This talk was given 18 October Month 2007

The text here may not be identical to the spoken text

Social Fund Annual Report presentation 18 October 2007

Banks, debt and low incomes

I’ve only been a journalist for twenty one years full time. Before that I was in what we called then the poverty lobby. Campaigning about the lack of income for pensioners and one-parent families. When I first got involved in that area of work I used to have a very simple view. People were poor because they lacked money. So to solve poverty you gave them money. And you took it from people who had enough money. And the fairest way to do that was through income tax.

Income tax was the great invention of the eighteenth century. A tax that seemed fair and was easy to collect. But today increasing income tax, openly anyway, is not a policy any politician puts forward – at least not if they want to get elected. And that has led to the introduction or raising of a whole host of less obvious taxes – Inheritance Tax, Climate Change Levy, Air Passenger Duty, Stamp Duty Land Tax – which now bring in a lot of money and help keep income tax down. Between them they are the equivalent of about 4p on the basic rate of tax.

And if you want to get more from income tax you have to do it quietly. One of the bigger hidden tax rises of the past ten years has been the almost doubling of the number of people who pay tax at the higher rate – from 2.1 million in 1996/97 to 3.9 million in 2007/08 – they pay 40% tax on some of their income instead of the basic rate which is currently 22%. A process known as fiscal drag as income rise faster than tax allowances.

Now as part of the Gordon Brown legacy to the future he announced in his last Budget in March that from April next year income tax would be cut. The basic rate would fall from 22% to 20%.

What the ex-Chancellor forgot to say was that for many low income families that represented a rise in tax. The starting rate of 10% - payable this year on the first £2,230 of income above the personal allowance of £5225 would be scrapped – simplified was the word used. What that means is that the starting rate of tax will now be doubled from 10% to 20%. And for some low income families that will have a devastating effect.

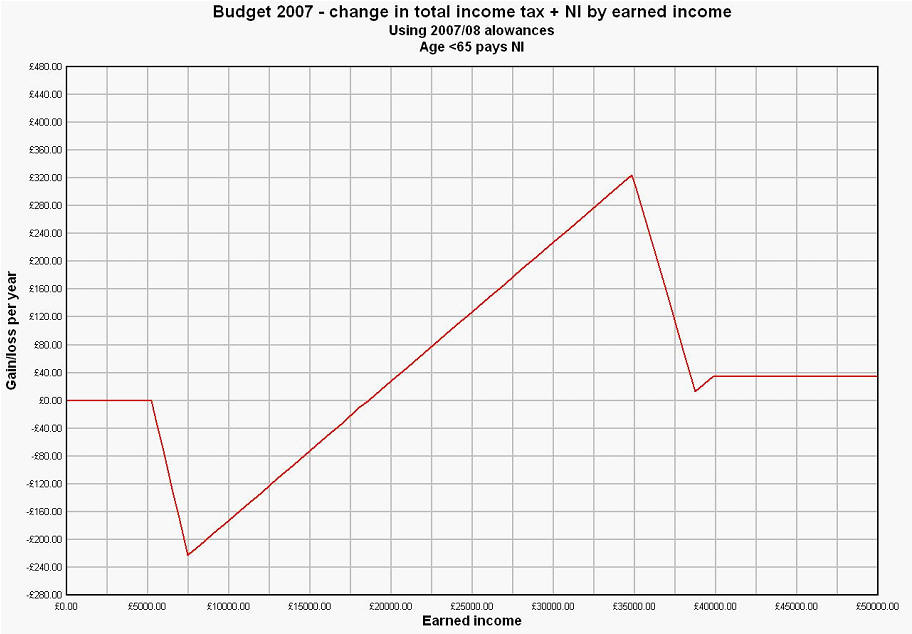

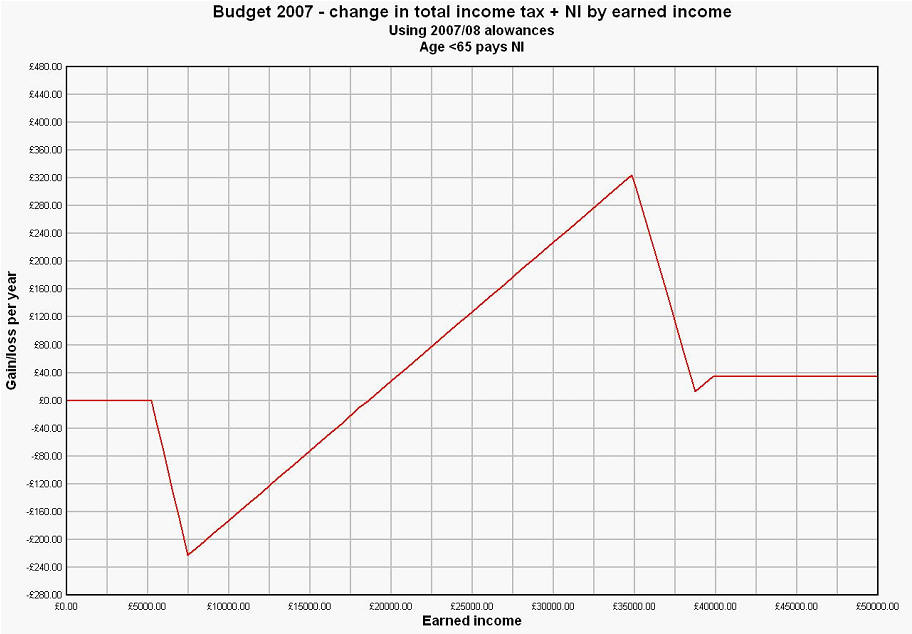

In fact the figures show that if those rules had applied this year – and at the moment that’s all we can do – then anyone earning less than £18,605 a year – about three quarters of median earnings will pay more tax next under the new rules. Someone earning a modest £7455 a year – about £143 a week – will lose the most. They will pay an extra £223 a year – that’s £4.29 a week – in income tax. And remember they are working for about 26 hours a week on the minimum wage.

At the other end of the scale people will do rather better. Someone earning £34,840 – about 1.4 times median earnings – will gain £324.70 a year around £6.25 a week – and because of changes to NI those advantages will then diminish so that people earning more than £39,825 will see a modest reduction in their tax of just £34.40 a year.

Here is that graph in figures.

High income people who pay no National Insurance. — People over pension age with large company or dare I say civil service pensions — will pay £424.40 a year once their income exceeds £39,825.

Now I make those points because next April is going to be a tough time for the low paid. Yes their minimum wage has gone up by the odd sum of 17p an hour – just under £7 for a 40 hour week. But people on the minimum wage they will end up paying more than £4 a week in extra tax next year – not because they are earning more money but because tax is rising for the low paid.

So the tax system is becoming more biased towards wealthier people. Broadly speaking by 2009/10 this change cuts about £1 billion off income tax and that is mainly given to those earning median wages or more. And I might also point out if you’re thinking what about the social fund that many people on pension credit pay tax as well as getting pension credit and they are exactly at the leave here who lose money from this change increasing demand from the over 60s on the SF.

In Britain the gap between rich and poor is growing. And the gap is not just in money. It is also in access to credit.

A great deal of the wealth that we see around us – and by that I mean the 70% of the population who are called home owners, the people who have good new clothes, who have electronic gadgets in every pocket, and who spend money going out enjoying themselves – a good deal of the wealth that buys those things and those services is not their money. It is borrowed money.

Even the Government puts borrowing at the heart of the UK economy.

The Government’s White Paper on consumer credit published in December 2003 began with these words

"Consumer credit is central to the UK economy."

In other words we have borrowed our way out of a recession.

So there is an argument which says that poverty today in Britain is not just lack of immediate cash. It is also lack of access to credit. And broader than that lack of access to banking.

Ten years ago it was possible to avoid banks altogether. Benefits were paid in giros or order books you cashed at the Post Office. Wages were still paid in cash to some people – and I don’t mean the dodgy wages handed over in used tenners, I mean official payroll wages with deductions for tax and pensions. Not any more. Benefits are paid almost exclusively into bank accounts. Wages are paid the same way.

And when it comes to paying bills or debts penalties are being introduced to penalise those who pay by cash or even cheque. Direct debit is what companies want. Not only is the payment certain it is certain on day the company chooses.

Some companies, especially the gas and electricity suppliers, offer a discount on your tariff of around 5% if you pay by direct debit. But the growing trend now is to impose penalties on people who have the temerity to pay any other way.

It is getting harder and harder to avoid the banking system. It reaches into every household. And as it does that it changes its nature.

Banking is no longer the optional preserve of the better off. It is a utility. Just as electricity or water or, in towns and cities, gas is piped to every home so banking is becoming an integral part of our lives. And with that comes new responsibilities.

When I was campaigning on fuel poverty in the 1970s we argued against disconnection of electricity and gas. The normal response then when a bill was unpaid was to send round the man with a pair of insulated pliers. As a result of those campaigns rules were introduced which banned disconnection of pensioners in the winter months. And today very few people are disconnected. It is no longer an issue. More than ten years ago disconnection of water supply was banned – it used to be banned but the right to disconnect was introduced with the privatisation of the water industry.

And even in banking there has been a move to try to make bank accounts available to everyone.

All the banks now offer what are called basic bank accounts. Now these are not defined and they offer a slightly different range of services. But no High Street bank should refuse a bank account to anyone. In the past if there wasn’t a profit to be made then many poorer people were sent away unbanked.

So there has been an attempt to treat banking like a utility – something that we all should have and indeed all need to have.

Basic bank accounts do allow access to some of the basics of life. They all allow direct debits so you can take advantage of lower charges. And they all allow you to have a cash card. A very few of them let you have a debit card – but it is a pretty junior sort of debit card Visa Electron, Solo or Maestro not accepted everywhere especially online and which makes sure you never take money out that you do not have. Because none of these accounts allows you to go overdrawn. That creates problems if for example your direct debit falls due and there is not enough money in the account to pay it. The payment will be returned – and the bank will charge you for doing that.

I haven’t done a comprehensive survey. But one example. Barclays.

If you or I have a Barclays account we can go overdrawn by £25 without arranging it and without a penalty. So a small payment overdrawn will not be returned and you will not be charged. On some accounts that £25 buffer is £250 – no fees no penalty. But on the basic bank account there is no overdraft.

So if your direct debit is not met the payment is returned and you are charged £15. That will wipe out any advantage from paying by direct debit. So you have to be able to keep a balance in there to make sure you can pay those bills. That means not only having some spare cash but being organised enough to make sure it is there when the bill falls due.

And on that spare cash Barclays and most of the other banks will pay you zero per cent interest. At least on other accounts they pay 0.1% - or rather more in some cases. And while they pay us nothing or 0.1% they lend out that money on the overnight markets at up to 6.25%.

So it’s banking Jim but not really as you or I know it. Because there is no access to credit. Now of course access to credit comes at a price.

If you have an ordinary Barclays account and a payment is returned then you will be charged £35 and a punitive 27.5% on the overdrawn balance. As you will probably know those high fees and high rates are the subject of court action by the Office of Fair Trading. And to Barclays credit for basic bank account customers it does charge £15 rather than £35. But as a proportion of weekly income that charge can be huge. For someone aged 22 on JSA of £46.85 a fee of £15 takes a third of their weekly money. And it can mount up. Barclays has confirmed that this is a daily charge.

So if a payment is bounced one day and other is bounced the next and another is bounced the next– that’s a week’s under-25 JSA just about gone.

So although the banks are happy to operate basic accounts, they are not willing to pay interest on the credit balance and they are not willing to allow any even temporary or inadvertent overdraft.

That means low income families are plugged into half the banking system but not the other half. Access to small overdrafts – free in many cases – is an essential part of managing in a non-cash economy. When you are managing your money in cash with ten pound notes and coins – you can count how much you have left and you know when it has run out. But if you are dealing with numbers in a bank account then without full online access – which also comes at a cost – it is much more difficult to manage that low income accurately.

And there is another way that these low income customers are discriminated against. Go onto any bank’s website and you won’t get a loan of much less than £1000 for a year.

I looked at the comparison website MoneyFacts and once I’d bypassed the standard offered best buy tables of £10k over 5 yrs and 5k over 3 yrs.

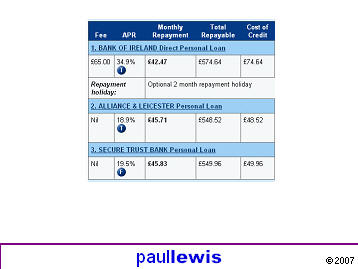

I found just three for less than £1000.

And note that the top one has an arrangement fee of £65. The other two don’t but rates are at the high end.

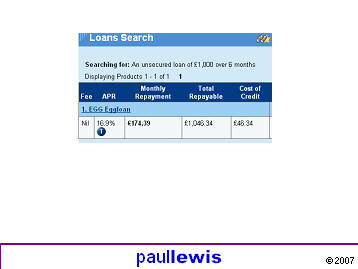

And you can find just one loan over six months and that was £1000 from Egg at an APR of 16.9%. It would cost you £46.34 to borrow that with six monthly repayments of £174.39 a month.

So short term, small amounts to buy school shoes, a washing machine, or to replace an iron or buy a bed are just not available from the banks.

So that forces low income families to the doorstep lenders. These are legal companies, in fact the largest of them, Provident Financial, was briefly in the top 100 companies – the FTSE 100. Now it’s just below that. But still a big company. So we’re not talking loan sharks who enforce payment with baseball bats. We’re talking responsible, respectable publicly listed companies.

I mentioned the Barclays unauthorised overdraft interest rate of 27.5%. And if you shop around you can do worse than that – Cooperate Bank – the ethical bank – actually charges 29.9% and LloydsTSB 29.8%. Many store cards and some credit cards charge similar amounts. But these pale compared to the interest rates charged by Provident and others. They specialise in small loans – up to £800 in Provident’s case – over short periods – either 56 weeks or 31 weeks – so a bit more than a year and bit more than six months. We’ll see why those periods in a minute.

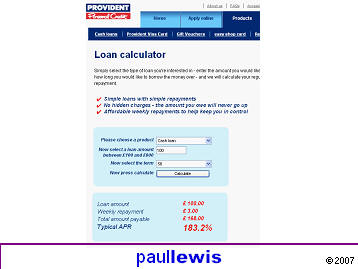

For example if you borrow £100 over 56 weeks it costs you £3 a week. And a friendly person, probably someone you know from your area, will call round every week to collect it. £3 a week seems affordable. But as the website helpfully tells you – because by law it has to – when you work out £3 x 56 you get £168. In other words you are paying £68 for the loan.

And the APR is a staggering 183.2%. Of course you can reduce the cost by paying it over 31 weeks instead.

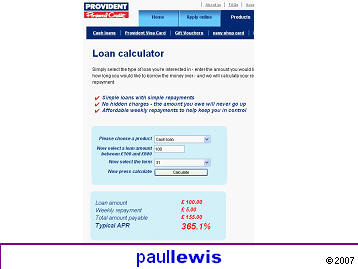

Then you pay £5 a week and over 31 weeks that is £155 so it costs you a bit less, £55. But because it is over a shorter period the APR – the annual percentage rate – is – well I called the last one staggering I’ve run out of adjectives now – 365.1%.

People take these loans for three reasons. First they are there, there are few credit checks, no difficult interactions with the banking system. Second, the amounts are simple – can I afford £3 or £5 a week per £100 borrowed (and that’s why the periods are odd so that the weekly payment is a nice round sum. And third, the payments are collected by someone who calls round, in cash. So you just have to remember to set aside three pound coins or a fiver for when they call. So it’s all jolly convenient – but you are making APRs of 183.2% for Provident.

Now Provident will say that the whole APR system is loaded against them. First, on short-term loans it exaggerates the rate. Second, by law Provident has to include in the cost of borrowing the money the cost of collecting the payments. And that is very expensive because it is done in person. In Fact it takes just under a quarter of Provident’s revenues 22%. And Chief Executive Robin Ashton told me that there were other hidden costs with that high APR.

"Unlike most other lenders, if the customer faces changed circumstances and wants to reduce repayments or to reschedule the loan, we enable the customer to do that at no additional charge whatsoever."

Well no, except that the interest rate of 183.2% carries on more money and over a longer period. Just before that he said "in our case the service charge includes the cost of credit insurance in the event that the customer dies or has changed circumstances and wants to reschedule the loan."

So the cost you are paying includes insurance in case you die half way through the loan. Now who does that benefit? Provident. Who pays it? You.

He also made the point, which is fair enough, that small loans are more expensive to administer per pound lent than bigger ones.

And there’s another cost he didn’t mention. Provident has a 30% default rate on its loans. Despite that and the other costs Provident did make a profit of £127.5 million on its home credit business in the UK in 2006. So all those costs including the defaults are paid for by its other customers through that 183.2% APR.

Robin Ashton spoke to me in 2004 when I made a programme for Radio 4 called the Price of Poverty which looked at the high cost of credit to low income families.

I said at the start that when I first got involved in poverty issues I thought the answer to poverty was easy – you gave poor people more money. And thirty years on I still look for simple solutions to these big problems. So if Provident charges 183.2% APR – and there are many others offering similar deals – I tend to think why not simply put a legal limit on the interest rate that can be charged.

And when we looked into the price of credit to poorer families we asked that question. Why not? And the surprising answer was that in some parts of the world they have done just that. The one we went to was Germany. Not a very different economy from ours. There the highest interest rate a bank could charge was around 20%. It’s worked out in a fairly complex way – each month the central bank looks at all the rates charged by all the banks, ignores the highest 5% and the lowest 5% of these prices, works out the average of the rest and then the upper limit is one and a half times the average. So if the average is about 14% then the cap is about 20% as it was when I was there.

I talked to a lawyer Kerstin Föller who works in the German equivalent of the Citizen’s Advice on debt problems and told her what rates could be charged in the UK.

She replied "Oh my goodness, I mean that’s unbelievable. I can’t even think about it. I mean it’s totally out of range."

In the UK strong arguments are put up against an interest rate cap. The Government and some academics who have studied the problem believe that if you did impose one then Provident and other similar doorstep lenders would disappear. In their place would come the loan sharks, the illegal lenders with their uncalculated APRs and their brutal means of debt recovery.

They also say it’s up to customers. They like Provident and the others, hundreds of thousands of loans a year are made for hundreds of millions of pounds. They provide a valued service.

When I put this to professor Udo Reifner, who had campaigned for a cap in Germany and was at the trial when the courts made their historic decision more than twenty years ago that implemented it, he said this

"Look if you have somebody in the desert and you offer him dirty water and he’s very thirsty he will drink it. So the question is why do we do deserts and dirty water? If you have no choice, you take what you get and that’s the problem."

I said earlier that the banks are in a new relationship with us now. They are not a business we can use or ignore, their services are so central to our lives that they are a utility, a ubiquitous service. Yes they are private companies. But so are the water companies that are not allowed to disconnect. So are the electricity and gas companies who have codes of practice and rules about when they can refuse supply. And it has to be said that the profits of the banks put those of other utilities in the shade.

In 2006 the top ten UK High Street banks made more than £40 billion in profit. A return on capital of around 15% to 20%. The big five dominate of course but the little five do pretty well and below them are five more minnows. Now that total is global profit before tax. If you just take UK retail banking – that’s you and me and our money – it’s around £13 billion.

With profits of that size I see no reason whey the banks should not be obliged to offer small, cheap and yes unprofitable loans to people on very low incomes. Already the Government has imposed a windfall tax on utilities, has forced the banks – using the threat of a windfall tax on profits – to offer basic bank accounts to just about anyone who asks for one. So I see no reason why it can’t go further and insist on the banks taking this next step towards financial inclusion. And as a quid pro quo it could impose a credit cap to push the doorstep lenders into a different way of lending. Fixed perhaps at the rate which the OFT has already decided is high enough for Store Cards 29.9%. That is enough to allow any bank to make money. And a major step towards financial inclusion for some of the poorest households.

And where would that leave the social fund? Well very necessary. I mentioned the rates charged by Provident earlier.

On a typical social fund loan of say £350 the repayments would cost £10.50 a week for 56 weeks total cost of £588 – costing £238 or £4.58 aq week. Using the Alliance & Leicester unsecured loan for £500 as a model, borrowing £350 over 12 months would cost a total of £401.80 over 52 weeks. Costing just £52 or £1 a week. And of course under the social fund £350 will be paid back over about 32 weeks on IS or about 49 weeks on JSA at no extra costs just £350.

But there are ways in which the SF urgently needs reform. The SF has become the direct antitheses of the Provident model. Not just because it charges 0% APR. But because while Provident is all personal contact and personal touch, the Social Fund is now an anonymous rule based phone service. And a system where nearly half the claims reviewed are changed and where half the claims referred further to the Independent Review Service are overturned is clearly not working as well as it should even within its own rules

But the overwhelming need for the social fund is for more money. Now ideally that should be a big increase in the grant money. When you are trying to bring up a family on less than £50 a week for each person you have no spare cash to deal with contingencies. So the paltry £141 million for grants should be increased. While loans are made, the loans budget – which is all basically recycled money – should be increased as well. Both rises will test the level of demand that exists, demand which is falsely kept low and rationed by the complexities of claiming.

And pay for it in the same way you pay for £1bn off income tax for the top half of the income earners or the £1.4bn slashed off IHT – not really a worry for those claiming from the social fund. Last week the Chancellor announced the overall spending limits for departments. The DWP told me yesterday that no decision would be announced on the Social Fund until April next year. But we do know that the DWP is once again the target for cuts in the next three years — 5% a year off its administration budget.

This cut is going to be achieved by moving to what it calls "Service Transformation including taking responsibility for Directgov from April 2008 and its development as the Government’s primary web portal for citizen focused e-services".

I am not quite sure what that means. But I do not think that "the Government’s primary web portal for citizen focused e-services" is going to make people struggling to live on state benefits rush out to get help from the social fund. Instead of cutting the administration of the social fund the department should look carefully at renewing a much more personal service. Taking on Provident and the others at their own game.

We’ve been on a slightly strange journey this morning. And before I end I want to mention two words that many of you have probably been expecting throughout my talk. Credit unions. There’s an old joke in nuclear physics that developing a cheap fusion nuclear power plant is 50 years away. And however much progress you make it is still fifty years away. And in this more modest social field the march of credit unions to take the field of cheap loans to low income households is always about a decade away. It has never happened. Despite changes and encouragement, grants and now regulation and a compensation scheme for savers credit unions remain as far as ever from the role many would like to see them play.

I don’t really know why. In Leeds there is a fabulous innovative credit union with a shop front like a small building society and a range of cheap loans, decent savings products and even now a current account and a Child Trust Fund. But credit unions are still too small to be even seen as part of the banking system. Yet they are run by local people. They will lend small amounts over short periods. The rate of interest is fixed at 12.68% APR (1% a month).

Now I have seen one credit union in Wales which was reaching local people. It was consciously taking on Provident and the others in its local community. Going round the estate, offering short term loans, Christmas, back to school loans and of course at much better rates than Provident. And it was chasing off the doorstep lenders. But it required a huge amount of voluntary ie unpaid effort. Without that it would not work. But on the whole credit unions do not do that. And just as building societies grow and become more like banks – or in some cases become banks. So credit unions which grow and professionalize become more like well if not banks then building societies. What credit unions need to do is to go back to their roots and become smaller, more local, more estate based to tackle the exploitation of poor people by the lenders who are not banks.

That was a small diversion into credit unions so that I did not leave them out. But I must say I do not see them as a crucial part of the solution. That must come from the money. From the banks who have billions they could spend. From the Government which has hundreds of billions it could spend – and does spend on the better off. And from a combination of the two, working together to end financial exclusion and to ensure that the lowest income families do not have to pay the highest APRs. And have the access to cheap credit which will bring financial inclusion to the poorest in society.