This talk was given 26 October 2010

The text here may not be identical to the spoken text

THE

END OF FINAL SALARY PENSIONS

What is killing final salary pension schemes?

CONTRIBUTION HOLIDAYS

As

you may know the unions at the BBC are currently balloting on strike action over

planned cuts in the BBC pension scheme. As a freelance I am an interested

bystander in this. I am not in the BBC scheme and every penny in my own pension

I put in myself. Which is why I shall be working for many years yet!

But

one big complaint made by BBC colleagues was that the BBC had taken a

contribution holiday not paid into the scheme for 15 years. If it hadn’t done

that, the unions believe, it would not be in this mess now. It’s a common view.

Is it true?

Now

I don’t have to tell you that contribution holidays were not a voluntary

activity – although employers embraced them gladly they were actually imposed by

the Government of the day. Specifically by Nigel Lawson. When he was Chancellor

of the Exchequer he was very concerned that companies were using pension funds

as a means of salting money away tax free and then taking it back out later. So

he introduced a rule that if a pension scheme had funds which were worth more

than 105% of what the actuaries said it needed to meet its pension promises,

then that surplus could be taxed. So companies scrambled to reduce the surplus

in their scheme. The most popular means of doing that was to reduce the amount

they paid in. What we now call a contributions holiday. But there were other

techniques. You could enhance the benefits paid to scheme members or you could

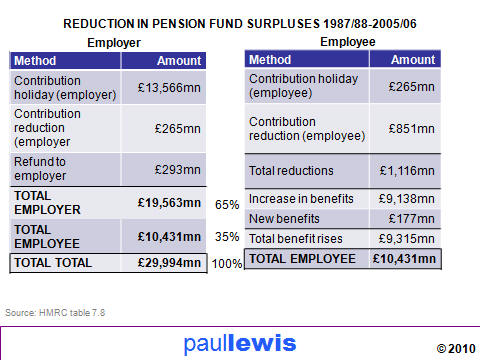

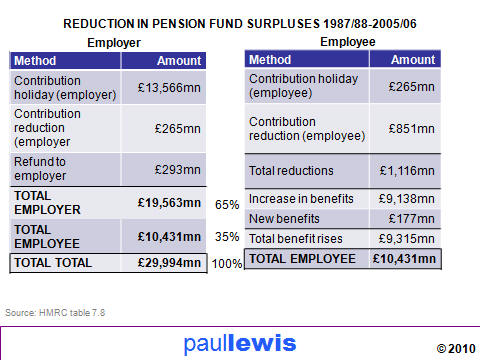

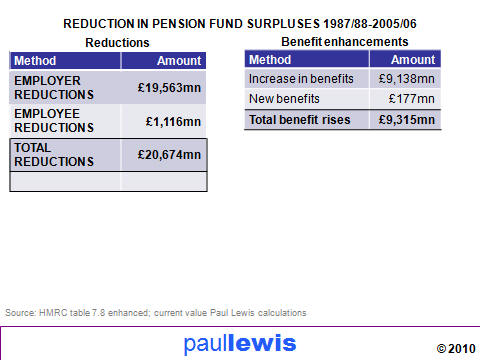

cut the contributions paid by those Here are the total amounts employers took

out – or stopped paying into – their pension funds from 1987 to 2006.

Over those 19 years employers took about £20 billion out of pension schemes,

employees benefited from cuts in their contributions worth about £1 billion and

were treated to enhanced benefits to the tune of around £9bn. So £21bn taken out

and £9bn of future commitments added. Though as you can see the benefits were

shared with two thirds in favour of employers, and almost all the contribution

cuts were by the employer.

But

these are historic cash figures. Between 1987 and 2000 the value of shares rose

as part of the golden quarter century. The FTSE 100 index – and I use that as a

proxy for investment growth to illustrate my point – grew by a compound rate of

8.84% from 1987 when the surpluses were first reduced to the year 2000 and 4.55%

a year from 1987 to now.

Most of these surpluses were taken out in the early years. And a rough

calculation indicates that if those holidays had never been taken and those

benefits had never been enhanced it would mean an extra £48 billion in pension

funds today.

And

don’t ignore those enhanced benefits. £9 billion worth. They mean more costs

further down the track. So not only was less going in but future commitments

were piling up. So contribution holidays and benefit enhancements – all

consequences of Lawson’s Law – have played a big part in the problems final

salary schemes face today.

I

will pass more quickly over the more familiar pensions raid by Gordon Brown. In

1997 the modernising Chancellor of the new Labour Government decided that the

way companies were taxed was so complex it reduced their incentives to invest.

So he changed the way dividends paid on shares were taxed. That had the effect

of taking away the tax refunds on dividends which pension funds enjoyed. Brown

insisted it was not the purpose of the change, and if companies saved money as a

result they could put it back into their pension funds if they had to. And later

he introduced the Pensions Regulator to make them do just that.

But

the total cost to pension funds and others of the change to the tax on dividends

was £5.4 billion in the first year. However, estimates by the Pension Policy

Institute calculated that the true cost to pension funds was much less – between

£2.5 and £3.5 billion a year, and that figure reduces over time. Today so many

other changes have happened that it is impossible to put the clock back and see

what if it had never happened. But it was certainly less than the potential

shortfall in those funds caused by Lawson’s Law. And between them? Maybe £60 -

£100bn off the current value of pension funds. I know that’s a bit vague – and

I’m not even an actuary.

One

final word on ‘contribution holidays’. It is easy to blame politicians. And fun.

And we know from those official figures that around £30 billion was withheld

from funds because of Lawson’s Law. But before that law began, some companies,

being told by actuaries that their pensions were over-funded, took contribution

holidays without being forced by Lawson’s Law. No-one counted them. So we do not

know how much it was or how much it added to current deficits.

FAIRNESS

Next candidate for what is killing final salary schemes is fairness.

The

mid 1970s on to the end of the 20th century is seen as the Golden Age

of Pensions. Good company schemes were affordable, reliable and secure. But it

was also the quarter century when the seeds of the destruction of final salary

schemes were sown. And one key part of that is often ignored – final salary

pension schemes stole money from people who left before they retired.

Remember that at the start of the Golden Age if there was a pension scheme you

had to join it. So everyone who worked for one of these top companies was

automatically enrolled in the pension scheme willy nilly, however long they

planned to work for the company and whatever their personal circumstances.

Until 1975 if you left the company you also left the pension scheme and you got

nothing. Or almost. The contributions you had made were refunded – minus tax

because you had made them out of tax-free income so the Revenue took that back.

But the fund kept the growth on those contributions. And it kept the

contributions paid in by your employer – which were always more than you had put

in. And it kept the growth on those too. So those who stayed in the scheme took

most of the contributions and all of the growth from those early leavers.

Over the next three decades that unfairness was removed piece by piece.

From April 1975 if you left the job you could leave your contributions in the

pension fund and draw your pension when you finally reached the scheme’s pension

age. Your pension would be based on your salary

in cash terms when you left, so

still a huge gain to the fund when you eventually retired and you were given a

pension based on, for example, a 20 year old salary.

From 1986 anyone who left with at least five years in a fund could take the

value of their pension rights with them and transfer that value into another

pension scheme.

A

couple of years later, in April 1988, the five year period was cut to two years.

And at the same time the compulsion to join your company pension scheme was

ended. And those who were not committed to long term employment were no longer

in the scheme to be milked.

Then in April 2006 that was cut to six months if you asked for it.

At

the same time as your rights to get your pension out were enhanced, so was the

value of what you took out.

When you got nothing then it was still worth nothing when you retired.

Then in April 1978 the bit relating to SERPS was inflation proofed – like SERPS

with RPI but with a cap to make it not an open-ended commitment – only

Governments make those!

On

1 January 1985 all contributions made from that date had to be inflation proofed

– rising with prices measured by the RPI not earnings, and capped at 5% a year.

Then in 1991 inflation proofing of preserved rights was extended to the whole

pension whenever you paid in.

Then on A Day, April 2006, the tide turned with the first example of reducing

the rights in a final salary pension scheme – the cap on inflation proofing was

cut from 5% to 2.5%.

And

from April 2011 that cap will remain at 2.5% but the chance of ever reaching it

will be reduced as the measure of inflation will be changed to the Consumer

Prices Index. And the maths of the CPI, the formula used, means it is about 0.5%

to 0.75% lower than the RPI given the same price data. So another cut in rights.

Your scheme may offer more than that – but my view is there will be a new law to

let you abrogate those contract terms – prediction not information!

Before these changes final salary pensions were particularly unfair to women. In

many companies women could not join the scheme.

The

Equal Pay Act of 1970 – Barbara Castle where are you now! – celebrated in the

wonderful film Made in Dagenham, did

not include pensions. It took years of campaigning and court cases to get the

European Union to declare that pensions were a form of deferred pay and so

extend the Equal Pay Act to mean equal access and contributions to pensions.

Discrimination on grounds of sex was not illegal until 1975. Even when women

were allowed to join a pension scheme, if a woman married she often had to leave

her job – and lose her pension. She became an early leaver to be robbed.

So

ending the practice of stealing from early leavers – many of them women – has

played a major part in making salary related schemes unaffordable.

So,

yes there was a golden age – for some. If you were with the right employer,

worked there for 40 years, and were a man. But not otherwise.

STRUCTURE

And

there is another unfair aspect of final salary schemes which was brought to

light by John Hutton – Lord Hutton of Furness as he now is –John Hutton, in his

interim report of the Independent Public Service Pension Commission, compared

final salary schemes with schemes where the pension is based on career average

earnings. And noted that high-flyers can get double the pension benefit from

their pension contributions than those who are not high flyers.

This analysis was not original. It used a paper from 2007 by Charles Sutcliffe

of the ICMA centre at Reading University. He found that a high flyer whose pay

rose by 3.5% a year in real terms over a 40 year career would end up with pay of

just over double that of a low flying colleague who stayed in the same job for

40 years and gained no real rise in pay.

But

because the pension was related to final salary, the pension earned by that pay

was not 2.02 times higher but 3.83 times higher. And that means that for each

pound he pays in, High Flying Henry earned nearly twice the pension that Low

Flying Louise earns for each pound she puts in.

Each £1000 of contributions Henry pays in buys him a pension of £178.24. Each

£1000 Louise pays in buys her just £94.18. That is a ratio of 1:1.89 – not quite

half as Hutton said but not far off. And you can devise scenarios which are even

worse.

Hutton gives the high flyer a woman’s name. And the low flyer a man’s. But that

isn’t the reality is it? We know that despite 40 years of equal pay laws women

earn less than men. We know that women have a lower chance of promotion than

men. And we know that women get lower pensions than men. And those facts are all

related. So I have stuck with the sexist reality not embarked on the political

spin of women out-performing men – some do of course; but men conspire to stop

them when they can.

And

of course from April 2011 when the 50% tax rate applies to taxable income above

£150,000 a year the subsidy will be even bigger. Someone on £250,000 salary who

puts the new maximum of £50,000 into a pension will find it is matched pound for

pound by a generous Treasury – yes from the taxes of those very people on

£15,000 a year who probably have no pension scheme and no personal pension

either. And just to be clear: you earn £250,000, put £50,000 into a pension

scheme out of your taxed income and George Osborne stumps up another £50,000 in

subsidy.

This slide is a bit out of date but it shows how the minority if higher rate

taxpayers get the bulk of the tax relief on pensions.

And

beyond that, Henry, being richer and living in a nicer neighbourhood is probably

going to live longer – if not than Louise because nature does take its revenge

at this point on men for their lifelong selfishness towards women – then

certainly longer than low flying Louis. The man in the back office who keeps his

low paid administrative job all his life.

So

Henry will get a bigger pension; get more per pound contributed; pay less for it

due to the bigger Treasury taxpayer subsidy; and draw it for longer than low

paid colleagues. No wonder he’s called Hooray Henry.

So

final salary schemes also work by stealing money from low flyers and giving it

to their bosses.

All

this assumes of course that Henry is promoted on merit. But you will know as

trustees that final salary pension schemes with surpluses have been used as a

way to get rid of difficult older staff, to free up the promotion ladder, or

just to give mega-rewards for friends of the directors.

Career average can end all those abuses. And that is why the civil service

pension scheme moved to it in 2008. At the moment the civil service scheme is

alone among public service pensions. But Lord Hutton seems set to recommend its

extension to all of them and Chancellor George Osborne looks ready to accept

Lord Hutton in full.

He

has already announced in the Spending Review that he would implement

Lord Hutton’s easy win of raising the contributions paid by millions of

people in public service pensions – police officers, firefighters, judges,

teachers, nurses, doctors, civil servants, local authority workers indeed all

public service pensions with the single exception of the armed forces. The rise

will be 3%, Or, more accurately, three percentage points. So for someone paying

6% now they will pay 9% from April 2012 – three percentage points is in fact a

50% rise in their contributions. It will save the government almost £2 billion a

year from 2014/15. And the Spending Review papers make clear that the cost of

exempting the armed forces – announced by George Osborne in his speech last week

to patriotic cheers – will be paid for by the rest of the pension schemes. So

the average rise will be slightly more than 3%.

LONGEVITY

Now

our next culprit – longevity.

It

is now a given that we are living longer – and longer – and longer. And that the

pension we and our employer have paid into will have to last for longer and

longer and longer. And it is inevitable that a finite pension will be worth less

and less and less when spread over more and more and more years. Final salary

pensions are a promise for life – however long that is. And as it stretches,

either we have to save more. Or we have to retire later. Or we have to change

the nature of the pension promise that is made. Or all three.

Let

me just remind you of the scale of it. Each October the Office for National

Statistics tells us how long we can expect to live. And it is always good news.

Last year using the tables I was due to die on 26 December 2029 at the age of

81. But when the tables were published for this year my date of death had

shifted by three months to 27 March 2030. A year on and I get three months more

life. These figures represent the age at which half those alive today will have

died and half will not. Some of that rise is due to the fact that I have

survived another year. But not much.

If

we take a man who was aged 65, a year ago he could expect 17 years and 135 days

of life. A man aged 65 this year can expect of life 17 years and 219 days of

life. Another 84 days = 12 weeks or nearly three months.

And

for pension planning these life expectancies are an underestimate. Not just

because a lot of members are women who live longer – not 17 years and 135 days

as a man might but 20 years and 87 days, nearly three years more. But because

the ONS produces another set of life expectancy statistics which add almost four

years to these life expectancies. They show that a man who is 65 years old this

year can actually expect to live until he is 86 and four months and a 65 year

old woman until she is nearly 89.

These higher figures are called ‘cohort life expectancy’ rather than ‘period

life expectancy’. Period life expectancy assumes that today’s life expectancy

will stay constant. Whereas in fact it won’t. Cohort life expectancy does take

some account of the increase in life expectancy. It

reflects the

fact that not only is life getting longer, every time actuaries look at what it

might be in future, it has grown again. And even though they build that error

into today’s prediction, next time they look it is longer still. Actuaries

who had observed the rise in life expectancy for many years always used to say

it can’t last. And tail it off in their future calculations. But in

October 2005 the

Government Actuary, Chris Daykin, announced that he had stopped assuming that

the length of life had some ultimate biological limit. In other words, the age

we live to really could go on increasing forever. Or as he put it in

actuary-speak ‘Previous projections have assumed that rates of mortality would

gradually diminish in the long term… However… the previous long-term assumptions

have been too pessimistic. Thus… the rates of improvement after 2029 are now

assumed to remain constant.’

‘now

assumed to remain constant.’

It is one of the

most important pronouncements of actuaries ever since their profession began in

the 18th century when men walked round graveyards and noted down birth and death

dates and working out a theory of life expectancy.

But back to my

life. When I first did this slide in 2004 the figures were these. I was

expecting to die in 2027. And in 1985 when I took out the first of my inadequate

pensions the arithmetic for how much was needed to pay me assumed I would die in

2024. So over that time I have gained six and a quarter years of life. And from

65 my life has grown by 58%. And so has the cost of providing me with a defined

benefit pension. Shame I haven’t got one!

There is an easy

answer of course – raise pension age, And with the state pension age rising to

66 by 2020 and then to 67 and 68 and probably more, occupational schemes will

have to raise their age too. Again legislation would be needed to make that

retrospective

INVESTMENT PERFORMANCE

Next is investment performance and the financial services industry

I

have missed out for time reasons the bit about the charges the financial

services industry levies. For an individual a quarter of their lifetime

contributions can go in charges. And any growth in the fund can easily be shared

50:50 with the fund manager. These charges are of course entirely unrelated to

the actual performance of the investment. They are levied whether the fund meets

its objectives or not.

The

industry says of course that the charges are worth it because you get better

performance. And the industry still believes in its maxim – if you want a bigger

reward you have to take a risk. But think about it – a risk doesn’t guarantee a

bigger reward. If it did it wouldn’t be a risk.

The

three largest public sector pension schemes in Canada lost 19% or C$72 billion

off their C$385 billion assets in 2008 because their active managers prefer to

put the money at risk in shares rather than keep it in safer bonds. Defending

this approach Jim Leech, the CEO of the Ontario Teachers’ Pension Plan which

lost C$20 billion, said ‘The fact of the matter is we have to take on risk to

meet our pension promise.’ Oh Jim! If taking a risk guaranteed those extra

returns you need so badly it wouldn't be a risk would it? The risk is you may

lose another C$20 billion. Perhaps he should have listened to Toronto teacher

Kelly Alles ‘A high return is great’ she told the magazine

Canadian Business in July 2008 ‘but

when it comes right down to it I'd rather have a guaranteed lower return’.

And

that is what is missing in pensions. Genuine options that allow money to be

invested in cash and other options that produces a guaranteed positive return

year after year rather than shares, property, commodities, balanced portfolios,

absolute return funds and the like – none of which do. My risk reward balance is

this. If you never take a risk you will be certain of a small reward.

TRUSTEES

And

finally in my list of things that threaten final salary pension schemes let me

add trustees. Many of you are amateurs. But you are up against the professionals

in the financial services industry. Who want you to take a risk so they can get

a reward. And you are in many cases up against the professionals from the

sponsoring company – the finance director, the head of personnel – sorry Human

Resources Director. Who want you to close down the scheme so they can shift the

risk to the members – and cut the contributions while they are doing it.

But

trustees have a sacred duty – to act in the interests of their members. And it

is never in the interest of members to lose a defined benefit scheme. But there

are difficult choices to make to find a change in a pension scheme to make it

sustainable, to help prevent it closing down.

And

I am sorry to say that nowadays, with no stealing from early leavers; with the

evidence about high flyers taking more out of the scheme than ordinary members;

with investment returns that are modest and charges that are anything but; the

fair and sustainable way to preserve defined benefit pensions is probably going

to be a career average scheme with, of course, a later retirement date.

Better to swallow those two bitter pills than throw your members on the mercy of

the financial services industry where they take huge charges from their

contributions, give them limited choice, poor advice, and no guarantees at all

except that after a lifetime of contributing their money purchase pension will

not be enough to live on.

Thank you.