This talk was given 23 February 2010

The text here may not be identical to the spoken text

ASSOCIATION OF CHARITY OFFICERS

I’m

Paul Lewis a freelance financial journalist, although best known I guess for my

work presenting Money Box on Radio 4. But I also write the money pages in Saga

Magazine and write for its website.

I

am very glad to be here and again am was astonished at the range of benevolent

organisations that belong to the Association. I was pleased to see one of your

members is the Bankers’ Benevolent Fund – or Her Majesty’s Treasury as it’s now

known. The only charity where you round your application up to the nearest

billion. I also like the charity for Cooperative officials – I don’t meet many

of those in my profession. And the Commercial Travellers Benevolent Institution

– that must be an easy job – just wait for them to come knocking at the door.

Let

me start with politics. All parties agree that we need to reform the way that

care is provided for people as they age but don’t die. We all agree that ageing

without dying is a good thing. We all agree that care should be provided for

people in that phase of life. And when it comes to who will pay – then again we

all agree – someone should. But ‘who’ is where the consensus breaks down.

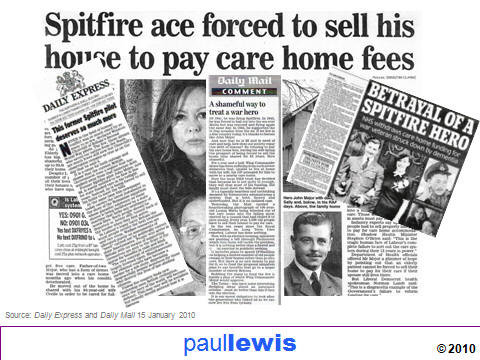

Here is the Daily Mail’s take on it

this week. Note the phrase ‘forced to sell their home’.

The

Conservatives say that if we all pay £8000 at 65 then the cost of care, should

we need it, will be free for life. But that is a little disingenuous Because

most of us never need residential care and of those who do most get it free

anyway. If you have continuing medical needs then the NHS pays without a

means-test. And if the NHS does not pay then if your assets are below £14,000

(England; Wales £19,000, Scotland £13,000, NI £13,500) then the local council

pays. So the invitation is to pay £8000 at 65 to get something free which you

may well not need and would probably be free anyway.

For

most people affected by that rule it is the value of their house or flat which

might take them above that level – average house price is around £165,000. And

it is that fear which leads to headlines such as this in the

Daily Express a month ago.

Spitfire ace forced to sell his house to pay for care home fees

The Daily Mail joined in and both had

trenchant editorials and copy such as “Labour’s betrayal of the elderly was laid

bare yesterday as a hero Spitfire pilot faced having to sell his home to pay for

residential care”

Now

the rules are complicated and I suppose I shouldn’t blame fellow journalists for

getting them wrong.

But

in case this topic ever comes your way – as I am sure it will in grant giving

charities – here is what you have to remember.

No-one, ever, can be forced to sell their home to pay for their care.

Why?

1. If you leave behind a spouse or partner living there then the value of the

home is completely ignored.

This Express story fell at this first

hurdle as 88 year old Mr Mejor did leave behind a wife Cecile. That was

dismissed by the Express in para 13

as ‘a glimmer of hope’. Never let the facts get in the way of a good story!

2. If a relative aged 60 or more lives

there then the value of the home is completely ignored. Mr Mejor’s daughter

Sally aged 54 lives in the house as a carer for her mother. So if the

94-year-old Cecile survives another six years, the house will not count even

when she dies.

3. If someone who acts as a carer lives there then the local authority has the

discretion to ignore the value of the home.

So

the Express story could fail there

too – even if Cecile dies before Sally is 60.

But

suppose that doesn’t happen – no spouse, no relative over 60, no carer, an empty

house or flat?

It

still doesn’t have to be sold.

For the first twelve weeks in the home the value of the home is ignored. And

after that there can be a

deferred payment agreement. Introduced in October 2001 this agreement allows the

resident not to pay for their care at the time. Instead the bill clocks up every

week but nothing is paid. Instead the local authority takes a legal charge on

the home so that when the person dies or the home is sold the care bill is paid.

The care bill is added up each week without interest being charged. So it is an

interest free loan. No interest is charge until 56 days – 8 weeks – after the

person in the home dies.

And

of course while that is happening the property can be rented out or lived in by

a younger friend or relative to keep it in good order.

The income from that can be used to pay the care home fees.

In

this way the amount lost on death from the value of the home can be minimal.

Now

not all local authorities offer deferred payment agreements – though they

should. They were reminded in England in April 2009 that if a council did not

then “it is likely the courts would find this to be unlawful”. Similar rules

apply in Scotland and Wales.

[LAC(DH)(2009)3

para 15]

But

what if Cecile dies, daughter Sally is still under 60, discretion isn’t

authorised, and the council does not offer a deferred payment agreement will Mr

Mejor have to sell his home?

No.

Under the National Assistance Act 1948 the local authority has to provide

accommodation for elderly people who need care. And that obligation is not

extinguished if the person receiving the care refuses to pay for it.

The

procedure in those cases is set out in s.22 of the Health and Social Services

and Social Security Adjudications Act 1983 – usually known as HASSASSA. It says

the local authority has to place a charge on the Land Registry against the value

of the property but cannot charge interest on the debt while the person is

alive. And the only real difference is that interest is charged from the day

after the person’s death rather than waiting for 56 days.

So

even without a deferred payment agreement the debt can build up interest free

until the resident in the care home dies.

You

just have to be firm. But if you are, no-one has to sell their home to pay for

their care.

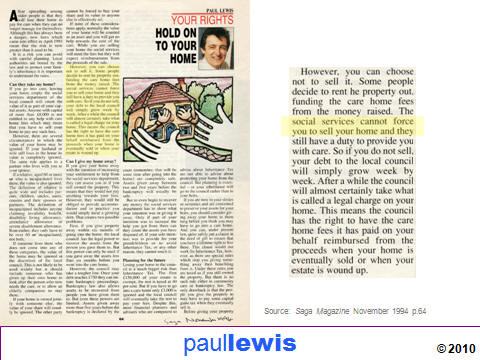

I

find all this particularly frustrating because I wrote about it in an article in

Saga Magazine in November 1994 where

I set these rules out. I called it ‘Hold on to your home’.

Here it

is. And here is what I wrote then. – “They cannot force you to sell your home.”

And the rules have not changed since then – unlike the photograph.

So. No-one ever can be forced to sell their home to pay for their care.

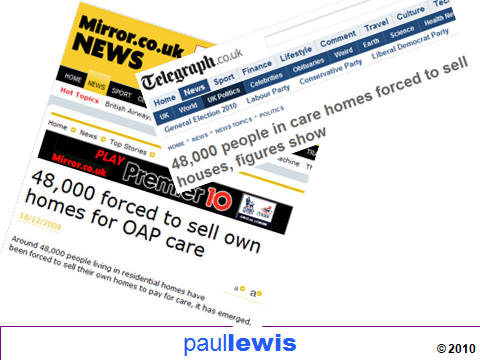

But here is The Daily Telegraph a

couple of months ago.

And the Mirror of the same day

So

where does this figure come from? And what does it really mean?

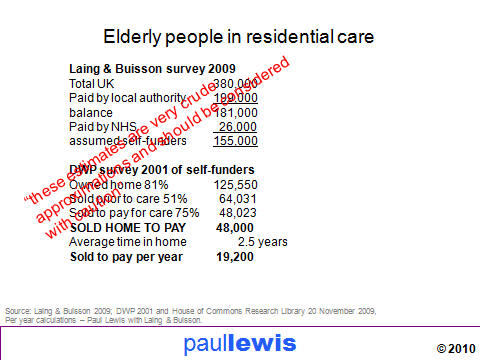

It comes from two sources. First is an annual survey done by the health analysts

Laing & Buisson. Each April year it does a survey of all the people in care

homes in the UK. And it found in April 2009 there were 380,000 elderly people in

care homes.

Of them 199,000 were paid for by the local council,

another

26,000 were fully funded by the NHS. L&B assumes that the balance of 155,000 is

the number who pay for themselves – self-funders. We don’t know they’re

self-funders they are just a residual number.

But

how many of those sold their home to pay for their care?

Now we need other research and the only one was by the DWP in 2001. It found

that of those who paid for themselves 81% owned or had their own home

Of those 51% just over half had sold their home prior to entering care

And of those who had sold their home three quarters had done so to fund their

care.

So you finally come to about 48,000 people in a care home in 2009 who had sold

their home to pay for it.

Now, as the House of Commons researcher who did this calculation says in her

note

“these estimates are very crude approximations and should be considered with

caution”.

There are two things to note about them.

1.

There is no evidence whatsoever about how many of these 48,000 people were

‘forced’ to sell their home. They may have done so to get better care – a room

of their own, a room with a view, a room in a home that the local council

considered too luxurious.

2.

This is the number of people in care in 2009 who had sold their home

at some time in the past to pay for

it. But it is widely misquoted wrongly as being the number of people who have to

do that each year.

The average time in a care home is two and half years so if 48,000 in care homes

had sold their home one can sort of say that the number selling their home each

year is 48,000/2.5 = 19,200. About one in twenty of those in a home

But

remember these figures depend on a sample survey done in 2001. At their best

they are flaky.

But

big figures are very attractive to politicians trying to say as they do that

Labour has betrayed thousands of pensioners. Liberal Democrats and Conservatives

have used the figures to say 45,000 (which was the 2008 number) people

every year have to sell their home

to pay for their care. That is simply false.

So

about 19,000 people a year probably sell their home to pay for their care but

they did not have to. And remember that most people never go into a home –

perhaps one in five of us does, it may be less. And of those who do about one in

twenty sells their home to pay for it. One in a hundred of the population.

People like my neighbour Margaret. She was in her eighties and had two hip

operations neither of which worked well. Using a zimmer frame, struggling up and

down stairs and then dementia began. She sold her house to pay for her own care

near friends, by the seaside and got a much higher standard of care for the

eight months she lived than if she had struggled to get the council to provide

her with something suitable in London. She is one of those 19,000 who sold their

home to pay for their care in 2009. I am very glad she did. And I am sure she

was too.

But

the parties are now discussing who should pay for the care for those living

longer lives.

Conservative plans involve a voluntary payment of £8000 at the age of 65. It’s

an insurance scheme. And it would only pay for the same care you get now. And

it’s not to provide free care – because if you have no available assets you get

that anyway. But to protect your estate. So the financial beneficiaries are the

heirs not the person in care.

And

then of course there is the Labour scheme.

Care

will be paid for by a death tax of £20,000 according to the famous Conservative

poster. Well it might be. The consultation Green Paper published last July says

that someone of 65 will probably need £30,000 worth of care before they die.

That includes care at home as well as care in a home. Whereas the Conservative

plans are just for care in a home not prior care at home, hence they are cheaper

than Labour’s and voluntary.

And

the £20,000 death tax was sort of mentioned in that Green Paper.

Option 3, the insurance option, says

“after

their death…

£20,000”

Option 4 says

“£20,000…after

their death.”

So

that is where the £20,000death tax comes from. And a death tax of £20,000 from

everyone who owned a home on their death would raise about £8 billion a year.

Which is comparable to total council spending in England on personal social care

for people aged 65 and over which the Audit Commission tells us was £9.1 billion

in September 2009. (National

Adult Social Care Information Service, Personal Social Services Expenditure

and Unit Costs, England Provisional 2008/09, NHS Information Centre,

September 2009. Cited in Under Pressure

Audit Commission February 2010).

But

now I am told that when the Government announces its plans – probably in March

which is enough time before the election to influence it but not enough time of

course to actually change anything – I am now told by the Dept of Health – in

the name of Andy Burnham Sec of State for Health

“No

decision has been made yet on how this necessary reform will be funded, but a

£20,000 flat fee after death is not an option we are considering.”

So

the poster worked.

Because for reasons I have never understood Inheritance Tax is just about the

most hated tax – second only to council tax.

I write guides to Inheritance Tax – how it works, how to reduce it and so on. But I always start by saying something like this –

why is

it hated? it is due when you are dead. Someone else pays it. The ideal tax for

me.

That’s from my book Pay Less Tax 2010

due out later this year from the charity formerly known as Age Concern whose new

name Age UK is still a secret.

Now

if there was a new death tax to pay for care then (a) and (b) would certainly

still be true – when you are dead and paid by someone else. Though (c) would

probably not be as about 70% of the retired population own their home and just

about all of them have that much equity in it. Hence the income of £8 billion a

year from a flatrate death tax of £20,000.

But

(c) currently is true – and even more so since the Chancellor made the

Inheritance Tax allowance portable from one married or civil partner to another

in October 2007. Couples with assets of less than £650,000 need not worry about

Inheritance Tax.

Here are the figures. In 2008 nearly 580,000 people died in the UK. And in

2008/09 16,000 estates paid Inheritance Tax. That is less than 3 estates in 100.

In fact it is one in every 36. In other words out of 36 funerals you see only

one of those families in black will have to worry about Inheritance Tax. It is a

minority concern.

But

even those who do pay it shouldn’t care. Not just because they are dead. But

their heirs shouldn’t care. Almost all those people who do fear they will have

to pay the tax should realise it is due not on money they have earned or saved.

It is due on a windfall gain on the home they live in.

If you are 80 now and paid off your mortgage at 65 and bought that house at 50.

Suppose that home is now well into the IHT band. Suppose it is worth £500,000 –

now for most people who are or have been a couple no tax will be due on that.

But if you are single or haven’t arranged your affairs sensibly then tax may be

due. So let’s ignore that fact.

If it is worth £500,000 now and you bought it 30 years ago it was then £67,750.

Now you may have struggled to pay that mortgage off over the next 15 years –

average pay then was around £4,100 a year. So it was about 16.5 times average

earnings. But you managed it. Today that house is worth about 20 times average

earnings - £500,000. So you have a windfall gain of £432,250. Money you haven’t

earned in any sense of the word. And even if you take account of the cost of

borrowing most of that money the windfall is still nearly £400,000.

That has been created by inflation, by wage rises, by the economy of the

country, by the state you live in. So why shouldn’t the state take some of it

back? £20,000 a twentieth of the total. In many countries that capital gain on

your home would be taxed while you were alive. Here it is not even taxed on

death.

And

while we are talking of inheritance tax can I tell of another thing that really

annoys me. And this time it is what charities do.

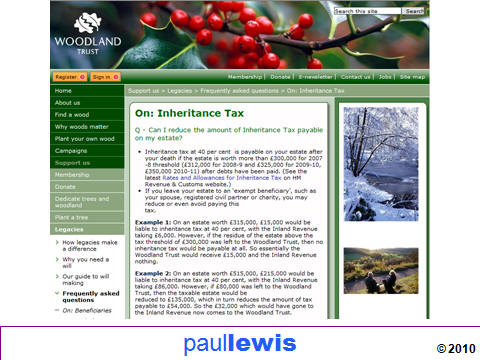

Here is the Inheritance Tax page from the Woodland Trust website – I pick that

because it’s the first I found – but there are dozens of them.

Let’s look at Example 1 in more detail.

That is true – but misleading. Suppose you left nothing to charity?

£15,000

would be liable to IHT and taxed at 40%. So of that £15,000, the Revenue would

get £6000 and your heirs £9000.

If you

leave £15,000 to the Woodland Trust then the Revenue gets nothing out of that

£15,000 but nor do your heirs! They get £9000 less of your estate. So in fact

the heirs make a bigger donation to the Woodland Trust than the person who has

died.

Now

it is good to leave money to charity. And I know a lot of you depend on it. But

it is not a tax planning technique. It is better for your heirs to have 60% of

something than 100% of nothing.

So

please in your desire to raise money in wills don’t mislead people like this. It

is one of those financial pitches that is true but misleading – indeed it is

worthy of the financial services industry itself.

And

talking of which, I have been shocked this month to discover that the annual

cost of policing the UK financial services industry and compensating customers

when things go wrong will top £1 billion for the first time in 2010/11. That is

more than £20 for every adult in the country. And we all pay it through the

price of insurance, loans, mortgages, investments, and banking services –

including the low rates on savings accounts.

Almost half the money – £455 million – is needed to pay for the expanding

Financial Services Authority. It is taking on 460 extra staff – in addition to

the 280 extra recruited this year. The FSA has already announced it will have to

pay its staff more money to recruit and keep the quality people it needs.

Since

it began to be fully operational in 2000 the cost of the FSA

has

rocketed from under £200 million to a forecast of almost £500 million in the

coming year. One reason is that it now regulates more sectors – insurance and

mortgages have been added – and it is now expanding further to make sure its

supervision of banks is rather better than it was before the 2008 crisis.

Slightly more – £505 million – will pay for the Financial Services Compensation

Scheme. It coughs up when people lose money due to regulated firms going bust.

About three quarters of this money is interest on the £20 billion which the

Treasury lent the scheme to ensure savers got all their money back when five

banks and one building society went bust in the crash of 2008. No-one knows when

or if the capital will ever be repaid but the interest has to be repaid

annually. That cost is about £375mn and the rest, say £130 million, is the

estimated cost of direct compensation for other failed firms.

Add on nearly £114 million to run the Financial Ombudsman Service and almost £33

million for financial capability – which will soon be the responsibility of a

new consumer financial education body – and the grand total comes to £1.1

billion. All of which will be added on to the price of the financial products we

buy in 2010/11.

But

hang on! Did I just say £33 million for financial capability? Out of more than

£1 billion to police the financial services industry and compensate customers

for its mistakes? In other words what is being spent on helping us to understand

the complex products which the industry sells is just 3% of the total cost of

putting things right?

I

did. And in my view far too much. When I spoke to some of you last year I

expressed this view:- I am against all this effort being put into financial

capability.

How

can I be against helping people understand their finances as a way of managing

them better. Surely everyone is in favour of that?

Of

course I am not against people understanding their finances and being sceptical

about the offers they are made by banks and financial companies – as they should

be sceptical about any retail offers. I spend almost all of my working life

trying to help people understand money and the way financial companies operate.

But thinking that financial capability is the answer to the financial

difficulties of low income households is simply a mistake.

Now I am going to take some facts and a clip from a programme made by my

colleagues on Woman’s Hour and broadcast just over a week ago. The programme

began with this question

What is 1.12 x 2.2

It

was we were told a question an 11 year old should be able to answer. But a fifth

of adults have numeracy skills below those of that 11 year old. And adult women

are more likely to have poor numeracy than adult men – a third of women say they

struggle with maths. And a third of parents say they avoid helping their

children with their maths homework because they feel incapable.

The

programme then played this selection of women asked are you good at maths?

And

indeed what is 1.12 x 2.2?

2.46

The

reason the banks make money – and yes even now the retail bits of the banks are

highly profitable – Barclays for example, between retail banking and Barclaycard

it made £1.4bn in 2009 on a turnover of £8bn. Those figures were a lot down on

2008 but still not at all bad in a tough year.

And

the reason they make that money is because they are better at arithmetic than

the rest of use. And no amount of financial capability training is going to

change that. It is like trying to give everyone tennis capability so they can

stop losing money when they play Andy Murray. It is not going to work.

And

the only reason people need financial capability is because the products they

are sold are complex, the descriptions of them are misleading, though true, and

some of them are dangerous.

It is part of a process which I call complexification. Making financial services

so complex that the human brain cannot make rational choices, ends up making bad

ones, but usually doesn’t even understand what it has done wrong. And if it does

work it out and complain it is referred to paragraph 94(a)(i) blobby point five

which, somehow, they failed to read and understand before they bought the

product.

So

financial capability is a problem for the financial services industry not for

the consumer. If we accept, even for a moment, that it is the confused who are

to blame rather than those who are confusing them, we turn mis-selling which is

rife and an embarrassment for the industry, into mis-buying which lets them off

the hook if they put a few pounds – OK £33 million – into a financial capability

programme.

Rather what we need is tough regulation, not of process but of products. Not of

how things are sold but of what is sold.

I bought a car the other day. And I was faced with a choice. Toyota or a car

with brakes that work? No. Actually I did buy a Prius – some controversy over

how it is pronounced. Prious Preeus. I go with Prious – rhymes with Pious –

because they do come with smugness built in? The car in front is a Toyota – why?

Because its accelerator is stuck on and its brakes don’t work. What colour would

I like – maybe metallic paint? Did I want a sporty number with two seats? Or a

family vehicle that could fit a table and a dog in the back? How about built in

sat nav? These are all valid consumer choices.

But

if this had been sold by a financial adviser I would have been asked what

tensile strength glass did I want in the windscreen? It all depended on my risk

reward ratio. Plain window glass was clear, you could see through it probably

better than normal windscreen glass. And it would cost me a lot less. But there

was an outside chance that a stone might hit it and then it would break and

shower me with razor sharp glass shards? What was my risk profile?

Luckily it was a car. I didn’t have to search the internet for information about

the brake linings you needed for a 1.8 litre engine. I didn’t have to decide

where I wanted air bags. All those things are laid down. In the law. The car I

bought will be safe. It is illegal to sell one that isn’t. So I didn’t have to

have to take a vehicle literacy course so that I could make rational choice

about the car I bought. I was allowed to make the choices that a customer

can make – colour, fuel consumption,

upholstery. And of course if there is a fault found – it is recalled and mended

free – as 8 million Toyotas are being this month.

But

imagine if the sale of cars was regulated by the Forecourt Sales Association –

FSA for short. it would be perfectly happy if I

was sold a car with a windscreen

made of window glass. As long as the risk was explained to me in paragraph 94

(b) (ii) blobby point five. ‘In some circumstances window glass can shatter.’

You were warned.

That’s because the FSA regulates not products but process. As long as an item is

sold correctly and the risks explained then it does not have to fulfil any other

standards.

Now

I made up the Forecourt Sales Association. But there is another FSA and it does

regulate products. And it does tell us who is doing what.

17

August 2009 Shutki Raja Chutney Powder. The FSA has issued a Food Alert. Local

authority food law enforcement officers must make sure the chutney is withdrawn

from sale and destroyed.

No

problem was found with Shutki Raja Chutney Powder. Except that it had been

produced on unregistered, or possibly unapproved, premises. So the product was

named and withdrawn and destroyed.

17

March 2009 Active brand peanut butter has been found to be contaminated with

excess levels of aflatoxins. The Agency has issued a Food Alert. If any of these

products are found, enforcement officers should ensure they are withdrawn from

sale and detained.

It’s a great job isn’t it? What did you do at work today? I detained a jar of

peanut butter.

Compare that with its namesake that regulates financial products. Aflatoxin in

peanut butter. It would immediately swing into action and order a thematic

study. And a spot of mystery shopping. After some months it would publish the

results calling on the industry to take action to explain clearly to customers

what aflatoxins were. After giving the industry several months it would order a

second round of thematic work and a bit more mystery shopping. The next year it

would publish a review and ask for comment. A few months later a Consultation

Paper would appear on how these ingredients should be described and discuss

whether they were ever completely inappropriate. A few months after that it

would publish the results of the consultation paper setting out what it planned

to do. Food manufacturers could object. It would then issue a feedback statement

with a draft a timetable to make changes in the rules. And six months later

decide that more time was needed as otherwise there was a real danger than

peanut butter would not be available for everyone’s sandwiches and that changes

would not be ordered until 2012.

Meanwhile the businesses that had been found to be selling food contaminated

with aflatoxins would not be named. Their identity would be kept secret from

consumers. So the FSA would know who was selling dangerous food and under what

brand names. But it wouldn’t tell customers.

Much better to be like the Food Standards Agency – ban them. Issue a notice and

destroy them. ‘My goodness’ I am told ‘we can’t work like in the finance

business! If we went round banning things it might destroy confidence in the

industry. Then no-one would buy pensions or investments. And that would be a bad

thing – wouldn’t it?’

Among that list of products reported by the Food Standards Agency recently there

was this

20

November 2009 Tesco has withdrawn two batches of its own-brand wholegrain brown

rice because they might be contaminated with insects. The Agency has issued a

Food Alert for Information.

12

November 2009 Coca Cola Hellenic Bottling Company has withdraw certain batches

of Dr Pepper in Nothern Ireland, because of high levels of benzoic acid.

Big

brands. Named. Does it stop people shopping at Tesco? No. Does it make give up

their Dr Pepper addiction? No.

Rather we buy food with confidence because we know that the Food Standards

Agency is there, naming products, withdrawing products, detaining jars of peanut

butter and ultimately banning and destroying products.

That is my vision for the future of financial regulation.