who had observed the rise in life expectancy for many years, always

used to say it can’t last. But in October 2005 the Government Actuary, Chris

Daykin, announced that he had stopped assuming that the length of life had some

ultimate biological limit. In other words, the age we live to really could go on

increasing forever. Or as he put it in actuary-speak

‘Previous projections have assumed that rates of mortality would gradually

diminish in the long term… However… the previous long-term assumptions have been

too pessimistic. Thus… the rates of improvement after 2029 are now assumed to

remain constant.’

‘now assumed to remain constant.’

It

is one of the most important pronouncements of actuaries ever since their

profession began in the 18th century when men walked round graveyards and noted

down birth and death dates and worked out the maths of life expectancy.

There is an easy answer of course – raise pension age. And as Hutton has

recommended in the public sector it will rise with state pension age to 66 by

2020 and then to 67 and 68 and probably more as time passes. Though that will

not necessarily apply to pensions in the private sector. Which may well then

have an advantage.

And

let me finally come to the main recommendation of Lord Hutton. Which tackles

another fairness which few people had recognised

STRUCTURE

In

his interim report Hutton noted that high-flyers can get double the pension

benefit from their pension contributions than those who are not high flyers.

This analysis was not original. It used a paper from 2007 by Charles Sutcliffe

of the ICMA centre at Reading University. He found that a high flyer whose pay

rose by 3.5% a year in real terms over a 40 year career would end up with pay of

just over double that of a low flying colleague who stayed in the same job for

40 years and gained no real rise in pay.

The

high flyer earns twice as much and therefore pays in twice as much to the

pension.

But

because the pension was related to final salary, the pension earned by that pay

was not 2.02 times higher but 3.83 times higher. And that means that for each

pound he pays in, High Flying Henry earned nearly twice the pension that Low

Flying Louise earns for each pound she puts in. (NB Hutton uses a female hi

flyer and a male lo flyer but that is not the reality of the sexist employment

world we live in).

Each £1000 of contributions Henry pays in buys him a pension of £178.24. Each

£1000 Louise pays in buys her just £94.18. That is a ratio of 1:1.89 – not quite

half as Hutton said but not far off. And you can devise scenarios which are even

worse. Hutton’s final report makes the difference a bit less using real public

sector data.

There is another inequality which Hutton ignored. High flyers are more likely

pay higher rate tax at some point in their career. So their pensions are more

heavily subsidised by the taxes paid by others – including poor Louise of

course. Every £1000 pound she pays in gets a Treasury contribution of £250.

Every £1000 Henry pays in gets a Treasury contribution of £667. That makes a big

difference and on my calculation increases the ratio of pension earned for each

£1 spent out of net income from 1.89

to 2.52.

And

beyond that, Henry, being richer and living in a nicer neighbourhood is probably

going to live longer – if not than Louise because nature does take its revenge

at this point on men for their lifelong selfishness towards women by giving them

shorter life expectancies – then certainly longer than low flying Louis – the

quiet man in the back office who keeps his low paid administrative job all his

life.

So

Henry will get a bigger pension; get more per pound contributed; pay less for it

due to the bigger Treasury taxpayer subsidy; and draw it for longer than low

paid colleagues. No wonder he’s called Hooray Henry. And as I am sure you know

Henry will not necessarily even be more capable than Louise. Late promotion and

the final salary pension promise have been used as a way to get rid of difficult

older staff or to free up posts for younger people.

Career average can end all those abuses. And that is why the civil service

pension scheme moved to it in 2008. At the moment the civil service scheme is

alone among public service pensions. But Chancellor George Osborne is likely to

accept Lord Hutton’s final recommendation to extend it to all.

And

I think you should embrace it. It is cheaper – but it is fairer and the way

Hutton has ensured that the pension that is already paid for is protected is

generous. The final salary pension earned up until the date of change – probably

2015 – will be preserved and related to final salary not at the point of change

– as you would expect in the private sector – but at normal pension age.

CONCLUSION

Let

me end as I began. Where are we on fair and adequate pensions?

I

said at the start that all the while that pensions just worked we never looked

inside the black box that converted contributions into an income for life at

pension age.

And

all three of those terms have now been attacked.

Contributions have risen and will rise again. Another 3% rise is planned from

2012 though how that will be shared out is not clear – except that the armed

forces will not face a rise. Now that is 3 percentage points for LGPS and TPS

will be around a 50% rise in their monthly contributions (3/5.5-6.5, 3/6.4). The

rise is likely to be tapered – so it will be higher for the high flying Henrys

and lower for the low flying Louises.

The

guaranteed pension has been cut – it will be less in future though still

defined.

And

the fixed pension age is no more. It will be raised under Hutton’s plans

automatically as state pension age and life expectancy rises.

So

all three of the attractions of these pensions have been challenged. That

undermines the psychological attraction of these pensions, and will lead some

people to leave their public service pension. One of my twitter followers, Sue,

who paid £150 a month into the LGPS told me on Money Box on Saturday

That is certainly a mistake. But understandable.

Because now that the three pillars of final salary schemes have been attacked –

and for the second time in a decade – who is to say that a future government

won’t come along when the last final salary scheme has disappeared from the

private sector and say ‘we can’t afford this. We will only support paying into

NEST at the minimum level of 3% employer and 5% employee and if you want more,

see an Independent Financial Adviser.’

Now

that would be the end of fair and affordable pensions.