Charles Ponzi (1882-1949)

This talk was given 25 November 2008

The text here may not be identical to the spoken text

MONEY ADVICE LIAISON GROUP

ANNUAL MEETING 25 November 2008

20 YEARS OF TALKING DEBT –

WHO HAS BEEN LISTENING?

Hello. Well after that introduction you are probably thinking who? I am a freelance financial journalist and have been for more than twenty years. And I do present Money Box on Radio 4 which is probably where you know me or know the voice anyway.

Money Box of course is cutting edge journalism. On the 4 October after press speculation about the safety of Icesave the UK branch of the Iclenadic bank Landsbanki. We swing into action and got its Managing Director Mark Sismey-Durrant onto the programme. I asked him ‘So UK customers of Icesave can be sure there money is safe and they can get it out when they want? ‘Yes’, he replied, they can be’.

I am told the run on the bank started at that moment.

But this leads me on to my answer to the question posed by this talk Twenty years of talking debt – who has been listening? And my depressing answer is ‘not the people who should have been.’

Not the banks

And let’s start

with the first – not the banks

Until recently the banks were in positive mood weren’t they? If the problem of debt was raised with them, it was seen as a matter of consumer choice. As long as the conditions of loans were explained clearly – and hadn’t they just introduced summary boxes for personal loans? – then regulation was not needed. It was a case of caveat emptor – let the buyer beware – before they take on a loan.

A motto they could have adopted themselves. In order to see what has happened to the banks, I’m going to start by taking you to Colombia.

Ten days ago the Colombian government promised to reimburse at least some of the tens of thousands of its citizens who have lost their savings to a widespread con trick. The final bill could be hundreds of millions of dollars though the Government may now only give back money it has seized from the crooks and will concentrate on those with the lowest losses. The scheme was called

Dino Rapido Facil Effectivo

or in English

Easy Money Fast Cash

And it was. For the crooks who perpetrated it. The scam they used is named after Charles Ponzi who stole at least $10 million – probably a lot more – from thousands of Boston residents in 1920.

|

|

|

Charles Ponzi (1882-1949) |

He didn’t invent the scam. In fact he discovered it when he worked in a bank – the Banco Zarossi in Montreal. It offered depositors 6% return on their money, which was double what other banks were paying. Banco Zarossi grew rapidly and invested some of its money in property – houses and so on. Those investments went bad and the bank’s owner started paying the investors their 6% by using the money from the new investors. The bank went bust and the owner fled with a lot of investors’ deposits.

Charles Ponzi learned a valuable lesson. The way to make money is to con people. And he developed the scheme that has come to take his name. Though in fact it could be the oldest investment con in the world. But tricks grow old because they’re good.

It works like this. You claim insider knowledge which will enable you to make a very high return. You offer to invest money in it for your customers. And promise them huge returns on their money. In Ponzi’s case it was like the carry trade – the price of international reply coupons varied from country to country so you bought them where they were cheap and sold them where they were dear. Ponzi offered investors 50% after 45 days – which is about 2780% a year. In Columbia people were offered amounts variously reported to be between 70% to 300% over various periods. Greedy investors pile in and at first they do get paid. Seeing the massive returns their friends, neighbours and relatives all put money in too. One man invested £3000 after his wife got an 80% return. Some of them get paid out for a month or two as well.

But there is no real insider knowledge. No sensible investment. And no miraculous returns. People are paid using the money deposited by new investors. Pretty soon the payments stop. The scheme collapses under its own weight. And the thieves make off with the proceeds. In Colombia over the last couple of years many of the crooks seem to have got away with it. In October one gang in Cauca province in South west Colombia left a note on the door of their abandoned premises “Dear investors, thanks for trusting us and depositing your money.” Another said more honestly “You stupid suckers. We’re out of here. Thanks for believing us.” Or maybe they’re just two translations of the same Spanish.

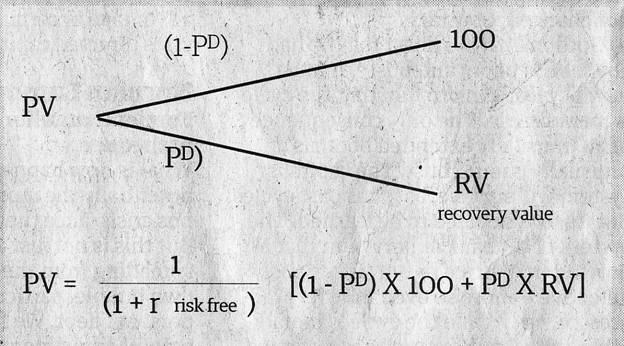

If this 2008 scam in Colombia rings a bell, consider this. A bunch of determined and clever people persuade investors that mortgages have been wrongly priced. High risk loans can be turned into much more valuable low risk deals using a magic process called collateralised debt obligations. The formulae are impressive – this one from J P Morgan.

The returns are high. And the people who sell them get wealthy and successful. So more and more people pile in. Eventually much of the world’s banking system depends on these complex instruments doing what they promise. But the payouts are in fact being made by borrowing more and more money. And the assets the scheme is secured on start falling in value rather than rising.

But the global Ponzi scheme is now so big and the potential losses so incalculable that governments around the world step in. Ordinary savers are told their money is safe. And the money that never existed is replaced with tens of hundreds of thousands of millions of dollars – certainly five trillion dollars and probably £5 trillion. All borrowed of course from future taxpayers. The perpetrators are not prosecuted and keep most of the money they have creamed off.

Charles Ponzi may have died in Rio de Janeiro in 1949. But his ghost does not just haunt Colombia. It stalks Wall Street. And it whistles in the City of London.

But there is one big difference between Ponzi schemes as we usually see them – such as the current scam in Colombia – and the credit crisis that his struck the world’s banks. In Colombia crooks were targeting poor but financially ignorant members of the public. With the credit crisis the banks targeted each other.

It is called securitisation. Turning an income stream into capital and then using that capital to generate another income stream. It’s what banking has done since the Medici family invented it in Florence in 1397 – six hundred years ago and three hundred years before the Bank of England was founded in 1694. Done properly and honestly securitisation works. But because the maths is fairly complex it is easy to fool people.

Now I’m not going to go into securitisation. But all the complex maths involved in the current securitisation models called credit derivatives, mortgage backed securities, and collateralised debt obligations, only works if somewhere you lie about the risk. Think about it. You have very risky loans because you have expanded the market too far. You sell them as safe loans producing less income but worth more and pocket the difference.

Or look at it this way. The whole system was predicated on rising house prices. And what made house prices rise? Demand. And what kept demand growing easy credit. And what kept credit easy? Rising house prices. Mmmmm.

Now if you’re dealing in trillions (when Lehman brothers went bust the administrator of the London office said it had £30bn passing through its doors every day – that is £1 trillion a year and that’s jut the London office of one middle sized investment bank) a small fraction of one percent can create a very nice income not just for you but for a whole industry of tens of thousands of middle men and women – arrangers, depositors, asset managers, maybe guarantors, perhaps trustees, all well paid. But to generate all that money at the heart of this process someone – perhaps everybody – has to be misled about the risk.

It’s financial alchemy – turning base loans into gold. It’s like solving global warming by inventing a perpetual motion machine. It would work – but it can’t. In fact designs for perpetual motion machines go back to much the same time in Europe as banking was invented, to a man called Villand de Honnecourt in 1360.

The real reason why the banks have stopped lending to each other. The real reason why the whole banking system reached the brink of collapse is because the banks don’t trust each other. And they don’t trust each other because they have been lied to about risk. And they know they have been lied to because they’ve been lying themselves.

Now I’ve got into trouble for using the word lying about this. And people have said it might be misleading, it might be misunderstanding they say. Is there any proof they were lying, they ask, that they told an untruth and knew it was untrue. Well, maybe not. But they certainly described the risk with a reckless disregard for the truth. Which to me is as bad.

But whether they were liars or too dim to understand or too careless to get it right perhaps they are not the people who should have been in charge of all the money in the world for so long.

So now the banks have gone to Governments and said ‘look. We made a mistake. We got it wrong. We didn’t mean to. We can’t afford to pay it back. Can you let us off?’

Those of you who deal with people in debt know the kind of answer the banks would give – and are still giving – to their customers who come along with that sort of plea. But the banks are so important we have bailed them out with £5 trillion – as much as the entire world produces in nearly two months.

£5,000,000,000,000

Annual global GDP

£35,000,000,000,000

And it has gone to rescuing or nationalising or allowing to go bust more than 50 banks. Some like Citibank appear twice the first $25 billion rescue was not enough. Now it has been given another $20 billion of capital and had $306 billion of its dodgy loans guaranteed.

So it seems that caveat emptor applies to individuals who borrowed too much on exaggerated security. But not the banks who borrowed too much on dodgy security.

And in the UK in exchange for a total commitment of £500 billion the banks are saying ‘we don’t want to do anything for it. Because it would be completely wrong to interfere with the way we do banking. After all we’re the only ones who understand it.’

The money that is getting the most attention is the £50 billion for the capital of the banks. And £37 billion of that has already been committed to boosting the capital of Royal Bank of Scotland, Halifax Bank of Scotland (HBOS) and Lloyds TSB.

Those last two banks of course are merging, or in fact LTSB is taking over the much bigger HBOS. That deal would normally have been blocked by the competition authorities. The Office of Fair Trading made it clear four weeks ago that

there is a realistic prospect that the anticipated merger will result in a substantial lessening of competition in relation to personal current accounts (PCAs), banking services for small and medium sized enterprises (SMEs) and mortgages OFT Report on Lloyds/HBOS merger 31 October 2008

Despite that the deal was waved through by the Business Secretary Peter Mandelson. He said earlier this month the merger would preserve “the stability of the financial system” (Daily Express 1 November 2008).

As part of the deal HBOS will get £11.5 billion and LTSB £5.5 billion from taxpayers to boost their capital.

In exchange the Government has said it wants mortgage levels and small business lending to remain at 2007 levels.

But Eric Daniels the Chief Executive of Lloyds TSB said on 3 November, when he was encouraging shareholders to vote for the deal, that the Government’s shareholding in his bank would not “have an impact on our lending policy”.

Though in fact all this is exactly the opposite of what you might expect. A year ago the banks were happily lending people 100% of the value of their home on five times their income. Northern Rock was lending people 95% secured on their home and mortgages and up to 30% in addition on an unsecured loan – the famous 125% mortgages that are now causing so many people so much trouble.

But you won’t find those loans now. And for the Government to call for their return is just nonsense.

Here is how mortgage lending has changed over the last year.

Source: MoneyFacts 24 November 2008

In November 2007 95% mortgages were nearly a third of the total 30.6%. That has declined quarter by quarter until today it is barely one in fifty – 2.1%. A similar fall for 90% loans down from around a third to about one in ten. 85% and 80% have grown in popularity. And 75% loans even more – they now account for a third of all the deals on offer. And just in the last couple of weeks 60% loans have begun to dominate the tables with one in five of the deals on offer now being for 60% of the home’s value.

And there is little wonder that LTVs are declining. In the past just as in the USA the banks didn’t care too much if people didn’t repay their loan because it was secured on an asset that was growing in value. And if worst came to worst that asset could be sold.

But this graph shows how dangerous that assumption has now become. It’s a bit complicated. But it shows the homes that will be in negative equity. It uses many assumptions so it is illustrative rather than definitive.

Source: Halifax house price survey October 2008

The black line shows the average house price now - £168,158 (Halifax – there are others but we’ll use this one. They all give similar results). Next let’s look at those who bought their home with a 100% mortgage. The last time house prices were at this level was September 2005 So anyone who bought a home with a 100% mortgage between September 2005 and now is in negative equity. What about a 95% mortgage? Here it is. Anyone in this area bounded by April 2006 and July 2008 is now in negative equity. Down to 90% - and those bought between February 2007 and April 2008 their mortgage will be worth more than their home. Even 85% borrowers who bought at the top of the market April to September 2007 will be in negative equity now. You need to borrow at 75% to be safely below negative equity.

But hang on a minute. Aren’t house prices still on the way down? Yes. And many people expect them to fall another 20%. That would take the average price down to £134, 526 – it hasn’t been that low since the middle of 2003. That’s the thick orange line which shows that value £134,526. Now you see that even 75% loans are in negative equity between April 2006 and June 2008. More than two years of home sales. And of course at higher LTVs negative equity – the area above the orange line – stretches way back to sales made in late 2003 and 2004. You need to go down to 60% LTV to keep all recent sales comfortably below that current value line. But another 10% fall would start to put those homes in negative equity too.

And that is why the best deals are confined to those with 60% deposits and why we saw earlier that as the proportion of 95% and 90% mortgages has declined, the proportion that lend 60% has started to grow. A year ago it was negligible at 0.6%. Now it is one in five. And that 20% of mortgages are the ones with the best deals – the lowest interest rates. If you borrow more than that you pay more to pay for the risk – not the risk that you will default. But the risk the lender bears that if you do fail to meet the payments and your home is repossessed the bank may not get all its money back.

So today the banks assume that the only safe loans are 60% of the value of the home and as the percentage lent increases the risk grows. Lenders are cutting back on self-certification mortgages and reducing the multiple of your annual income which can be lent. 3 times used to be standard, then it was 3.5 then it rose to 5 or even 6 in some cases. Now it’s back down to 3.5 or so.

Now the collapse in credit that we have seen is unprecedented, certainly no-one alive and at work today has seen anything quite like it. And the banks have reflected this by altering the loans they are prepared to make. They won’t make loans of 100% of the property value. They charge a great deal more for even loans of 85% of its value. They reserve the best deals for those borrowing no more than 60% of the property value.

But what attitude are they taking to the people who were lent 100% of the value of their home on a large multiple of their income? Are they saying fair enough we all thought that house prices would rise forever, we thought it you thought it, we will share the pain of what has gone wrong? No.

Northern Rock has specifically refused to take any responsibility for the 125% loans it offered people even though arrears of more than three months stood at 3.1% whereas the industry average was 1.3%. And although all banks say repossession is the last resort they are not holding back from that because they should never have lent these amounts in the first place.

In the USA some banks are looking to end foreclosures – repossessions – they are rescheduling loans that people should never have been made into something that is possible to repay. But the problem is they no longer own most of their mortgages – they have been sold on to investors who feel no responsibility to the people who are about to be made homeless.

The USA President Elect Barack Obama is proposing a 90 day moratorium on foreclosures for all banks accepting state aid plus 10 per cent tax relief on mortgages and new powers for the courts to amend the mortgage payments of people facing bankruptcy.

Yesterday in his Pre Budget Report Alistair Darling appeared to offer a three month delay in mortgage repossessions – though what difference that would make or which lenders would be involved is not clear.

“a commitment from major mortgage lenders on the [Lending] Panel not to initiate repossession action within at least three months of an owner-occupier going into arrears.”

Pre Budget Report 24 November 2008 p5

But it seems likely that the banks which have made these terrible errors will not be forgiving the borrowers. They will still ultimately be going to court to seek possession of homes which were sold on mortgages that they now know they should have offered. And when asked if they can still do that their only concession to the Obama agenda will be to shout ‘Yes we can’.

Now those of us who have been warning for some years that the banks’ lending policies were bad are not actually that upset that lending is getting more difficult and more expensive. It is probably very sensible for the banks to lend at reasonable interest rates and sensible income multiples. One person I interviewed on Money Box said we were facing a return to Quaker Banking. No-one knew exactly what that was but we all knew exactly what he meant. And I for one would not want the banks to go back to the 2007 levels of lending – you can only do that by lending foolishly.

But what the banks must do is to recognise that many people now their own personal credit crisis are there due to the lending policies of the banks. Policies which are now seen to have been reckless and foolish and based on impossible beliefs about the cost of money.

If the banks with their experts and their 600 years of experience got the price of loans wrong and sold them to us too cheaply and too easily, why should over-indebted customer bear the full price of those mistakes while the bank are protected – with taxpayers’ money?

So who’s listening? Not the banks but they have at least been forced into more sensible lending policies – at least on property – by the credit crunch they created by their foolish mistakes.

Not the Government

So if the banks

are not listening, who is? Not the Government.

There are two parallel crises going on here. There is the banking crisis, the global credit crunch crisis that is affecting the banks and the way they behave. But there is also the continuing problem of over-indebtedness by individuals. Of course the first partly caused the second. Because the Government has not been listening to these problems for 20 years. Indeed, in December 2003 in a White Paper setting out its policy on consumer credit in the 21st century it opened the document with these words

Consumer credit is central to the UK economy

Fair Clear and Competitive DTI Cm 6040 December 2003

And for some years the UK avoided a recession because people borrowed too much to keep spending in the shops. It was a conspiracy between the Government the banks and of course the general public.

Out of that White Paper came the Consumer Credit Act 2006 which does introduce some useful things.

One which gave people considerable hope was a new provision which was supposed to enable people to tackle very high APRs. Instead of proving that a deal was ‘extortionate credit’ which the courts had never used to put a limit on APRs – the new section of ‘unfair relationships’ was intended to deal among other things with extortionate APRs.

On the face of it the provisions could be tough. The courts can be asked to revise a credit deal if the relationship between lender and borrower is unfair to the borrower because of

any of the terms of the credit agreement

the way the lender has enforced their rights

any other thing done (or not done) by the lender

And the court can

Alter the terms

Reduce the amount payable

Order a refund

Remove any duty on the borrower

Make the lender take action

So it sounds tough. But because it does not mention APR there is no indication that APR alone would be considered by the courts to constitute an unfair relationship. And as far as I can ascertain no court case involving the unfair relationships test has been brought. So we still have deals involving APRs in the hundreds even thousands of per cent.

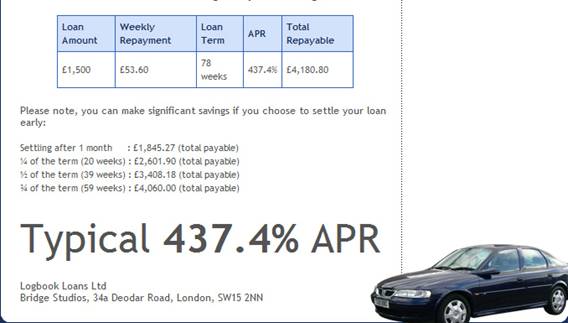

I was at an international conference on debt last week. And I shocked the audience there by showing them this.

Log book loans. The offer is simple. If you have a car you can borrow money against it from £500 to £50,000 secured on your car – as long as it is worth at least twice as much as the loan.

Loans4logbooks is a similar outfit. Now it says there the typical APR is 321%. But using the example given later it would charge 635.7% APR and if you want the loan in cash that can be arranged for a fee of 4%. That boosts the APR up to 798.9%

And then there are pay day loans – where you borrow money now and pay it back when you get your salary or wages. But because the deals are all for less than a month the APRs are very high. One admits charging 1355% but that is on the assumption that the repayment is four weeks away. It may be a lot less.

That particular company makes much of the fact that APRs are not really an adequate way of assessing a loan over a short period. In 2004 I did a Radio 4 programme on the cost of credit and interviewed Robin Ashton of Provident Financial. His PR man John Lamidey said to me that if I lent him £20 and a week later he gave it back to me and bought me half a pint of beer the APR would be 4197.7%. Which is true. Or was when beer was £3 a pint.

Provident is still making the claim that APRs are not the best way of working out the price of short term loans – especially those collected door to door. Responding to a recent controversy over Christmas vouchers which carry a 222% APR Provident spokesman David Stevenson said

Everybody knows that APR is not useful for comparing small loans that are repayable over a short period.

Daily Mail 28 October 2008

But why not? If that is what the arithmetic says, surely it shows that the truth is rather the opposite.

APRs are a good way of showing us with arithmetic that our instinctive feelings about their cost are simply wrong. Because for the company that makes them it is the arithmetic that counts. They have money lent out all the time. And in the £20 for a pint of beer example, to charge a reasonable 13.9% APR you would have to repay the £20 and hand over a 5p piece a week later. And it is this lack of arithmetical understanding that makes some people think a return on capital of 437.4% is quite modest rather than the usury it actually is.

It was outrage at some of these three and four figure APRs that led campaigners to call for a cap on interest rates when the Consumer Credit Bill was going through parliament. Caps already exist in a handful of European countries including Netherlands where there has been one since the 1940s, France, Italy, Poland – which recently introduced one – and Germany where rates are capped at twice the average interest rate charged, which fixes the cap currently at around 18%.

In the UK a cap of 18% would not only banish log book loans, payday loans and doorstep lenders like Provident. It would also stop almost all store cards, they typically charge more than 25%, it would end the rate charged on cash advances on just about every UK credit card – they are typically well over 25%. And it would also render unlawful the rate charged even on purchases by these twenty cards from well known banks.

No wonder the entire financial services industry in the UK opposed an interest rate cap when it was considered as part of the preparations for the Consumer Credit Act 2006.

Of course, that doesn’t stop others persisting with trying to get a cap. Jim Devine the Labour MP for Livingstone has put before Parliament his Interest Rates (Maximum Limit) Bill which would cap rates.

Although the Government rejected proposals to introduce a cap as the Consumer Credit Bill was going through Parliament the Minister at the time, Gerry Sutcliffe, did promise to review the situation if the new provisions didn’t work. They’re not. And it should.

In 2004 I did a programme on Radio 4 called The Price of Poverty about the cost of borrowing for low income families. And I looked at a cap on interest rates. And it was very interesting that in the UK the closer you got to grass roots – to people dealing with the real effects of loans – the greater was the desire for a cap. And the further away you got from real debt, from doorstep lenders, to academics and politicians and even consumer policy groups the less they wanted a cap.

Not the Regulators

So the banks are

not listening. The Government is not listening. And nor is the Regulator.

In the UK that generally means the Financial Services Authority – the FSA. Though just to confuse things the Office of Fair Trading also has its say on credit. And the Advertising Standards Authority still regulates some of the promotional material for some financial products.

The FSA’s guiding principle is that financial companies should promote their products in ways that are clear, fair and not misleading. And that they should treat their customers fairly.

You may ask of course what sort of multi billion pound industry is it that has to be told – to be regulated – to treat its customers fairly. And when that principle was first laid down its first question was ‘what do you mean by fairly?’

But in some ways that is a fair question. Because in my view the problem with FSA regulation is that it is about principles and process and not about products. But what harms customers? It is the products – not the principles and processes – that do people harm.

My FSA would work in a different way. If it saw dangerous products on sale it would tell the public at once. If a firm withdrew a product on safety the FSA would issue a press notice and tell people who made it and why it was withdrawn. It would have the power to seize some products and destroy them. It would be able to raid premises that were producing dangerous products and close them down. Ultimately it could prosecute the companies and their directors who made dangerous products.

The industry will say it would never work. It would stifle innovation, destroy competition. It would damage the reputation of financial services companies and weaken further any trust in their products. And worst of all it would remove customer choice and the freedom to decide what suited them.

But bear with me a minute. Let me take you to a parallel universe, to a place where the FSA does do all those things. Some examples from the last few weeks.

Tesco Stores Ltd has recalled a batch of its own-brand Strawberry Pencils confectionary product, due to a small piece of metal being found within one packet of the product.

Quaker Oats has recalled a batch of Quaker Oats Original and Quaker 'Jumbo' Rolled Oats due to the potential presence of confused flour beetle (Tribolium confusum) in the product.

Dairy Crest Ltd has recalled two batch codes of Country Life Spreadable due to the possible presence of pieces of rubber in the product.

Seymours of Norfolk Ltd has recalled all batches of infused olive oil products, due to the potential risk of botulism.

Wm Morrison Supermarkets plc has recalled its own brand Frozen Family Favourites Potato Croquettes due to potential contamination with pieces of soft blue plastic.

Source: Food Standards Agency www.food.gov.uk

Over the last couple of months Fray Bentos minced beef and onion pies, Primula Cheese Spread, Wild Bean Café Ham Cheese and Pickle Sandwiches, Morrisons Chicken Thins, Marks & Spencer mustard, Alrdred the Bakery luxury muffins, Waitrose organic eggs, Paxton’s chicken liver pate, Asda flapjack mini bites, Sainsbury’s chocolate and toffee crisp, Tesco houmous, Tesco spotted Dick sponge pudding all withdrawn on health or safety grounds.

Now this of course is the other FSA – the Food Standards Agency. And the parallel universe is one where our health is involved. And where customers are not given the choice to catch botulism, crunch a confused flour beetle or swallow small pieces of soft blue plastic.

After naming these products and companies and the dangerous – or potentially dangerous – products they have been selling, have customers fled from those products or companies to their rivals? No. Have people given up buying food and started to grow their own? Have people stopped eating altogether? No. Quite the opposite. Because we know that there is a Food Standards Agency – and strict food hygiene regulations – we buy food with great confidence that the sell by date is right, the ingredients accurately listed and that we won’t get botulism or crunch down on a confused flour beetle.

And that is why the motto of the FSA in this parallel universe is – safer food, better business.

Wouldn’t it be good if our FSA could change its motto to ‘Safer financial products, better business.’ Because if we knew the products we buy from the banks and building societies had their ingredients accurately and comprehensively listed, that they did what it said on the tin in big letters – not what it said on p.94 of the terms and conditions, and that they were safe then we would buy more not fewer of them.

We saw how that might help recently with Payment Protection Insurance PPI. When I used to talk about PPI and its high profit margins, its ubiquitous mis-selling, and the way it doubled the cost of borrowing pushing people further into debts they couldn’t afford I was challenged, vilified, shouted at, and dismissed as an ignorant journalist. Not any more of course. Consumer groups began to complain, the FSA investigated, and finally the Competition Commission has given us remedies.

The FSA’s approach to this problem in 2005 was to swing straight into action and – do some thematic work.

In 2005 that uncovered widespread mis-selling. The FSA published its general findings and promised more thematic work in 2006. A year later that showed nothing much had changed. So it leapt into action and promised to ‘engage with relevant trade associations’ and ‘examine the case for further regulation’. And of course plan another piece of thematic work. In 2007 there were still concerns about mis-selling. Again nothing was done. And worse throughout this three year period all the names of firms which had been caught mis-selling were kept secret so consumers were kept in the dark and the firms were free to carry on mis-selling. We know now that some of them did. Over those three years more than 19 million people potentially missold PPI.

Fortunately in a parallel universe the Office of Fair Trading and then the Competition Commission were also looking at PPI. And last week the Commission took a parallel universe line. It wasn’t going to mess around with process, with treating customers fairly, with thematic work and cosy chats with trade bodies. No. It would ban single premium sales of PPI. It would ban sales of any PPI at the point of sale of the loan – the provider would have to wait 14 days before it could market PPI. And if they did it would force them to show the true cost of the loan with and without PPI. And adverts would also be controlled.

The industry of course was very upset. Largely because these remedies would work. A ban will always do more than another round of thematic studies. And that is why food poisoning is very rare the UK. And financial mis-selling is, sadly, still very common.

Of course these remedies will not stop completely the mis-sale of PPI. I tend to think most PPI sales simply push people, who perhaps shouldn’t be borrowing money at all, further into debt. But I was given a different line last Tuesday at a dinner with financial advisers – or as they call themselves now wealth managers. An accountant, an auditor in fact, who had worked for several banks in his time said his view was very simple. When a bank lends you money it takes a risk that you won’t pay it back. Covering that risk is built into the price it charges you. In other words you are paying for the risk of not being able to pay it back in the interest rate. So why does it try to make you buy insurance to protect the risk that you are already paying for? And why do you pay the premiums when it gets the benefit?

But sadly insurers and brokers are using the recession and rise in redundancies to peddle PPI as a solution. Encouraging people to pay for insurance that (a) may not pay out at all if they bought it anticipating their own redundancy and (b) will normally pay for only 12 months when the job market is likely to mean that people who do become unemployed will stay out of work for a long time. So far from being an opportunity the looming recession and the growing toll of unemployment make this the worst time to take out PPI. And the worst time to sell it.

Rather they should be saying to people who are trying to borrow money – are you sure this is a good idea? With unemployment rising and the cost of borrowing in the real world going up the advice should be don’t borrow. Not borrow and spend extra money insuring the risk.

But sadly debt and borrowing is unadvised. It takes a lengthy fact find, tens of pages of documentation, and a cooling off period before someone is allowed to invest £20 a month into a pension plan. But you can borrow £10,000 or take out a credit card without any real assessment of your finances, your attitude to debt or your understanding of the consequences of a life change on whether you could repay it.

So what we need is a regulator that will have the power and the desire to ban dangerous products. To step in and stop their manufacture. And to make sure that it is as difficult to sell people debts as it is to sell them investment products.

So in future when this global credit crisis is long gone – and Alistair assure us the worst will be over by 2011 – the regulator then can stop 100% mortgages, self-certified loans, 437% APRs, Payment Protection Insurance that does not pay out, credit card cheques, store cards, extortionate charges for getting cash, and then at last we could say Safer Financial Products, Better Business.

Conclusion

Banks are not

listening. They are too big to fail so their mistakes are paid for. But their

customers are too small to care about so their identical mistakes – caused by

relying on the banks – are not paid for.

The Government is not listening. While controlling investment strictly it fails to control debt, leaving it to individual choice and refusing to cap usurious interest rates.

The regulator the FSA is not listening. It fails to control dodgy products. If even one person can benefit it won’t ban anything even though it could be regulating it out of existence.

So MALG has a lot to do in the next twenty years to make them listen.