This talk was given 19 March 2010

The text here may not be identical to the spoken text

Pfeg in partnership NW Conference

19 March 2010

Hello. I’m Paul Lewis a freelance financial journalist, although best known I

guess for my work presenting Money Box on Radio 4. But I also write the money

pages in Saga Magazine and write for its website. And if you have trouble

sleeping you can read everything I have written since 1996 on my website or on

one of theirs.

But

I am not here representing Saga, or Money Box or, god forbid, the BBC.

Over the last few months I’ve been thinking about personal finance education a

lot. Part of me thinks that it’s a waste of time. That’s not to say it’s a bad

thing. I have spent most of my professional journalistic life helping people to

understand the obscure and arcane rules that govern personal finance. Including

such delights as married women’s national insurance contributions, benefit

crystallisation events, and the impact of the order of payments on credit card

debt.

But

as I do so a part of me always thinks – why do I have to do this? Why are the

rules so ridiculously complicated that people – ordinary educated people – need

hand-holding through what should be fairly simple. It’s only arithmetic after

all. But then I heard this fascinating programme by my colleagues on Woman’s

Hour and broadcast a month ago. The programme began with this question

What is 1.12 x 2.2

It

was we were told a calculation an 11 year old should be able to answer. But a

fifth of adults have numeracy skills below those of that 11 year old. And adult

women are more likely to have poor numeracy than adult men – a third of women

say they struggle with maths. And a third of parents say they avoid helping

their children with their maths homework because they feel incapable.

The

programme then played this selection of women asked are you good at maths?

And

what is 1.12 x 2.2? 2.464

The

reason the banks make money is that they are better at arithmetic than the rest

of us. And yes even now the retail bits of the banks are highly profitable –

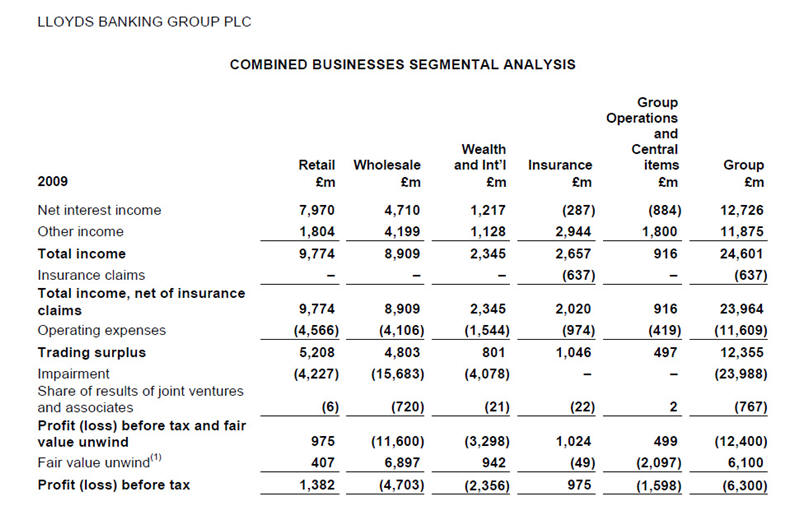

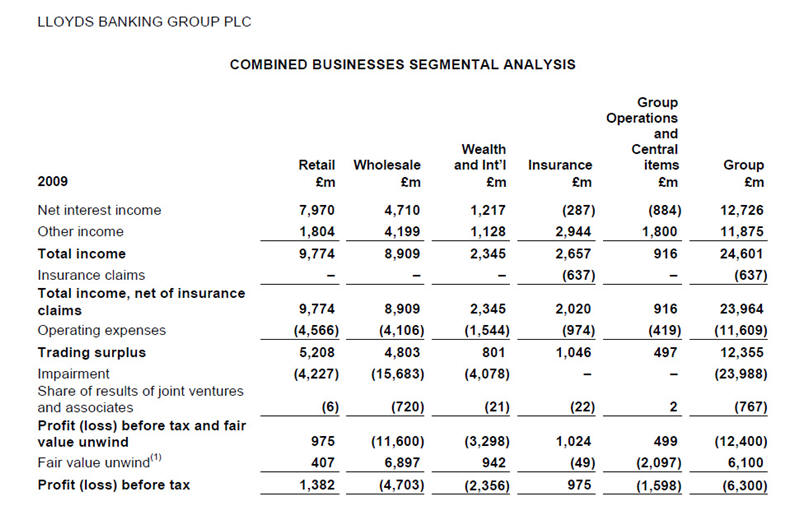

Lloyds Banking Group for example made huge losses on much of its business. Total

losses of £6.3 billion.

But

as these figures show it made profits on two retail activities – banking

£1.382bn and insurance £975mn. A total of nearly £2.4 billion. And the same is

generally true of the other banks. Some lost money some made it last year. But

they all made money on their retail activities.

Because they are better at arithmetic than the rest of us. No amount of

financial capability training is going to change that. It is like trying to give

everyone tennis capability so they can stop losing money when they play Roger

Federer. It is not going to work.

So

personal finance education has to do improve arithmetic. Without that you can’t

teach about money. Because ultimately money is arithmetic.

The

other reason people need financial capability is because the products they are

sold are complex, the descriptions of them are misleading, though usually true,

and some of them are dangerous.

It

is part of a process which I call complexification. Making financial services so

complex that the human brain cannot make rational choices, ends up making bad

ones, but usually doesn’t even understand what it has done wrong. And if it does

work it out and complain it is referred to paragraph 94(a)(i) blobby point five

which, somehow, they failed to read and understand before they bought the

product.

So

financial capability is a problem for the financial services industry not for

the consumer. If we accept, even for a moment, that it is the confused who are

to blame rather than those who are confusing them, we turn mis-selling which is

rife and an embarrassment for the industry, into mis-buying which lets them off

the hook if they put a few pounds into a financial capability programme.

And

it is a only few pounds out of the total cost of policing the UK financial

services industry and compensating customers when things go wrong will, in

2010/11, top £1 billion for the first time. That is more than £20 for every

adult in the country. And we all pay it through the price of insurance, loans,

mortgages, investments, and banking services – including the low rates on

savings accounts.

Almost half that billion pounds is needed to pay for the expanding Financial

Services Authority. It is taking on 460 extra staff – in addition to the 280

extra recruited this year. The FSA has already announced it will have to pay its

staff more money to recruit and keep the quality people it needs. Since it began

to be fully operational in 2000 the cost of the FSA has rocketed from under £200

million to a forecast of almost £458 million in the coming year. One reason is

that it now regulates more sectors – insurance and mortgages have been added –

and it is now expanding further to make sure its supervision of banks is rather

better than it was before the 2008 crisis. So that’s the FSA.

Slightly more – £505 million – will pay for the Financial Services Compensation

Scheme. It coughs up when people lose money due to regulated firms going bust

and owing people money. About three quarters of the cost is interest on the £20

billion which the Treasury lent the scheme to ensure savers got all their money

back when five banks and one building society went bust in the crash of 2008.

No-one knows when or if the capital will ever be repaid but the interest has to

be repaid annually. That cost is about £375mn and the rest, say £130 million, is

the estimated cost of direct compensation for other failed firms.

Add

on nearly £114 million to run the Financial Ombudsman Service and almost £33

million for financial capability – which will soon be the responsibility of a

new consumer financial education body – and the grand total comes to £1.1

billion. All of which will be added on to the price of the financial products we

buy in 2010/11.

So

there is £33 million for financial capability out of more than £1 billion to

police the financial services industry and compensate customers for its

mistakes. In other words what is being spent on helping us to understand the

complex products which the industry sells is just 3% of the total cost of

putting things right.

And

the danger is by putting a small amount into financial capability the industry

will buy itself out of the whole mess of mis-selling which has dogged it since

it really began in its present form with the great liberalisation of pensions in

1988.

When the first personal pensions went on sale on 1 July 1988 the pensions

industry thought Christmas had come very early. At last they could sell this

miracle of personal pension pots to not just a few tens of thousands of the

savvy middle classes. But to the mass millions. What could go wrong?

As

we now know the industry contrived the biggest financial mis-selling scandal we

have seen so far.

It

sent out teams of poorly trained, commission driven sales staff to descend on a

hapless population who believed the adverts and newspaper stories which said

that for a few pounds a month everyone could buy not just financial independence

but protection from the danger of future political cuts in state pension. The

public was gladly mis-sold £11.5 billion worth of personal pensions. Eventually

the industry had to spend £2 billion finding the nearly two million people

affected and repaying them the £11.5 billion they should never have put into

their own pension in the first place.

And

now fast forward to the present. Pass over half a dozen mis-selling scandals

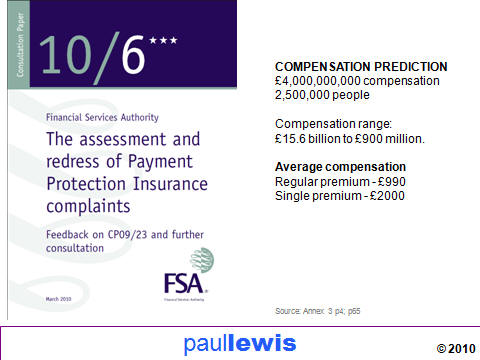

since the 1990s and skip to this month. The FSA told us last week that two and

half million people who have bought loans and credit cards have been mis-sold £4

billion of insurance to protect their payments so-called Payment Protection

Insurance. Here is the paper. Now I give those figures £4bn (A3:4 para 12 blob

3) and 2.5 million people. They are in there. But so is a whole range of other

figures – ranging from £15.6 billion redress to as little as £900 million. But

that is a fair estimate of what the total could be.

And

these that 2.5 million people could be owed quite substantial sums. The average

for regular premium PPI is £990 and the average for single premium PPI – where

the insurance was paid upfront and more money lent at high interest to pay the

premium a product now effectively banned – is around £2000.

Let

me remind you why Payment Protection Insurance was such a bad idea. Because,

like most financial products, it sounds

a good idea. Until you read the small print. Many people (including those who do

not work or are retired) are excluded from claiming but were still sold the

policies. Many others who appear eligible are refused pay outs because they had

existing medical conditions (often irrelevant ones) or lost their job in the

wrong way. And even those who make successful claims – and about one in five

claims were turned down – find that the insurance only covers the interest on

the loan for a limited period. On top of that the cost of the insurance was

sometimes as much as ten times the market rate. CAB estimated that customers

were overcharged up to £3 billion a year. As a result this insurance can double

the cost of the loan. And of course its sales were driven not by the fact that

it was a good idea but by the high commission and incentives paid.

So

who was selling these duff policies? Since 2006 the FSA has taken enforcement

action against 23 firms and levied fines totalling more than £12.6 million.

Here is the table of fines – and you can see that the top fines are to banks and credit card providers – and, as you move down the table, furniture shops and used car salesmen.

|

Date |

Firm |

Fine |

|

7 Oct 2008 |

Alliance & Leicester |

£7,000,000 |

|

16 Jan 2008 |

HFC Bank |

£1,085,000 |

|

30 Jul 2008 |

Liverpool Victoria |

£840,000 |

|

28 Oct 2009 |

Swinton Group |

£770,000 |

|

10 Dec 2008 |

Egg banking |

£721,000 |

|

31 Jan 2007 |

GE Capital Bank |

£610,000 |

|

26 Oct 2006 |

loans.co.uk |

£455,000 |

|

20 Dec 2006 |

Redcats |

£270,000 |

|

12 May 2008 |

Land of Leather |

£210,000 |

|

15 Feb 2007 |

Capital One Bank |

£175,000 |

|

6 Sep 2007 |

Hadenglen home finance |

£133,000 |

|

21 Aug 2008 |

Parks of Hamilton |

£61,600 |

|

5 Sep 2006 |

Regency Mortgage Corporation |

£56,000 |

|

8 Dec 2006 |

Home and County Mortgages |

£52,500 |

|

21 Aug 2008 |

GK Group |

£51,100 |

|

6 Sep 2007 |

Richard Hayes CX Hadenglen |

£49,000 |

|

21 Aug 2008 |

Ringways Garages |

£35,000 |

|

21 Aug 2008 |

George White Motors |

£28,000 |

|

21 Nov 2006 |

Capital Mortgage Connections |

£17,500 |

|

12 May 2008 |

Mr Briant re Land of Leather |

£14,000 |

|

2006-2008 |

TOTAL |

£12,633,700 |

These products were almost exclusively mis-sold by banks, insurers and their

agents. Which is where the true problem of commission driven sales is to be

found. Usually commission driven selling is a charge laid at the door of

Independent Financial Advisers. But not today.

Because I want to come back to financial advice.

When people need financial advice you might think they could go to a financial

advisor. And when we hear that term we think first of independent financial

advisors or IFAs. But sadly financial advisors are generally very bad at

financial advice in the natural meaning of those words.

The

first thing to say is that ‘financial advisor’ is not a regulated term. I am a

financial advisor and could call myself that and charge money for it. Many of

you are financial advisors. Indeed anyone from the economist who you hear on the

Today programme to the loud mouth in the pub who would like to tell the

Chancellor how to cut spending could all call themselves financial advisers.

What is regulated is the term ‘independent’. Independent financial advice is a

regulated term and to call yourself that you have to jump through all sorts of

hoops including qualifications, how you behave and how you’re paid. And most

important of all you can’t do anything without printing at least a ream of paper

– on both sides – and sending it to your client.

Although financial adviser isn’t regulated, giving advice on certain subjects is

also subject to regulation. Advice on mortgages, insurance, investments, and

savings are all subject to strict rules. So as an unregistered financial adviser

I have to be careful what I advise on. But most financial advice that people

need is not subject to rules and is generally not given by independent financial

advisers. If I asked you to name twelve things people

want financial advice on you might come

up with

1.

Debt

2.

Mortgages

3.

Credit cards

4.

Social security benefits

5.

Insurance

6.

Income Tax

7.

Pensions

8.

Bank accounts

9.

Tax credits

10.

Investment

11.

Budgeting

12.

Savings accounts

Out

of those twelve, how many can High Street IFAs give detailed advice on?

Pensions – yes

Investment – yes

Savings accounts – Maybe.

Mortgages – other retail intermediaries

Insurance – other retail intermediaries

Debt? – no. Some IFAs will not even say pay off debt before you save or invest.

Credit cards? – no.

Social security benefits? – pass. That’s the DSS or something isn’t it?

Holiday money – no.

Income tax? – They may know that ISAs are tax-free and have a wheeze for

avoiding IHT but they can’t check PAYE.

Bank accounts? – Nope.

Budgeting – I find it hard to make ends meet. Not me.

So

if financial advisers can’t give advice on at least half and probably three

quarters of the financial problems people have why are they called financial

advisers? And to use the FSA’s own terminology is calling them financial

advisers ‘clear, fair and not misleading’? I don’t think so. It misleads

customers to expect more of them than most can deliver.

Financial advisers concentrate on things that pay – or used to pay – commission.

Pensions being one of their big items. And investments being the other.

And

all young adults who come into contact with the financial world will come across

IFAs and other advisers and here are two things they should be taught.

First saving and investing. They are not the same thing. But are frequently

confused in financial advice. And not just by advisers. Ask Her Majesty’s

Treasury the difference and it will call a shares based ISA a ‘savings account’.

But there is one very simple difference between saving and investing.

If

you save, your money remains yours.

If

you invest, your money belongs to someone else.

It

is that simple.

Suppose you have £500 to spare.

You

go to the bank and put it into a savings account. The £500 remains yours. You

have lent it to the bank. A year later, you need the money back. You go along to

the bank and take it out and, hey, the bank has added £10. It takes off £2 tax

which leaves you with a profit of £8. And you have done no work! Magic!

Alternatively you invest it.

You

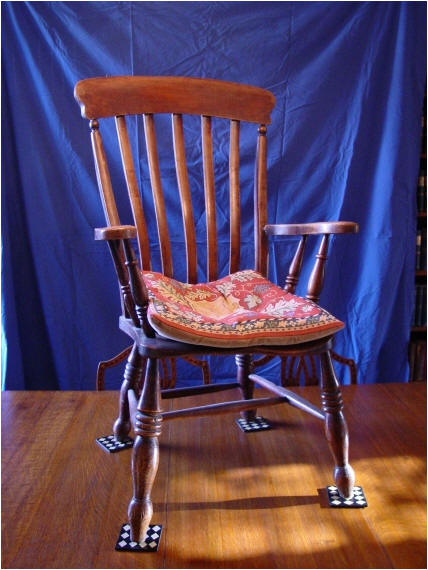

go to Mr Oldenshaw’s antique shop. You see a really nice antique chair for £550.

You bargain with Mr Oldenshaw and hand over £500 in tenners. He gives you the

chair. You take it home and you sit on it - carefully. A year later, you need

the money back. You can’t take the chair to the bank and cash it in. You have to

sell it. So you take it back to Mr Oldenshaw. But now Mr O, who really loved

that chair and told you how rare a chair of that age was, especially in that

condition, now says the market for brown chairs has really dried up recently and

the most he can give you is £200. And that is cutting his own throat. You

invested £500 you get £200. Loss £300.

That’s the difference between investing and saving. Many people think that,

because many things called ‘investments’ involve money rather than furniture,

the money they use to buy them is still somehow ‘theirs’. It is not. Just like

when you buy a chair. The money is someone else’s. The investment is yours. To

get your money back someone has to buy it from you, at the right price, when you

want to sell it.

How

many financial advisers make that clear distinction – do you want to save or

invest? And if you invest you may not get your money back. It is that simple.

And

that brings us of course to risk. Risk simply means that there can be a happy

ending and a sad ending. And often the difference between them is out of your

hands.

I

still hear though financial advisers say “Well normally risk provides reward, so

over the longer period of time you would expect the stock market, which

obviously is the highest risk, to provide you the highest returns.” That’s a

direct quote from a well-known IFA on Radio 4 in February 2005.

‘Risk provides reward’ No it doesn’t. Risk means you can lose money.

And

assessing what the industry calls customers’ ‘attitude to risk’ is not done

well. Because most people haven’t got a clue. What’s your attitude to risk?

‘Well, I do the Lottery, I like a flutter. I take a chance now and then.’

‘I’ll put you down at medium but erring on the adventurous side then?’

‘Yeah OK’.

Here is how I would assess attitude to risk. Ask them this

‘You’ve got £1000. You follow my advice and invest in this product. In a year’s

time it’s worth £600. How will you feel?’ What do they say?

·

Terrible – I worked hard for that money and I did not want it lost to someone

else.

·

Quite happy – I knew I could lose it but I also knew there was a chance I could

make more than I could in a savings account. It was a bet. I lost. Some you win,

some you lose.

·

A

bit upset – I was told it was a risk but I did not really expect to lose money.

You don’t do you?

Risk means you can lose your money. But if advisers don’t explain that clearly,

and the investment doesn’t turn out well, they get upset. And complain.

We’ve seen the sad ending with the chair. But there is a happy alternative. You

take it to Chairstyle, a specialist dealer. Miss Carver takes one look at it and

her eyes light up. She has just the customer who needs your chair to make a nice

mixed set of six. After some bargaining you settle on £600. She writes you a

cheque – and it doesn’t bounce. Profit £100. What a great investment. I took a

bit of a risk on that chair – but I got my reward 20pc growth in a year.

So

risk goes both ways. Put it in the bank and there’s no risk – you know you will

make a small amount of money. Buy a chair and there is a chance you will make a

lot more money than you would in the bank. But there is also the chance you will

lose money. That is what risk means. You gamble the chance of making more money

against the chance of losing some – or exceptionally all – of the money you

invested.

But

advisers have an answer for that analysis too, They say there

is a risk in putting the money in

the bank. In ten years’ time it may not have kept up with inflation. You’ll have

less than when you started.’ And today with even the best interest rates around

2.5% taxable so worth 2% to a basic rate taxpayer. Yet inflation is 3.5% in

January (3.7% on RPI) and rising. So money in the bank won’t even keep up with

inflation never mind provide you with an income.

That’s what the arithmetic shows. But it is not an argument for investing rather

than saving.

I

was interviewing someone who runs a major financial services company about the

risk of putting money in shares. And he said – I paraphrase – ‘the real risk is

putting it in a cash savings account. And ten years later it is worth less than

you put in because of inflation. That’s the really risky option.’

Of

course there is the possibility that inflation will have exceeded returns on

deposit accounts. But over that period of time you have to discount the same

amount for inflation whatever you do with your money. So there is no particular

‘risk’ that affects a deposit account. It is just inflation. And if you put it

on the stock market or in gilts or bonds or National Savings it may not keep up

with inflation either. It is just sloppy thinking used to confuse people. To try

to make them feel that deposit accounts carry some sort of ‘risk’ which is the

same as the ‘risk’ which attaches to share based investments. It is not true. It

is misleading

And

I am worried about another misleading statement that is being said about

pensions.

Pensions are a good thing. We should all be putting money into a pension because

the state won’t provide for us. Put in whatever you can afford now and put in

more when you can afford it.

Let

me tell you a story of two brothers.

James, who was born in January 1935, started paying into his pension when he was

45 in 1980. Very late but that’s not unknown. He put quite a lot in, £100 a

month. And he opted for a sage stock market investment in what is called a

balanced managed fund. He liked the words balanced and managed. James picked his

timing well. He benefited from the huge year on year stock market growth of the

last quarter of the last century. Around 12% a year. So by the time he reached

65 in January 2000 his £100 a month would have grown to £103,914. At that time

James got an annuity – a pension for life – of £866 for each £10,000 in his

fund. So his pension was £8,998 a year.

James’s brother Jonathan was born ten years later in January 1945. And like his

brother he put £100 a month into his pension from the age of 45. And he too

chose a balanced, managed fund. He benefited from ten years reasonable growth

from 1990 but then he hit the millennium and his money languished in the

stagnation of the last decade. Despite recent stock market rises share prices

are still roughly where they were 12 years ago in February 1998. So his fund

wasn’t so much balanced and managed as stagnant. When he reached 65 in January

2010 his £100 a month ended up as a fund of just £40,749 – 60% less than his

brother’s. And annuity rates – the amount of pension you get for your money –

were also down.

By

the time Jonathan came to hang up his boots each £10,000 of fund bought a

pension of just £624 a year, 28% less than his brother got.

With his fund 60% less than his brothers and his annuity 28% less he got a much

smaller pension of just £2,542 a year – 72% less than his brother’s.

This ten year graph shows how it has changed. That blue line is the value of the

pension fund from £100 a month over 20 years. Then in red on the scale on the

right is the annuity each £10,000 buys you, declining slowly. Then on the same

scale in green is the annual pension you can buy.

Now

in 1980 very few people paid into a pension. Retirement annuity schemes as they

were called then were quite rare. But then they were a very good idea. So James

was ahead of his time. But when Jonathan started his pension we were right in

the middle of the pension mis-selling scandal. That was when people were being

encouraged to pay into pensions. Set yourself free from the state we were told.

So there are far more Jonathans than Jameses.

And

Jonathan was putting quite a lot into his pension. £100 a month would have been

considered a very good sale in 1990. But all he got was £2500 a year – non index

linked – for life. That is barely half the basic pension he will get from the

state for his working life.

And

now we are heading for a state sponsored pension mis-selling scandal – or we

could be. I refer to the national workplace pension scheme which is of course

known by the initials N E S T. And yes it does have an egg as its symbol. And

it’s been trade marked just in case anyone wants to steal it! Mmmm.

And

let me clarify one thing here that I have been guilty of getting wrong. There

are two parts to this new pension arrangement.

First there is the law about auto-enrolment. That means that eventually every

employer will have to enrol all employees into a pension scheme. Now that can be

their own scheme if they have one, a new scheme if they want to create one, or,

as a default, into the second new thing – the National Employment Savings Trust

– NEST. But the minimum contributions that have to be paid into NEST are set

down by the Government. Spo the two things are separate – NEST as the default

pension but laws about who contributes and how much.

So

how much is that? First let’s see how much people contribute into pension

schemes now.

The

latest figures from the Office for National Statistics – which in fact were

published a year ago and relate back to 2007 – show that if you are in a salary

related pension scheme in the private sector then the amount paid in is about a

fifth of your pay 20.5% and this is shared between the employer who pays in more

than 15% and the employee who pays in on average about 5%. And that is the sort

of money that is needed to buy a pension of around 50% or so of your pay when

you retire. That’s why employers pay in that much – because they are

guaranteeing that pension. And that’s one reason why private sector final salary

schemes are getting rare. Often they are now called defined benefit or DB

schemes to help people not understand them even more.

If

you are in the other sort of pension, a money purchase or pension pot scheme

where your contributions are just saved up and you buy your own pension – like

James and Jonathan – then the amounts going in are far less. The total going in

less than half – a total of 9.2% with 6.5% by the employer and 2.7% by the

employee. Half the contributions half the pension is a fairly good rule. So

these pensions are not as good. And indeed when employers change from a scheme

that guarantees your pension to one that doesn’t they typically cut their

contributions dramatically. So taking less risk and paying less in.

And

what now for the new national workplace pension scheme that will start – sort of

– in October 2012? Now if you listen to the government you will be told it is 8%

going in altogether, just slightly less than the 9.2% average. And you will be

told that the amount is split 3% from the employer and 5% from the employee. In

fact you will probably be told that the employee’s contribution is 4% with an

extra 1% from the taxpayer. That is true but disingenuous because that is also

true of the 9.2% contributions – the 2.7% paid by the employee is partly

subsidised by the taxpayer.

But

there is another more important deception in these figures. Before we look at

that notice that although the total doesn’t look that much less than the average

outside this scheme the balance of contributions is reversed. The employee is

paying almost twice the contribution and the employer is paying less than half

the average.

But

the truth is even worse than that. Percentages can be misleading. 100% is more

than 60% but 100% of nothing is less than 60% of something. And the percentages

here are not applied to the whole pay but to a band of earnings. Now we don’t

know what those will be in 2012 but the figures given for 2006/07 were between

£5035 and £33,540. So we have to apply those percentages to that band of

earnings. So it is a much smaller proportion of your total earnings. The most it

can be is not 8% but just under 7%. And the least it can be is nothing but for

someone on median earnings it is about 6.4% and for someone on low earnings

which is the target audience for this pension, it is about 5% and barely 4.5%

for someone on minimum wage.

So

under the new system contributions going into the scheme for its target audience

– low paid people – will be a quarter of what goes into a decent salary related

scheme and a half what goes into an average money purchase scheme. And notice

too that the contribution by the employee is actually higher – because the

employer has got off paying in the bulk of it.

Even the Office of National Statistics observes on its website

Employers in 'not contracted out' defined contribution occupational pension

schemes with 12 or more members contributed 6.0 per cent of salary in 2007 –

more than twice what they will have to contribute as a statutory minimum from

2012.

Now

add to that – or rather subtract from that – the 2% upfront charges announced

this week – now that 2% of 8% so it reduces it to 7.84% – and the fact that the

start will be delayed not just to October 2012 but it will be phased in over six

years. For the four years these contributions will actually be 2% of that band

of earnings – 1% from the employer and 1% from the employee. And during these

first four years employers will be staged into this scheme – large to medium to

small so some may not in fact start even that level of contributions until 2016.

Once all employers are phased in by October 2016 the contribution level will

rise the next year to 2% and 3% and then finally from October 2017 to 3% and 5%

– nominal; in fact a lot less. And this table you won’t find set out like this

anywhere – I got it this week from the DWP.

Indeed for many on the contributions set down and with realistic projections for

the index tracking stockmarket funds that most people will be invested in will

not be enough to take them off or far off the means-tested benefits they could

get anyway. Some cynics believe the whole scheme is designed not to make sure

people are better off in retirement but that they simply pay in advance for the

equivalent of their own means tested benefits.

Well. I am aware that I am all that stands between you and your comfort break.

So I’ll just conclude before taking questions by saying that personal finance

education is not about investment or the importance of saving or the value of

pensions. It is about understanding arithmetic and its intersection with sales.

Warning young people not just about the shark infested waters of the financial

services industry but also of the Government propaganda machine that awaits

them.

Thank you.