This talk was given 16 October 2008

The text here may not be identical to the spoken text

Building Societies Association Annual Lecture

London Stock Exchange 16 October 2008

Beat the Banks

As John Goodfellow kindly said I’m Paul Lewis a freelance financial journalist, although best known I guess for my work presenting Money Box on Radio 4. But I am not here representing Money Box or, god forbid, the BBC. I am here as myself and the opinions and comments I make are mine alone.

I’m calling today’s lecture ‘Beat the Banks’. The title was in my mind because I had just been discussing an update to this book – on which incidentally I earn no royalties, it’s published by Age Concern so if you buy one the charity gets the money not me – which I called Beat the Banks.

And before you all feel smug, I have to tell you this was a small volume. And in fact I would have called it ‘Beat the Banks and Building Societies’ but there wasn’t room. Because it’s partly about avoiding the tricks that banks – and building societies – play on us to take money off us. And in many areas there isn’t really that much difference between banks and building societies.

Today I want to talk to you about making that difference. About how mutuals can beat the banks. But I have scrapped large parts of that lecture. Because I cannot really stand up in front of an audience now without talking about the world banking crisis. Every day when I have sat down to carry on writing this lecture I have had to go back to the beginning as banks crashed or were nationalised or both and I had to rewrite the start.

Governments have stepped in with yet more eye watering sums of money. And stock markets have illustrated the old saying that share prices can go down as well as plummet.

Over the last month I did wonder if I would have to rename it ‘Beat the Bank’! Because it has been a week by week Wall Street game show called Last Bank Standing.

It started with a double act – the comedy twins Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac. No-one had heard of them but on Sunday 7th September we were told they had disappeared into Federal Reserve.

The next Sunday 14th September Lehman Brothers went bust and then Merrill Lynch was rescued.

Since then every Sunday a crisis has removed another player – sometimes several. The game became so popular that midweek episodes began. It crossed the Atlantic to the UK and then Europe. Two Sundays ago the song and dance duo Bradford & Bingley collapsed. Then in Europe Dexia was rescued. And after the next weekend’s crisis talks first Landsbanki and then Kaupthing fell. And then this weekend of course the Government effectively nationalised Royal Bank of Scotland and took a 40% stake and two board places in HBOS.

And then as I was putting what I might grandly call the finishing touches to it the US government decided that $700 billion was nothing like enough and committed another $250 billion to taking stakes in eight of its remaining banks. And just this morning we heard that the Swiss Government had put $30 billion to buy the duff assets of UBS.

Since I invented the game in my weekly column on the Saga website more than thirty banks and the like have failed, been rescued or nationalised. And some of those early players who went out just seem like distant memories don’t they? Wachovia? Washington Mutual? Fortis?

I speculated initially that Last Bank Standing may eventually be Federal Reserve. And it just about is after taking shares in eight banks. And here in the UK it seem as if The Treasury is going to be not just the bank of last resort but the bank of only resort.

But we shouldn’t be surprised. This is just fulfilling a Labour Election Manifesto pledge. When Gordon Brown became Prime Minister last year early thoughts that he might make Labour a more radical Government – perhaps even scrap the word ‘new’ in front of it – did not last long. He seemed just like Tony Blair without the charisma and the annoying wife. Or as Labour peer Lord Desai said in April this year “Gordon Brown was put on Earth to remind people how good Tony Blair was”. Lord Desai of course a leading economist. But now that joke seems a bit tired doesn’t it? It should be rewritten – Alistair Darling was put on earth to make us realise how good a chancellor Gordon Brown is – sorry, was.

We shouldn’t be surprised though. Last week Brown finally showed he was still a radical when he fulfilled this Labour Manifesto pledge.

We will…

· Exercise, through the Bank of England, much closer direct control over bank lending. Agreed development plans will be concluded with the banks and other financial institutions…

We expect the major clearing banks to co-operate fully with us on these reforms in the national interest. However, should they fail to do so, we shall stand ready to take one or more of them into public ownership. This will not in any way affect the integrity of customers' deposits.

Not of course from the 2005 Manifesto, still less from the 2001 or 1997 manifestos. No. This was from the document dubbed at the time the longest suicide note in history the Labour Manifesto of 1983.

So when a week ago Gordon Brown the Prime Minister and the Chancellor of the Exchequer Alistair Darling told us that they would provide both the capital and the liquidity the banks needed in exchange for shares no-one should have been surprised. Nor when the Prime Minister announced the internationally coordinated half percentage point rate cut by the fully independent Bank of England. Nor when the banks – which had been very happy to do the deal over the weekend because the alternative was so much worse – then said they wanted to keep all the money but not fulfil the promises they had made about dividends we shouldn’t have been surprised either. Because they were bankers weren’t they?

And I’ve done it again haven’t I? I said ‘they would provide both the capital and the liquidity the banks needed’ – I meant of course the banks and building societies. Because in that list – here it is again – of banks that have already disappeared in the game of Last Bank Standing we have to include a couple of building societies. This is a chronological list but really they should be later because it is mainly a list of when things happened not when they were announced and the move is being rubber stamped next week.

And the game is not over yet. Henry Paulson – Hank to his friends or actually I think to his enemies – warned that the half point cut and the £2.1 trillion spent on trying to bring the game to an end “One thing we must recognise: even with the new Treasury authorities, some financial institutions will fail,”.

So we are not quite at Last Bank Standing. And some of the competitors who remain are immensely strong. Citigroup, Santander, HSBC. I’d put my money in them. But then I put my money in Icesave so what do I know?

So we’re not quite at renaming this talk Beat the Bank. The remaining banks are bigger tougher, more dominant than they were before – and now guaranteed by the Treasury here, the Federal Reserve in the USA and by central banks across Europe. And I don’t think even a real mutual enthusiast could expect the Tipton & Coseley Building Society to take on The Treasury. But I suppose I could call the lecture ‘Beat the Banks While They’re Down.’

Don’t join them

It has become clear in the last few months that the way to beat the banks is not

to join them. Between 1989 and 2000 ten building societies decided to move to

the dark side and become banks. Abbey National began the move in July 1989. Then

Alliance & Leicester, Halifax, Woolwich, Northern Rock, all persuaded their

members to vote for demutualization and the members of Bradford & Bingley forced

the Board to vote for it and six new banks joined the half dozen old ones on the

High Street.

|

Society |

Converted |

Bought |

Years |

Owned by |

||

|

Abbey National |

12 Jul 1989 |

12 Nov 2004 |

15.34 |

Santander |

||

|

Alliance & Leicester |

21 Apr 1997 |

10 Oct 2008 |

11.47 |

Santander |

||

|

Halifax |

3 Jun 1997 |

10 Sep 2001 |

4.27 |

Halifax Bank of Scotland |

||

|

Woolwich |

7 Jul 1997 |

4 Oct 2000 |

3.24 |

Barclays |

||

|

Northern Rock |

1 Oct 1997 |

22 Feb 2008 |

10.39 |

Government |

||

|

Bradford & Bingley |

4 Dec 2000 |

29 Sep 2008 |

7.82 |

Government/Santander |

||

|

Average |

8.76 |

years |

||||

Of those who converted Woolwich only made it alone for 3¼ years before being bought up by Barclays. A year later Halifax was snapped up by Bank of Scotland – or was it a merger? And in 2004 Abbey was bought by the Spanish bank Santander. Then this year the last three survivors disappeared. Northern Rock nationalised in February. Bradford & Bingley nationalised in September. When the demutualization experiment ended last week as Alliance & Leicester finally migrated to the Costa Santander the average time for these six mutuals to survive as independent banks was just eight and three quarter years – even the longest only survived just over fifteen.

Meanwhile, four societies sold themselves directly into the arms of the shareholder world. Cheltenham & Gloucester took Lloyds’ shilling; National & Provincial joined Abbey; Bristol & West moved further west to Bank of Ireland and Birmingham Midshires moved north to Halifax – then already a bank.

|

Society |

Bought |

By |

Now owned by |

|||

|

Cheltenham & Gloucester |

1 Aug 1995 |

Lloyds |

Lloyds TSB |

|||

|

National & Provincial |

5 Aug 1996 |

Abbey |

Santander |

|||

|

Bristol & West |

28 Jul 1997 |

Bank of Ireland |

Bank of Ireland - branches to Britannia 2005 |

|||

|

Birmingham Midshires |

19 Apr 1999 |

Halifax |

Halifax Bank of Scotland |

|||

So every single one of those building societies that took the banks’ shilling is now gone as an independent company. Sold, rescued, or nationalised. Every one of them found that to be in the bottom half of the top ten was not a viable position. And that rapid growth was not possible without taking the risks that ultimately brought them all down. What a waste.

Now I have to say that although I always work meticulously when I’m on air within the BBC guidelines of impartiality I was one of the few journalists who remained completely sceptical about the advantages of demutualisation.

What possible benefits could it bring? Separating the people you sold to from the people who took the profits? It can only lead to the exploitation of customers.

And that view was supported in March 2006 when a parliamentary group produced a report ‘Windfalls or shortfalls? The true cost of demutualisation’. The group itself was pro-mutual – as I pointed out to them at the time. But the research was objective and done by Nottingham Business School and the author, Ian Welch, was a member of Association of Chartered and Certificated Accountants.

It found in summary that mutuals

· Performed better on financial performance indicators

· Offered customers better rates

It also found that when societies demutualised there was

· A substantial increase in directors’ remuneration

· No corresponding increase in performance

And that after demutualisations

· Consumer choice was restricted

· Higher charges outweighed the benefits of the windfalls for ex-members who remained customers

And that is especially true for shareholders of Northern Rock and Bradford & Bingley whose windfall is probably worth nothing.

And the people who are suffering from this are not so much the windfall shareholders – the members who sold their rights – they are the staff. In Northern Rock staff were encouraged to join the Save As You Earn scheme and in the annual report on 2007 there were around 6.5 million Northern Rock shares in it. I have spoken to employees who had several thousand pounds tied up in shares in their employer. And when I asked why, why go against all the advice on diversification and asset allocation and put your savings in shares in just a single company, one employee said to me ‘a bank’s not going to go bust is it?’

Competition

Now some will say

that competition kept prices down, broadened the range of products, led to

cheaper mortgages and easier lending. Indeed it did. And some people might still

tell you that was a good thing!

100% mortgages (many lenders). Excellent. 95% mortgage topped up with a 25% unsecured loan (Northern Rock)? Self-certification with few checks? (Bradford & Bingley). And of course Buy to Let – a business that depended on two things – easy credit and rising house prices. Couldn’t fail could it?

Two and a half years ago I started complaining about the number of mortgage deals on offer. About eighteen months ago I spoke to your Association and I did a familiar party piece showing how the number of mortgages had reached a new high. Then it was 10,655. A number which had grown by more than 4000 in a year as competition and innovation led to more and more ridiculous offers. In fact the number peaked in July 2007 at almost 12,000. How, I used to say, can any human being choose between 11,951 different mortgages? It is not possible. And if you cannot choose rationally then it is no choice at all. In fact it is not choice. It is confusion. Deliberate confusion so that people make mistakes.

Source: MoneyFacts July 2008

But once the credit crunch started the number fell back. And on 10 October last week was just 3281 residential mortgages. Now 3281 is still a lot to take in. But it is progress. And if we just take standard residential mortgages the position is better.

Source: MoneyFacts October 2008

That peaked at 4046 last September and is currently today 1676.

The credit crunch

I used the phrase

‘credit crunch’ there for the first time. And I have saved it deliberately.

Because those graphs illustrate the credit crunch. To see why we have to go back

to its origins.

One of my colleagues hates the phrase. She sees it as meaningless journalistic shorthand. Though why she hates it I’m not quite sure! So I decided to find out where it came from.

Source: Factiva October 2008

This graph shows the use of the phrase in UK newspapers every month back to the start of 2007. And you can see that at the start of 2007 it was hardly used at all – a handful of mentions. But then in August and September last year it took off. That continued into 2008 and in the first six months of this year it was used in UK papers no fewer than 21,093 times. Today it is used more than 3000 times every month – 100 times a day. The October figure based on just half a month.

So my colleague is right. It is a cliché used – probably overused – by journalists. It is in every story often in the headline.

Fancy a credit crunch mini-break? Try Iraq - The Guardian 9 October

Shoplift? Go naked? Don't wash? Observer Woman's thrift guide on how to survive the credit crunch in style (Observer 5 October)

In fact it has been used occasionally over the decades and the first use of ‘credit crunch’ in UK newspapers was in The Times on 7 June 1967. It referred to “the great credit crunch of last summer”. (The Times 7 June 1967 p24c) And again in October it referred to “the credit crunch of last year” (The Times 19 October 1967 p21e).

They were both referring to the credit crunch of 1966. And it was in fact that year when the phrase was coined by two economists, Sidney Homer and Henry Kaufman, who worked for the New York investment bank Salomon Brothers which collapsed in the 1990s during an earlier round of dealings in complex financial products. They wanted to describe the tight credit conditions in the Summer and Autumn of that year. And just read what led to it.

“It was preceded by a prolonged period of strong loan demand and easy credit conditions. From 1962 through 1965, sales of negotiable certificates of deposit – a financial innovation of the time – grew rapidly. The sales funded bank lending, which grew at annual rates exceeding 10 percent” (Owens and Schreft ‘Identifying credit crunches’ Contemporary Economic Policy April 1995)

Sounds familiar? Far from being journalistic claptrap ‘credit crunch’ does have a precise meaning among economists. It is a ‘period of sharply increased non-price credit rationing’. (Owens and Schreft ‘Identifying credit crunches’ Working Paper 92 1 March 1992)

In other words credit isn’t just expensive, the rationing is not done by raising the price. Rather, you can’t borrow money at any price. And it starts ‘sharply’ so there’s little time to prepare.

Source: MoneyFacts July 2008

And there it was in that graph of mortgages. A sharp decline in the products available. A credit crunch indeed.

American dreams

Where did it come

from? I’m going to remind you of that because it has an important lesson for

financial services.

Its origins are usually blamed on aggressive sales people in the USA selling mortgages to people with no deposit and no documents to prove their income. They didn’t care if the borrower could afford the loan, once a sale was made they got their commission. So it partly began with the commission driven sales – the very thing that has led to every major financial mis-selling scandal in the UK from pensions to payment protection insurance. So without commission driven selling we may not have had the crisis we have now.

But commission driven sales are only bad if the commission encourages mis-selling. That means the product is bad or at least can be bad for some people. And these loans were bad.

The USA is a big country. There’s lots of space to build new houses. And housebuilders wanted to expand. But with home ownership at a record high of almost 70% there were too few people able to buy more homes. At the time US house prices were rising strongly, as they were here. And so the clever people in the banks thought why not use that to sell more homes?

Welcome to the hybrid mortgage. A low fixed rate for a couple of years – the ‘teaser rate’ maybe as low as 1%. After that it reverted to a variable rate which normally floated as a percentage above Libor or the base rate which back in the post 9/11 word was fairly low. With a 1% fixed rate on an interest only mortgage more people could afford a home. So happy sales staff and happy customers. Even if they understood that their repayments might go from 1% to 2% or 3% they saw that as a rise of 1% or 2% not a doubling or trebling of the repayment. As I often say banks make more money than us because their better at arithmetic. Maybe not at higher maths but certainly at arithmetic.

And happy banks. House prices were rising strongly so even with the costs of foreclosure and a distress sale at auction the money lent was safe. Cynical but in bottom line banking it was a good deal. The whole system was predicated on rising house prices. And what made house prices rise? Demand. And what kept demand growing easy credit. And what kept credit easy? Rising house prices. Mmmmm.

It was so good that the lenders wanted to make everyone even happier by lending more and more. They needed to recycle the money that was coming in from mortgages to lend it out again. So they securitised the loans. Turning an income stream into capital and then using that capital to generate another income stream. And so on.

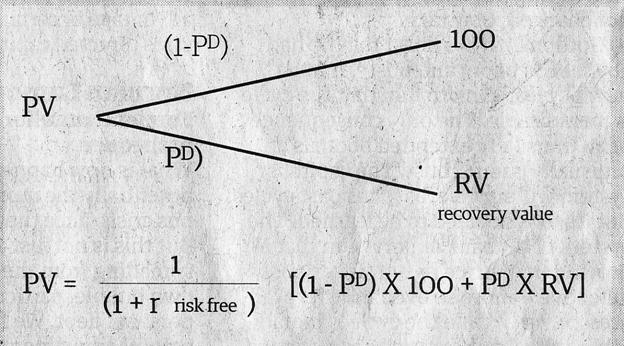

Now I’m not going to go into securitisation. But read this slide when you get bored with me.

And take it from me all the complex maths involved in securitisation, and credit derivatives and collateralised debt obligations, only works if you lie about the risk. Now mathematicians can tell you that you can separate the risk from the loan and even sell them separately to different people. But think about it. You have subprime loans – risky loans producing a higher stream of income but worth less. You sell them as safe loans producing less income but worth more and pocket the difference. And not only pocket it yourself. You create a big enough difference to keep the middle-men in work too – arrangers, depositors, asset managers, maybe guarantors, perhaps trustees, all well paid.

Now if you’re dealing in billions or nowadays even in trillions (when Lehman brothers went bust the administrator of the London office said it had £30bn passing through its doors every day – that is £1 trillion a year and that’s just the London office of one middle sized investment bank) and with that throughput then a small fraction of one percent can create a very nice income for these middle men and women. But to generate all that money at the heart of this process someone – perhaps everybody – has to be misled about the risk.

Alchemy

It’s financial alchemy – here’s one of the formulae – turning base loans into gold. It’s like solving global warming by inventing a perpetual motion machine. It would work – but it can’t.

That formula is from J P Morgan which largely invented these things and I was shocked yesterday as I sat on the tube and glanced at the man next to me and saw on his lap a report by J P Morgan Chase called ‘Credit Derivatives’ and dated that day 15 October 2008. I said to him ‘aren’t those the things that have caused all this trouble’ and he just smiled and said ‘yeah’ and got off at the next stop. Perhaps they are still selling them.

Another thought – which an economist I spoke to at the weekend said frightened her – is that it is a Ponzi scheme. Which promises high returns maybe 10% a month which are in fact paid not from any genuine return on the capital used but from the growing pool of new investors. At some stage it has to collapse. The trick for the fraudster is to get out with the money before it does.

For a while everyone was fooled. Even – perhaps especially – the referees. The ratings agencies who helped the process along by independently assessing the risk of organisations, of funds, of large chunks of debt. Early in July Moody’s – one of the main ratings agencies – sacked one of its senior staff and disciplined others for getting the credit ratings wrong on $1 billion of complex debt securities. They were actually Constant Proportion Debt Obligations – don’t even ask – and a computer programme which assigned them a risk factor was wrong. Moody’s discovered it in 2007 but kept quiet until it could quietly downgrade the securities when others were falling in 2008. A bit like hiding a body by throwing it out of the window during an earthquake.

So with middle men and women making a fortune, the banks shuffling off their risk, and sales staff earning good commission the whole machine turned on for five years. But slowly it creaked, groaned, and then began to come to a stop.

Reckless disregard for the

truth

The real reason

why the banks have stopped lending to each other, the real reason why the whole

banking system has collapsed, is because the banks don’t trust each other. And

they don’t trust each other because they have been lied to about risk. And they

know they have been lied to because they’ve been lying themselves.

Now I’ve got into trouble for using the word lying about this. And people have said it might be misleading, it might be misunderstanding. But is there any proof they were lying – that is they told an untruth and knew it was untrue. Well, maybe not. But they described the risk of these collateral debts with a reckless disregard for the truth. Which to me seems as bad. But whether they were liars or too dim or too careless to understand perhaps they should not have been in charge of all the money in the world for so long.

Yesterday at a lunch in Edinburgh the Chief Executive of the FSA Hector Sants admitted the FSA had not done very well over the banking crisis and went on to say “Many people forgot the golden rule: do not sell or buy things you do not understand.”

But this mistrust is why the most important part of the £500 billion the UK government promised last week was not the £50 billion to boost capital – top up the reservoir – in exchange for shares. Not the doubling to £200 billion the amount it would lend to banks to keep the system flowing. No. It was the £250 billion set aside to guarantee their loans. In other words if a bank did borrow money for 30 days or overnight because it needed the cash and when payback time came the bank was either bankrupt – or would be if it paid everyone – or the collateral it offered was not what it said on the label then the UK government, British taxpayers, would pick up the bill. In other words don’t worry if the bank lies to you, we’ll stand behind what they say.

It’s a bit like self-certification mortgages with a government guarantee so that if the borrower says they earn £100,000 a year and it turns out they’re fibbing don’t worry the Government will pay the mortgage.

European governments are so impressed with what we have done they have followed it. And so has the USA. And it is the cleverest solution precisely because it lets the banks carry on lying and the taxpayer picking up the bill. And that’s what worries me about it. It doesn’t reform the system that has gone wrong, it embeds it.

£500 billion in the UK. €1.5 trillion from European countries so far. $800 billion from the US government – though probably mainly spent on the wrong thing. More than £2 trillion pounds – and counting. This is bank robbery on a colossal scale. It will impoverish the world for a generation. And it was caused by the banks.

And so far it hasn’t worked. Here is the rate the banks lend to each other over three months with bank rate below and at the bottom a bar chart of the difference between them. Half point rate cut. No effect. The gap between Libor and bank rate simply widened. £2.1 trillion pounds to prop up the banks. Barely any effect. Shading down but still 1.71% above base rate.

Source: British Banker’s Association 15 October 2008

New regulation needed

Now many people

have said over the last few weeks that the time for apportioning blame – on

banks, on regulators, on credit rating agencies – is the future. After all if

the building is on fire first you put out the flames. One you’ve done that you

change the fire regulations and look for the arsonist. It sounds reasonable. But

you also call the fire brigade to put out a fire. You don’t invite the arsonists

round to Downing Street and ask them how to deal with the blaze.

But I am sure when blame is cast eventually in some official way rather than attention will turn to the FSA.

Which stands of course for the financial regulator the Fundamentally Secretive Administration.

I call it that because of its approach to naming names. The FSA polices adverts for financial products – it has a whole division whose job is to watch afternoon television, read the back pages of tabloid newspapers, and drive round looking at posters. In 2007/08 it considered more than 3000 adverts, promotions and complaints about them. More than 100 mortgage brokers had to withdraw adverts. And it found that 25% of websites investigated fell short of the proper standards. Which ones? It’s a secret. And such a secret that when I asked for them under the Freedom of Information Act 2000 I was refused and when I asked for a review of that decision I was refused again. The case is now with the Information Commissioner and no doubt in a couple of years will go to the Information tribunal and maybe the courts.

Despite that experience I do wonder whether, after the FSA’s light touch regime has clearly failed to stop the biggest banking crisis ever to strike the world that it should be given a new remit – to police products not firms, not process – not treating customers fairly. And incidentally, what kind of an industry is it that has to be told to treat customers fairly – and when it is asks what that means? Should the FSA stop the industry selling dangerous products. Not just products that are dangerous to the individual. But ones that are dangerous to the financial world.

And the FSA’s namesake the Food Standards does just that. It bans products. It names and shames them in the press. And its motto says it all – safer food, better business. Wouldn’t it be good if the FSA could change its motto to ‘Safer financial products, better business.’

Let me remind you of that quote from Hector Sants yesterday in Edinburgh. “Many people forgot the golden rule: do not sell or buy things you do not understand.”

Don’t let Alliance & Leicester carry on for three years misselling payment protection insurance to 210,000 people cost each of them £1265 and then fine A&L £7mn. On sales of £265 million that is just an overhead. Ban the product.

Don’t fine just two firms for selling geared traded endowment policies – ‘complex investments’ as the FSA calls them which the firms and their advisers did not understand – never mind the poor customers. Ban the products. They’re dangerous. But no. The FSA begins “a targeted programme of work examining the advice and sales processes” used in selling these products.

How much more would we buy if we knew that what we bought was safe? And the way it was sold was honest. Now I guess most of you don’t sell geared traded endowment policies. But I know a lot of you sell PPI. You could stop that tomorrow. You know it’s rubbish. You know that at a time like this anyone who has a thought they might be made redundant will want to buy it but may not be paid out for that very reason. And you know it is far too expensive. So if the FSA won’t ban it. The BSA could.

Simple honest products

I’m going to

finish with a final example of how the mortgage industry could reform itself.

And I know you will say that if we – the building societies – do this by

ourselves we will not be able to compete. I’ll come to the answer to that at the

end.

I’m talking about what you misleadingly call arrangement fees. Which they are not.

Source: MoneyFacts October 2008

They have soared over the last few years. For example, the average fee on a two year fixed rate mortgage has risen from £98 in 1992 to £1149 in October 2008 – eleven times as high. Have your costs risen elevenfold? Is what the plcs say about building society inefficiency true? Of course not.

But before I come to that let me return to the question of complex offers. I said earlier that it was generally good news that the number of mortgages had fallen to just over 3000. But that is still too many for a human mind to comprehend.

But a lot of that fall has been the complete disappearance of some lenders. And among the biggest remaining the number and complexity of offers is beyond human comprehension. Halifax is offering 173 mortgages in the latest edition of Moneyfacts. I wonder if the two Government appointed board members will have anything to say about that. And some building societies make very easy to understand single offers. One mortgage. Take it or leave it. But biggest – as in everything – is Nationwide which has 52 different offers. Between all 59 building societies there are 608 ordinary residential mortgage products – almost half the Moneyfacts total.

Is that sensible? Is that choice? Or is it confusion? How do you choose between Nationwide’s 14 different trackers? And 38 different fixes? It is what I have called before complexification.

complexification

But let me come to what that arrangement fee is. Nationwide has two fees £1499 and £599.

75% LTV Five year fix 5.78% +

£1499 fee

75% LTV Five year fix 5.88% + £599 fee

So the extra 0.1% is reflected in a £900 reduction in the fee. But which is best? And is it best to add the fee to the loan – and here’s a strange thing. The LTV is before the fee is added. So having said we can only lend you up to 75% of the value of your home it is in fact 75% plus whatever our fee is. Because we’re happy to add that on.

So which is better?

|

Bigger fee |

Smaller fee |

Small-Big |

Cheaper |

||

|

£1,499 |

£599 |

||||

|

Rate |

5.78% |

5.88% |

|||

|

ADD FEE |

Interest loan |

£57,800 |

£58,800 |

£1,000 |

Bigger fee |

|

Interest fee |

£433 |

£176 |

-£257 |

Smaller fee |

|

|

5 yr cost |

£58,233 |

£58,976 |

£743 |

Bigger fee |

|

|

PAY FEE |

£57,800 |

£58,800 |

£1,000 |

Bigger fee |

|

|

£1,499 |

£599 |

-£900 |

Smaller fee |

||

|

5 yr cost |

£59,299 |

£59,399 |

£100 |

Bigger fee |

|

|

Interest lost |

£167 |

£67 |

-£100 |

Smaller fee |

|

|

£59,466 |

£59,466 |

£0 |

No difference |

On a £200,000 loan on an interest only basis over those five years you end up paying £743 less interest. But you end up owing more money. What if you pay it off upfront? Then you still end up £100 better off. But what about the cost of that fee to you? If you borrow it on a credit card then you will be paying a lot for that money. So better to add it to the loan. But if you just take it out of your savings you may lose perhaps 5% a year. So paying it off upfront costs you a few hundred pounds and the smaller fee is cheaper. It only breaks even when the interest earned on the money lost is 2.22%. Perhaps you’ve put your money in a Nationwide cashbuilder card which pays a rubbish rate around that level. And of course all these figures will be different depending on the total loan. And of course different again over two years, three years, ten years.

But this is all simple spreadsheet stuff. Then there’s net present value….oh dear. Let’s stop there. It is clear that no-one sitting in front of you at a mortgage discussion can do the arithmetic and make a rational choice. Because ultimately the choices are the same. It is interest in advance. It would be more honest to call it that. And much more honest to scrap it and reflect that rate in the interest rate. Because a choice that cannot be rationally made is not a choice you should offer at all. And that would reduce the choices on Nationwide mortgages from 52 to around 30.

So what is the answer to the fact that if you do scrap the fee and add it to the interest rate you won’t top the best buy tables?

The answer is – now is your moment. No-one trusts the banks – the banks don’t even trust each other. No-one trusts the complexity and the difficulty of financial services. So start selling plain simple products. No fees. No tricks. No complexity.

Sell your mortgages as ‘no interest in advance’. And make it clear that the banks are playing the trick of reducing the headline rate by charging an upfront fee which is added to your debt.

Conclusion

Building societies

– you have a unique chance to distinguish yourself and differentiate yourselves

from the banks. You can do that by selling simple, honest, easy to understand

products with no tricks or strings attached. A return to what one of my

interviewees called ‘Quaker banking’. No-one quite knew precisely what that

was. But we did know precisely what he meant.

If there was ever a moment when you could ‘Beat the Banks’ this is it.

Thank you.

Words and images © Paul Lewis 2008. Free for non-commercial use as long as source is cited and this copyright notice attached.