This talk was given 22 June 2010

The text here may not be identical to the spoken text

CHARTERED INSTITUTE OF HOUSING

AGM

22 JUNE 2010 HARROGATE

So

cuts and housing. The very first piece I ever wrote for publication outside

university was about housing – specifically about homelessness. I suppose my

rather odd career can be dated from that moment. Although I am a financial

journalist my background is in the finances of the people who don’t have much

money. If you are rich you can afford an accountant or a financial adviser. If

you are on average income or below you can’t – you're stuck with me.

So

I am very glad to be here talking about housing. But before I talk about housing

I must talk a little about debt. Government debt is very big and can seem very

complicated. But it’s not. It’s just like personal debt, family debt, that we

have all had or, perhaps in our professional lives, all seen get out of hand.

There is nothing wrong with debt. Debt helps us manage our income, even it out

over time and buy the things we want but can’t afford. So some debt – debt of

the right sort – is fine if it is to cope with the ups and downs of life. For

example Christmas comes once a year so you might borrow a bit to afford that and

then pay it back. A holiday – perhaps this year an expensive one – ditto. Or a

new baby arrives. Or you move house. Those are examples of lumpiness in our

spending.

Income can also be lumpy. You may get a bonus or a bonus you expected may not

materialise. Or you may have a spell of unemployment. Or your partner has time

off sick and earns less. So income also goes up and down. And borrowing to tide

you over those hills and valleys is fine.

And

it is the same with the government. There is a business cycle – no-one quite

knows why – it’s like the long slow swell on the sea. As business does well the

wave of tax receipts rises above government spending and in the bad years tax

receipts fall and the government borrows to even out the waves.

Or

it should.

But

there is another sort of debt. On a personal level it is when you start paying

for your groceries on your credit card and don’t pay it off at the end of the

month. When you take a second holiday before you’ve paid for the first. When

your income is less every month and every year than your expenditure. And your

debt, instead of smoothing out the normal ups and downs of financial life, just

gets bigger and bigger and bigger.

And

if you are already spending more than you should, you’re a bit overstretched

year after year, then you get a sudden financial shock – unemployment,

relationship breakdown, major illness – or perhaps more relevant the bank

suddenly withdrawing your mortgage – that leaves a big problem to be dealt with.

And

that is what happened here.

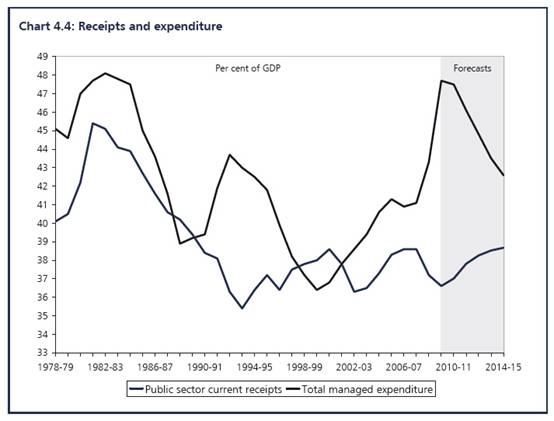

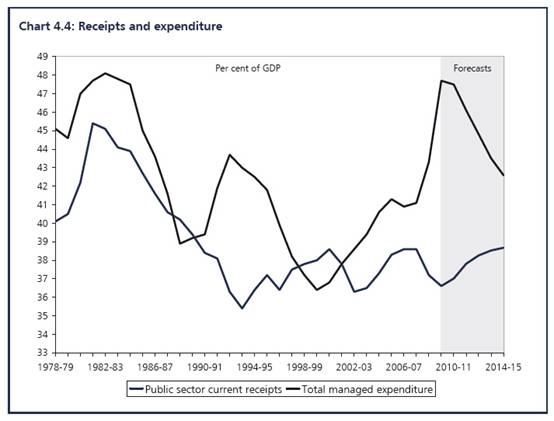

Source: Pre-Budget forecast, Office

for Budget Responsibility June 2010 p37

You

can see here the black line that is mainly at the top is our spending, the dark

blue line mainly at the bottom is government income. The grey box represents

predictions. And you can see that it has been more than expenditure fairly

constantly for a very long time but recently it has really taken off.

And

that sudden increase in our deficit is the damage done by the financial crisis

of 2008. Although the government had been spending too much it was not on a

crisis scale. But it was on a scale which meant that the crisis and the costs of

it could not be accommodated.

The

annual overspend is called our deficit. And there are two parts to it. There is

the cyclical deficit – that’s just the smoothing out of our finances year by

year. And there is the structural deficit – that is the underlying overspend.

The amount that represents living beyond our means. Now some structural deficit

is normal. But we have suddenly got a much large deficit because of the

financial shock which the economy had to deal with.

The

latest figures show that the deficit will be about £155 billion this year

The

debt is the total of all those deficits. And again that is put at £936 billion

this year.

And

here it is worked out as an amount per adult – each one of us in the country.

And

even on present plans – before today’s announcements – that debt is going to

grow. Because however you tackle the overspend you won’t get rid of it in one

year even in five years. So it will grow.

It

is this structural deficit – the underlying overspend or at least the part of it

caused by the recent crisis – that is being targeted by the coalition

government. The Institute for Fiscal Studies says that is about £74 billion

rather than £69 billion that was estimated at the March Budget. So although last

Monday’s figures from the new Office for Budget responsibility found some

improvements to our finances, it showed that this problem deficit was rather

bigger than we thought.

And

the coalition government seems set to announce in an hour or so that at least

this emergency structural deficit will be eliminated in the next five years. And

it may move towards having a much smaller or no structural deficit at all. That

could mean cuts of between £75 billion and £85 billion over five years. That is

a huge target. It means cutting up to one pound in every eight of everything the

government spends.

Now

some of you may have seen my presentation at the Wales CIH meeting two months

ago. If you want to read it, it is on my website. The essence of what I said

then about reducing the deficit is that out of the £701 billion spending a lot

of it is sacred. The most sacred of all, I’m sorry to say, is the £42.1 billion

in debt interest this year which will rise to £67.2 billion by 2014/15. Now that

figure seemed to come as a surprise to David Cameron when the OBR published its

report. It shouldn’t have done. It was available and indeed it was published by

me at the Welsh CIH meeting.

Now

there is little we can do about the debt interest. It rises for two reasons.

First our debt will continue to get bigger – remember that cutting the deficit

means that the overspend will be less each year but it will still be an

overspend. So the total debt will carry on growing. It will just grow more

slowly. The second reason is that as the people who lend us the money get more

worried about our growing debt they charge us more. Just as an individual with a

poor credit rating pays a higher rate for a loan. And one thing we cannot not

pay is the debt interest.

Now

this year the £42 billion is as much as we spend on defence. A third of what we

spend on the NHS. Just on servicing our national debt.

And

it’s not just debt interest that is protected. Spending on the NHS is not being

cut either. Indeed the coalition has promised it ‘will rise in real terms in

each year of the parliament’. So it will rise by more than inflation. Now that

is not to say it will rise enough – it has to rise 1.6% a year just to stand

still. So it may feel like cuts but it won’t be. And overseas aid will also be

protected rising to its target level by 2013 – now that is a big rise but it’s a

small amount of money.

But

everything else is in line for cuts. And that includes the previously protected

amounts on welfare benefits. We have already seen speculation that housing

benefit – help with rent – could be cut. Child benefit currently paid for every

child in the country – could be means-tested or taxed. Even winter fuel payments

– which the coalition has said it would ‘preserve’ – may not be fully protected.

And we know there has been discussion of a complete benefits freeze – for a year

or maybe more. That would almost certainly exclude the

basic state pension. But everything

else including pension credit, SERPS, bereavement benefits, disability benefits,

could be frozen. And with the RPI at 5.1% and projected to be still as high as

3.3% by September when benefit rates are fixed – that would represent a real cut

in the weekly money paid to millions of people, most of whom by definition – by

any definition – are poor.

Apart from benefits it includes absolutely everything else – including public

sector pay and pensions. Including defence. Including the police. Including

schools. Including universities. And of course including housing and the

spending of local councils.

Calculations vary but suggest that, depending what happens with welfare

payments, other spending that is not protected would have to be cut by about 25%

by the end of the parliament 2014/15.

And

on the other side there will be tax rises. Again, we are in the realms of

speculation. But to raise serious money you have to increase the taxes that are

paid by most of us – Value Added Tax which could go up or be extended its scope

to the things that are currently zero rated or exempt such as food or children’s

clothes. Not income tax because that has not been raised since it was put up to

35% in 1975. Since then it has only come down, despite being the fairest tax.

But National Insurance paid by everyone in work is also a likely candidate. That

is a soft way to raise a tax on income.

So

taxes will rise and that will harm low income people as much as or more than

those on higher incomes.

At

the end of the Budget we will know more – but not everything. The cuts in

departmental budgets almost certainly won’t be announced until the Autumn. We

will know the overall figure today but where the axe will fall won’t be decided

just yet.

But

we do know that the people making the decisions are politicians. And they will

tend to push those decisions onto others if they can. And particularly they will

push them down to local politicians. So expect big cuts in local government

budgets. Already we have been told that council tax will be frozen in England at

least – though how that will work is not clear. That will take money away from

local councils and leave them to work out how to do it.

And

all of that will mean big cuts in housing programmes.

The

National Housing Federation estimates that there will be cuts in housing budgets

up to 32%. That would reduce the number of affordable homes being built over the

next nine years from 426,000 to 285,000. There are 4.5 million people waiting

for an affordable home, 2.6 million people estimated to be in overcrowded

conditions. And 1.8 million on local authority housing waiting lists.

Let

me look at the broader housing market – not just what we rather glibly call

affordable homes. In London ‘affordable’ is a technical term which does not mean

anyone on an ordinary income can afford it.

So

house prices. One of the abiding interests of Money Box listeners.

Here is what has happened to house prices over nearly the last fifty years since

1952. Figures from Nationwide. There are others but they all show much the same.

And

we can see that overall the trend for house prices is up. There have been two

occasions when they fell. They peaked in Q3 1989 then they fell for 14 quarters.

And it took another 9 quarters to rise back to where they were. Then they peaked

in Q3 2007 and fall for 7 quarters and then rose so far for the next three.

They’re still rising. But is this a bubble?

In

one sense clearly not prices did not collapse they fell sharply but they soon

began to rise again. And we can see how house prices have risen compared to

retail prices. This series goes back to 1952 as well. And you can see that since

the 1970s at least houses have been a great hedge against inflation. Rising in

real terms very strongly.

But

that doesn’t tell us anything about whether they will fall again. More important

we are told is how house prices compare to earnings. After all it is earnings we

use to justify the loan we take out to buy them.

So

here in green is earnings. They start from 1963. And you can see that they

pretty much follow a smoothed out line like house prices and when prices got out

of kilter with them in the late 1980s they soon fell back to fit in with

earnings.

But

now it is very different. They have taken away quite separately from earnings

and far from plunging back down to earnings they are still way above them. If

they were back to where they were in 1963 the average home would cost around

£100,000 not more than £160,000. So are they really that overpriced?

Halifax says that the average home costs 4.63 times average full time male

earnings. And many people say that is unsustainable that prices must fall so

that people can afford them.

But

there is no rule that says the price of houses has to be low enough that

everyone can afford them. Suppose there was a weapon which could destroy a

million homes overnight without harming any people. But wages stayed the same.

Would house prices stay the same? No. They would go up. Because there would be

less homes. Because although there is no rule that says average earners have to

be able to afford a home there is a rule that says if the demand for a product

exceeds the supply then the price will rise. It is the e=mc2 of

economics – supply and demand.

And

every figure we have shows that there are too few homes for the people who need

them. Not just homes to buy of course but all homes in all tenures.

Here is a projection by the admittedly upmarket estate agent Savills. It shows

how household formation is growing much faster than the number of homes that are

being built. It predicts that by 2015 there will be a shortage of more than a

million homes. And the steepness of this graph shows that the problem will get

worse and that will drive up prices.

Last year we built 122,000 new homes – the lowest number since the 1920s.

But

surely, people say, if these new households can’t afford a home then demand

falls and prices will follow. In the past they have afforded it because banks

and lenders have given 100% mortgages at huge multiples of annual pay. That is

no longer happening. So if people can’t borrow what they need prices will fall –

they may want a home but they do not created demand because they cannot enter

the market. That might be true if Britain was an island. Now I know it is an

island but it is one which is linked to the rest of the world by countless

bridges.

And

figures from published again by Savills in June showed that 55% of the homes it

sold for more than £750,000 were sold to foreign buyers. That compares with only

45% of those homes sold to foreign buyers at the price peak. It is partly

fuelled by the weak pound which makes the prices seem more attractive to those

with foreign currency to spend. Savills estimates that property prices are about

10% below their peak. But if you have US dollars or euro they are 30 or 33 per

cent below their peak. So they seem very attractive.

Now

this affects particularly London and only as I said high end properties. But the

price of those tends to pull the whole market up. And remember £750,000 will

only get you a modest three bedroom home in much of London and not even that in

some parts.

And

even if demand is limited by the lack of finance or affordability, there is

another factor that keeps prices high.

Prices are currently 10% below their peak. People with homes who have seen them

at one price two years ago are very reluctant to sell for what they see as too

low a price. So homes are kept off the market. So even if demand is controlled

by the banks lending policies supply is also controlled while prices are below

their peak.

So

this gap on the graph between wages and average prices of a home does not mean

that prices are going to crash. We are short of homes, the finance or the

foreign buyers are there for enough of those who want to buy to keep prices

high.

HOUSING TENURE

One

factor that keeps up demand is the way housing is organised in the UK. For most

people there is only one way to have a secure home – buy it. If you pay the

mortgage eventually you will own it and then you can stay there. If you retire

and your income falls you still have a home. Yes you have to pay for repairs and

insurance but you will not be evicted.

That security does not exist in the private rented sector except for a dew very

elderly people who have lived in their rented flat for decades. But when I was

young – to return to the start of my talk – tenants did have security of tenure.

And the state did control rents. So with reasonable rents and a secure home the

urge to buy was far less.

Today a new secure shorthold tenant has security for six months. Even if they

pay their rent on time the landlord can evict them for no reason with two

month’s notice.

One

way to reduce the demand on housing and ironically to make it more affordable

would be to restore security of tenure and rent control. And it would save

public money. At the moment with no rent controls landlords can often get their

high rents paid for wholly or partially by the state through housing benefit. We

may well see cuts in HB later today. But that will only make the position of

private tenants worse if it is not matched by rent controls and security of

tenure.

Of

course in the public sector tenants do have security. But for how much longer

will that apply to new tenants? Housing Minister Grant Schapps told Parliament

on 10 June

Grant Shapps:

As I have said, security of tenure is incredibly important, particularly for

people in social housing, and we are keen to protect that. There are 1.8 million

families languishing on that social housing waiting list, and it is right and

proper that we look at the way in which we can reduce that list. It may include

looking at tenure for the future. (col 451)

As

I understand it that does not mean taking security away from existing tenants

but only giving those on the waiting list a home on a shorthold tenancy rather

that with security. I am not quite clear how that helps provide more homes for

them – at least on a permanent basis – but that is certainly on the agenda. And

it does seem a less than convincing statement of future government commitment to

security of tenure for social housing tenants.

To

sum up.

Cuts are coming. They will be worse than anything we have seen before. And they

will inevitably hurt most those who can bear them least.

The

only answer to the unaffordability of housing is to build more, to raise supply.

And to reduce demand by making tenancy more attractive. There is no indication

either of those things is going to happen. So house prices will keep ownership

out of the reach of many. And reforms to rented accommodation will not happen.

Housing is not a priority of any government. So overcrowding, under investment

and waiting lists will get worse. And local authorities will be blamed.

And

if you think that’s depressing wait till you hear George Osborne in an hour or

so.

Thank you.