This talk was given 20 November 2008

The text here may not be identical to the spoken text

BANKING CODE STANDARDS BOARD

ROAD SHOW 20 November 2008

THE FUTURE OF THE BANKING CODE

Most of you do compliance so you won’t be surprised if I start with my own initial disclosure statement. I am a freelance financial journalist. I do present Money Box on Radio 4. But I am not here as a representative of Money Box still less, God forbid, of the BBC.

I am sure I don’t need to tell an audience like this that there is a world of difference between being ‘Paul Lewis from Money Box’ or ‘BBC presenter Paul Lewis’ and being ‘Paul Lewis a financial journalist who presents Money Box’. It gives an arms length between me and the BBC. So it can have all the advantage of whatever little talent I have without the disadvantage of being responsible for me or my views.

Anyway thank you for asking me to speak to you today. I was asked to talk on ‘the media’s perspective’. I think ‘sceptical but glad it’s there’ perhaps sums up the media perspective. But today I want to give you my view of the Code and the changes that may well be ahead. And I have been writing about personal finance for even longer than the seventeen years the Code has been around.

I was asked recently what is the banking industry good at? And what is it bad at? And I replied that it is very good at doing precisely what it says in the small print. But very bad at doing what it seems to say in the big bold typeface in the promotional material. And I have to say that the Banking Code is a very good example for that analysis.

Before I come to that let me say that The Banking Code has introduced important improvements in the way banks treat their customers – can I save time by automatically including building societies when I say ‘banks’? For example the Code sets out the timetable for moving your account from one bank to another. It lays down the rules which make cash machines show clearly if there will be a charge for getting your own money out. It introduced summary boxes which set out briefly – well fairly briefly – brieflier anyway! – the terms and conditions of credit cards and from October extended them to savings accounts and unsecured loans. It contains the rules for letting us know about changes in terms and conditions. It ensures that the minimum repayment on a credit card is always more than the interest charged that month – there was a trick wasn’t it? It has made the banks promise that people with poor credit records have access to at least a basic bank account if an overdraft or cheque book is not suitable. And the banks have at last agreed to consider if people can repay their debts before they are lent more money. All those things – and there are more – are good. Though quite why it took the pressure of the Code to do them I’m not sure.

But from 1 November 2009 it seems inevitable that the Financial Services Authority will take over regulation of most of retail banking and 40% to 50% of the Banking Code will move from being voluntary to being statutory. But I believe that there will still be a need for something like the Code – though I hope it will be rather better – clearer, tougher – than the present one.

Let me give you one example of where the Code has got lost in this gap between the offer in the big bold typeface and the details in the small print.

Let’s start on page 6 with one of the key commitments set out in section 2.

Those eleven words seem clear to me. Whenever the interest rate changes on my account you will tell me.

And I am encouraged to believe that by page 8 where there is a whole section on interest rates. Para 4.4 says again

4.4 We will keep you informed about changes to the interest rates on your accounts

There it is again in 14 words. And again I think ‘that’s clear. When rates change my bank will tell me.’ And nowhere in the Code does it really say anything different.

But to find out what it means you have to turn to another document the Banking Code – Guidance for Subscribers. There the meaning of these dozen or so words is helpfully explained – and it takes 987 words to do it.

Here it is. And it turns out that keeping you informed can mean a notice in the branch or a small ad in two newspapers. If I have understood those 987 words correctly you will only be personally informed if

Now Bank Rate has recently fallen by 2 percentage points. So with the extra 0.25 points allowed by the Code banks can cut the rate on an account from say 5% to 2.75% without telling anyone. So if a customer has £10,000 in that account and are expecting to get £500 a year interest you can cut that to £275 without informing them. That’s a loss of £225, a cut of 45% in their income. But no personal notice.

There is another provision on interest rate cuts. This is in paragraph 4.8 of the Code

4.8 If you have a variable-rate savings account with £250 or more in it and the interest rate has fallen significantly compared with the Bank of England base rate, we will contact you within a reasonable period of time to:

Every word of this needs deconstructing. And the guidance helpfully tells us what ‘£250 or more’, ‘the interest rate’, ‘fallen significantly’, ‘compared with the Bank of England base rate’, ‘contact you’, and ‘reasonable period of time’ all means. Another 812 words and a table to explain it. But as far as I can see it sums up like this

That’s rather different from the previous rules. But it’s quite easy to remember isn’t it – 0.25 and £500, 0.5 and £250, not forgetting that the 0.25 is MORE THAN and the 0.5 is OR MORE. I don’t know why people are confused.

Now last November the Bank Rate was 5.75%. Twelve months on it is 3%. A fall of 2.75 percentage points. So if you were getting 5.99% on your money you can deduct the bank rate change bringing you down to 3.24% and then another 0.49% to sneak in below the ‘0.5% or more’ provision and you are being paid just 2.75%. And you will not be told! That’s a drop in income on £10,000 from £599 to £275 – a fall of £324 or 54% without admitting it!

And there is of course yet another exclusion to be trotted out when a customer complains they didn’t realise that you had cut the rate paid on their money.

You won’t find this anywhere in the Code of course. After all the Code is only 10,000 words long and you can’t fit all the fiddly bits in that few words can you? No. But in the 34,000 words of the Guidance at the bottom of page 19 it says this

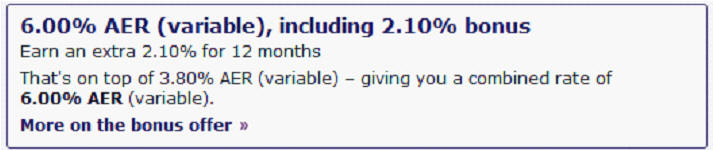

Bonuses offered for a fixed period of time, either to new or existing customers, should not be considered when deciding whether or not the interest rate on an account has ‘fallen significantly’ relative to the base rate.

Let me give you an example of what this means. The NatWest e-savings account pays 6% but that includes a bonus of 2.1% for twelve months. In other words at the end of a year that rate will fall to 3.8%. And yes I do know that 6.0 – 2.1 = 3.9 but as the website explains AER and gross rates mean that in this case 6 - 2.1 in fact = 3.8. Looking at the NatWest motto there, it’s clearly ‘another way’ of doing arithmetic. In any case the goto rate is 3.8%.

If you look at the moneysupermarket.com best buy tables for instant access savings with at least £500 so you are covered by the Code, 6% is the second best instant access savings account rate. There are six accounts offering 6% on your money and one offering 6.3%. So the NatWest offer is 7th down but is in fact 2nd equal. But what happens a year from now? The NatWest e-savings account falls from 6% to 3.8%. Where does that put it in the best buys?

We don’t know in a year but today we go down to the bottom of page 1 of the moneysupermarket list that takes us to 25th place Skipton BS paying 5.1%. The next page takes us down another 30 products down to 55th place Derbyshire BS paying 4.5%. Next page takes us down and there it is on p.3 another account paying 3.8% Direct Line direct access.

So a year from now the NatWest e-savings account will have plummeted from second in the best buys to 72nd. And if we have entrusted that High Street bank with £10,000 of our savings the return will have fallen from £600 in the first year to £380 in the second – a cut of £220 or 36.7% in our income.

But NatWest doesn’t have to tell its customers when that happens. According to the Code – or at least the Guidance to the Code – a fall of nearly 37% in the income you earn that does not count as the interest rate having ‘fallen significantly’. Now, of course, the Code does say – the Guidance again – that

Subscribers should ensure that the terms of any relevant bonus period are clearly communicated to customers prior to opening, and on opening, the account.

But it deliberately remains silent about the change at the moment it matters. Not in the euphoria of getting the second best savings rate on the market. But at the moment twelve months later when the cut falls and anyone with an ounce of sense would leave NatWest faster than Russell Brand left the BBC.

And it gets worse. Because if base rates fall another 1% over that twelve months as is widely expected NatWest can slowly reduce the rate by a total of 1.49% cutting the goto rate to 2.31% without telling their customers. That costs you £369 or 61.5% of your income.

And I know you are thinking where does that put the once 2nd best rate in the best buy tables for instant access £500 or more? It would be in 153rd place nestling between Bank of Scotland’s Halifax Premium Savings Direct at 2.42% - HBOS clearly means something by ‘premium’ that I don’t – and Cheshire BS’s 2.3% Easy Access. Worth noting that Cheshire doesn’t even pay that rate if you make more than four withdrawals in a year.

We can see by delving deep into the best – sorry now the worst buy tables – why the average rate paid is around 3% and the worst is less than 1%. We’ve got down to middle of second hot hundred accounts. But the list goes on…

Royal Bank of Scotland – now known by its initials HMG – offers a stunning 1.9% on its easy access account.

Nationwide Cash Builder is 1.55% - not sure how much cash you would build up in that. It’s in 197th place.

Dropping down to 264th place we find that old favourite Halifax Liquid Gold offering an astonishing 0.25% – easy access again no doubt to the £25 a year you would earn on £10,000.

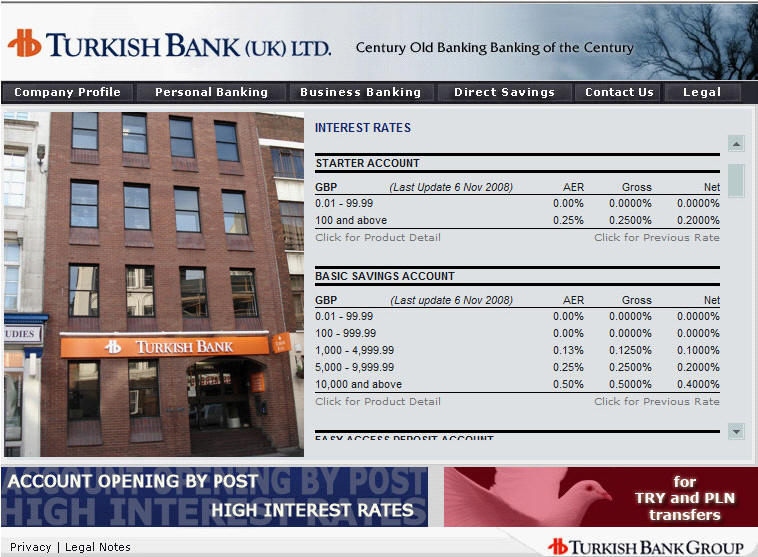

But bottom in 271st place is Turkish Bank Basic Savings Account it pays 0.00% and according to MoneySupermarket that rate is fixed and payable on maturity! Good to have that certainty! And well worth waiting for! From a member of the BCSB! And in case you don’t believe Moneysupermarket tables here is Turkish Bank’s website. And to be absolutely fair to Turkish Bank on £10,000 and above it does pay 0.5%.

Looking at these tiny rates it seems to me that under the Code quite a few could switch to negative interest rates after the recent cuts in Bank Rate without telling customers that had happened. And none of these ridiculous rates on savings nor their misleading names are dealt with by the Banking Code.

This version of the Code came into force in March 2008 following a review by Mike Young – formerly of the Bank of England. One of his recommendations was that banks should inform customers that a bonus rate was about to come to an end. He suggested that a month’s notice should be given. But the banks rejected that idea. And the reasons given to me on Money Box by not a banker but by Adrian Coles the Director General of the Building Societies Association was

the danger of "information overload. You can give [customers] too much information. And if you give them too much information, in fact it means they read nothing at all…

The judgement that the banks and building societies have made is that if that information is given both in product literature and at the point of opening the account…that would be sufficient to look after the customers’ interests." (Money Box, Radio 4 29 March 2008)Or maybe those of the building societies and banks.

So the banks and building societies tempt us in with good rates and then quietly cut them when they hope no-one is looking. And they don’t tell us they’ve done that entirely in accordance with the Banking Code.

There are many other examples of such get out clauses in the Code’s tens of thousands of words. A cynic might see Code as a document which sets out in great and meticulous detail not how to treat customers fairly but how to get away with misleading them.

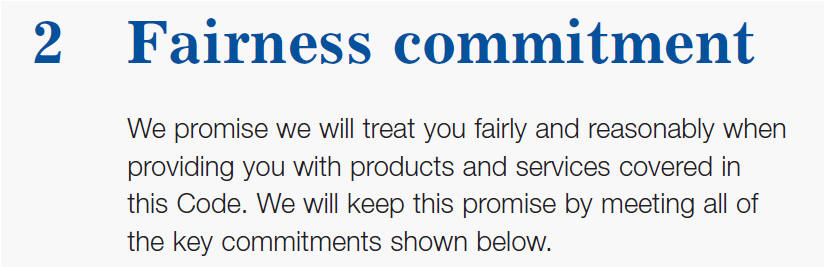

And talking of treating customers fairly – which you’ll have to do a lot more of from November 1st – there was much debate about Mike Young’s recommendation that there should be what was called at the time an overarching provision to treat customers fairly. Just in time for the Code’s launch on 31 March that was eventually implemented. Here it is

But then the industry proceeded with a very expensive legal challenge to exempt its controversial overdraft charges from a law which say they must be fair– or at least that they must not be unfair. So the banks want the courts to establish that overdraft charges do not have to be fair.

And I say ‘banks’ but Nationwide joined in too. Just after it changed its motto from ‘proud to be different’. Perhaps because it no longer was.

When the FSA takes over in November banks will have to treat their customers fairly not under a voluntary Code of Practice but under the legal rules set down by the FSA. And it will be a complex argument won’t it to say that they can do that without being subject to the Unfair Terms in Consumer Contracts Regulations 1999. Though I am sure there are lawyers working even now on explaining how banks can treat their customers fairly by putting terms in their contract which are unfair – or at least which are exempt from being judged to be fair or unfair.

Let’s look now at FSA regulation. At the heart of its regulatory regime is this principle of Treating Customers Fairly. The fact it is at the heart does raise the question doesn’t it of what sort of industry is it that has to be told by the regulator to treat customers fairly? And when it is told to do that often replies ‘what do you mean by fairly?’

That’s the problem with FSA regulation. It is about principles and process and not about products. But what harms customers? It is the products – not the principles and processes – that do people harm.

My FSA would work in a different way. If it saw dangerous products on sale it would tell the public at once. If a firm withdrew a product on safety the FSA would issue a press notice and tell people who made it and why it was withdrawn. It would have the power to seize some products and destroy them. It would be able to raid premises that were producing dangerous products and close them down. Ultimately it could prosecute the companies and their directors who made dangerous products.

I know what you’re thinking. It would never work. It would stifle innovation. It would destroy competition. It would damage the reputation of financial services companies. It would weaken further any remaining trust in their products. And worst of all it would remove customer choice and the freedom to decide what suited them.

But bear with me a minute. Let me take you to a parallel universe, to a place where the FSA does do all those things. Some examples from the last few weeks.

Friday 14 November

Netto Foodstores Ltd has recalled a batch of Starberg Shandy 8pk due to a fault

to the neck of the bottle leading to an increased risk of breakage.

Thursday 13 November

Dairy Crest Ltd has recalled two batch codes of Country Life Spreadable due to

the possible presence of pieces of rubber in the product.

Wednesday 12 November

Seymours of Norfolk Ltd has recalled all batches of infused olive oil products,

due to the potential risk of botulism.

Tuesday 4 November

Waitrose Ltd has recalled its own-brand Minced Beef and Onion Pie due to

incorrect date coding of the product.

Wednesday 8 October

Wm Morrison Supermarkets plc has recalled its own brand Frozen Family Favourites

Potato Croquettes due to potential contamination with pieces of soft blue

plastic.

Over the last couple of months Primula Cheese Spread, Wild Bean Café Ham, Cheese and Pickle Sandwiches, Morrisons Chicken Thins, Marks & Spencer mustard, Alrdred the Bakery luxury muffins, Waitrose organic eggs, Paxton’s chicken liver pate, Asda flapjack mini bites, Sainsbury’s chocolate and toffee crisp, Tesco houmous, Tesco spotted Dick sponge pudding have all been withdrawn on health or safety grounds.

Now this of course is the other FSA – the Food Standards Agency. And the parallel universe is one where our health is involved. And where customers do not get and do not want the choice to get botulism or eat small pieces of soft blue plastic.

All those products and companies have been named on the FSA website and the full details given of the dangerous – or potentially dangerous – products they have been selling. Has the reputational damage to those companies been so severe the FSA should have kept those details secret? No. Have customers fled from those products or companies to their rivals? No. Have people given up buying food and started to grow their own? Have people stopped eating altogether? No. Quite the opposite. Because we know that there is a Food Standards Agency – and strict food hygiene regulations – we buy food with great confidence that the sell by date is accurate, the ingredients accurately listed and that we won’t get botulism or swallow small pieces of soft blue plastic.

And that is why the motto of the FSA in this parallel universe is – ‘safer food, better business’. Wouldn’t it be good if our FSA could change its motto to ‘Safer financial products, better business.’ Because if we knew the products we buy from the banks and building societies had their ingredients accurately and comprehensively listed, that they did what it said on the tin in big letters – not what it said on p.94 of the terms and conditions, and that they were safe then we would buy more not fewer of them.

We saw how that might help in the recent – the almost five year long – saga of the dangers of Payment Protection Insurance or PPI. When I used to talk about PPI and its general inappropriateness, its high profit margins and its frequent if not universal mis-selling I was challenged, vilified, shouted at, and dismissed as an ignorant journalist. Not any more of course. Respectable consumer groups began the process, the FSA carried it on, the Office of Fair Trading got involved and finally the Competition Commission has given us remedies.

Let’s look first at the FSA’s approach. The FSA began to regulate general insurance in January 2005. And it got straight down to work on PPI – it did some thematic work.

2005: 30 PPI firms visited. All 30 posed a high overall risk to customers with a risk of inappropriate sales, inadequate supervision, poor quality advice, commission driven sales targets, training and competence insufficient and variable compliance monitoring.

It also did 52 mystery shopping tips – broadly consistent findings with many or most showing a risk of inappropriate sales, poor quality advice, lack of explanation of exclusions and only 1 out of 24 explained clearly how a single premium policy would be paid for by adding it to the loan.

So what did the FSA do to protect customers? It kept the names of the companies which were potentially mis-selling this product secret. It called for improvements. And it promised a second round of thematic work in 2006.

A year passed. Another 6.5 million people year were potentially missold this expensive and often useless product.

In 2006 the results of that thematic work were published. It reported three key areas of what it called ‘widespread concern’. Customers still not given clear information. Exclusions still not fully explained. And single premium policies not sold with the best interests of customers in mind.

The FSA leapt into action and promised to ‘engage with relevant trade associations’ and ‘examine the case for further regulation of PPI sales’.

Again all the names of these mis-selling firms were kept secret so they were free to carry on mis-selling. Another year, another 6.5 million people potentially missold PPI.

In 2007 there was a thematic update. Mystery Shopping Exercise Phase III produced very similar concerns to the previous two. Some slight improvements but fewer than half of the firms explained the exclusions, most did not explain if they were selling a single premium policy, and most customers were not told of cancellation rights.

Throughout this three year period all the names of firms which had been caught mis-selling were kept secret so they were free to carry on mis-selling. And a total of 19 million people potentially missold PPI.

Another year passes. Then on 7 October 2008 the FSA finally gets tough. Action was taken against Alliance & Leicester for mis-selling PPI. Over three years it had potentially missold PPI to 210,000 customers charging each of them £1265. It was fined £7 million. But hang on a minute. 210,000 times £1265 is £265,650,000. So the fine is less than 3% of turnover. The profit margin on PPI could be – well you kow better than me but let’s say a conservative 40% – so A&L made more than £100 million profit. And the fine is less that 7% of that. It’s an overhead not a deterrent.

Fortunately in a parallel universe the Office of Fair Trading and then the Competition Commission were also looking at PPI. They took their time too. But last week the Commission took a parallel universe line. It wasn’t going to mess around with process, with treating customers fairly, with thematic work and cosy chats with trade bodies. No. It would ban single premium sales of PPI. It would ban sales of any PPI at the point of sale of the loan – the provider would have to wait 14 days before it could market PPI. And if they did it would force them to show the true cost of the loan with and without PPI. And adverts would also be controlled.

The industry of course was very upset. Largely because these remedies would work. A ban will always do more than another round of thematic studies. And that is why food poisoning is very rare the UK. And financial mis-selling is, sadly, still very common. And PPI is still missold despite paragraph 8.6 of the Code and two paragraphs of explanation in the Guidance.

So when the banking industry is regulated by the FSA that is to me a golden opportunity for it to make its peace with a suspicious public. And to do that through a new code in parallel to FSA regulation. And when the new Code says

it will mean just that.

And not be accompanied by 3500 words in separate guidance which explain not what you will tell us but what you can get away with not telling us.

Thank you.