This talk was given xx Month 2007

The text here may not be identical to the spoken text

National Association of Pensions Funds 24 May 2007

KEY CHALLENGES FACING PENSIONS

Hello. Well after that introduction by Robin you’re probably thinking ‘who’. And it is a bit bizarre that with all this brain power at the NAPF conference you should invite a journalist of all people to open the day. So I’m flattered and I’ll do my best.

I am a freelance. And although I present Money Box on Radio 4, as Robin has said, I do not represent Money Box or the BBC. What I say is my own and I take responsibility for it.

This session is called Live Long and Prosper. Which is very kind of the organisers because that was the title I chose for a book I wrote on pensions last year. The title was based on a phrase from Star Trek of course – the traditional greeting of Vulcans like Mr Spock.

But it’s also based on Clement Freud who joked when he reached 80 that if a woman said to him ‘come upstairs and make love with me’ he now had to reply ‘I can do either one but not both.’

And rather whimsically I wondered if we would have to give the same answer to a passing Vulcan who welcomed us with their traditional greeting. Can we in fact live long – which we undoubtedly are – AND prosper. Or are they in fact contradictory?

I’m going to start with a story. About two brothers. George and Henry.

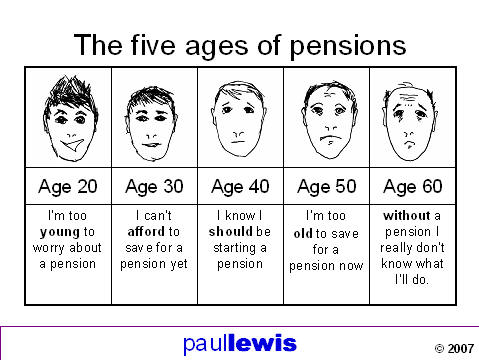

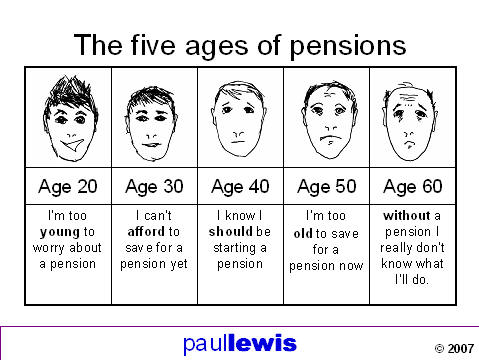

George was born in January 1937. Like most people at work in the fifties and sixties he didn’t worry much about a pension. But when he got to 40 – you remember the Pearl advert

20 – I’m too young to worry about a pension

30 – I can’t afford to save for a pension yet

40 – I know I should be starting a pension

50 – I’m too old to save for a pension now

60 – without a pension I really don’t know what I’ll do.

as the smile disappeared with the hair the worry lines grew.

Anyway George did start at 40. He put away quite a lot - £200 a month in a with profits pension fund. Twenty years later in January 1997 he reached 60. Over those twenty years he had paid in £48,000.

But his fund was worth more than five times that – £265,507. He converted it into an annuity and for each £1000 in his fund he got an annuity of £77.40 a year – a total of £20,513. He considered that a fair deal.

His brother Henry was born ten years later, in January 1947. When he was thirty he didn’t follow his brother’s lead, he thought can’t afford it, kids, house, etc. But when he reached 40 he had his Pearl moment as well and started putting the same £200 a month into the same pension fund as his brother. This year 2007 Henry reached 60. He had also put £48,000 into his fund over the same time – 20 years. But his fund was less than half as much as George’s – just £112,100. The insurance company blamed falling investment returns. And when he came to convert it into a pension he only got a pension of £41.50 for each £1000 in his pot. The annuity provider blamed growing longevity.

That double whammy of less money and less pension for each pound of it meant his pension was just £4613 a year. He thinks he has been done. Both brothers saved the same amount for the same length of time in the same pension fund – ten years apart. But George’s pension is nearly four and a half times as much as brother Henry’s.

And of course their twin sisters do even worse – a pension of £17,847 for Georgina and a paltry £4209 for Henrietta. For the same £200 a month saved over 20 years.

And this is how pensions are seen. They may have worked for a previous generation. But they won’t work for us. We don’t trust them anymore.

We might call this first reason for this lack of trust worthwhileness – because I always like a long new word for a talk. Is it worth it? It was worth it for George. He doesn’t get a fortune but he can live on his £20,513. And of course he gets his state pension which is £91 a week or £4732 a year. And with his income of £25,245 a year he is still above the median wage of a working person.

Henry gets a bit more state pension because he paid into SERPS for ten years. His state pension is £110 a week £5720 a year. More than the pension he paid for over all those years. His total income is £10,333. And if that was a wage it would put him well in the bottom tenth of full time workers.

George looks on his state pension as the icing on the cake. For Henry the state pension is the cake. What he saved up for all those years is the marzipan and icing. And although he does not have enough to live on – at least as he’d like to live – his income is too high to get any pension credit or help with his council tax. And that will still be true when he’s 65.

These figures are produced not by me but by Watson Wyatt which is why you can believe them. When I first turned them into a story a month ago a brilliant sub put this headline Brothers’ Grim Pension Tale.

It reminds me more though of Alice Through the Looking Glass. When the Red Queen told Alice

Now, HERE, you see, it takes all the running YOU can do, to keep in the same place. If you want to get somewhere else, you must run at least twice as fast as that!

Now who labelled those pensions ‘DRINK ME’?

And what depresses me at the moment is I can see a whole generation of people saving up for a pension that will end in disappointment. And as the generation of uncles and mothers and friends’ Dads who have done what we were told to do in 1988 when personal pensions began and saved for their retirement but find their pension is Henry’s not George’s they will be passing that message down the generations. And putting people off saving.

Now I touched on the reasons for Henry’s pension being so much smaller. Investment returns was one. Living longer was another. We’ll come back to longevity shortly.

One solution of course is to put more into our pension. But that isn’t what is happening. Because there is a steady move from what you pension like to confuse people by calling DB schemes – which I still call salary related pension schemes because the pension is related to your salary – to what you lovingly call DC schemes – which I call pension pot schemes because the money goes into a pension pot. Well sort of.

And as that move from salary related to pension pot happens the contributions paid in come down.

The latest figures from the National Audit Office show that people in active salary-related schemes have a total of 20.4% of salary going into the pension. But people in pension pot schemes have less than half of that going in - 9%. And less than half as much going in means less than half as much coming out. If you’re lucky. As poor old Henry found, exactly the same contributions ten years later gave him a quarter of the pension.

And in future of course the people not in any scheme will be asked to join the new National Pension Savings Scheme or as the Government wants to call it in the interests of clarity the ‘personal account’.

I asked John Hutton a year ago or more if that really was what he was going to call it and he said ‘no of course not it’s a working title.’ Last week I spoke to a senior civil servant working on the scheme and asked him and he said well it was a working title but it’s kind of stuck because every alternative is worse.

When these working title personal accounts begin here is what the Government says will happen

8% goes in - not much less in total but the burden has of course reversed. The employer gets away with half as much as the average in current schemes and the employee pays in twice as much. But the total 8% not much different.

Like so many Government claims that claim of 8% is true but misleading. No-one will pay 8% into the personal account. It is 8% of a band of earnings which, on this year’s figures, runs from £5225 to £34,840. And the most that can be paid in for someone on £34,840 is 6.8%. For someone on average earnings about £24,000 it’s 6.3%. And for someone on low earnings, say £14,000 its 5%. Split between employer and employee. So the most the employer will have to pay is 2.6% but they’ll get tax relief on that so it will cost them either 2% or 1.8% depending on their corporation tax rate. And phased in over three years.

Last year I did an exercise with Tom Ross the actuary – I’m tempted to say The Actuary – doyen of actuaries – Past President of the Faculty of Actuaries, on what we had to save for a decent pension. His take on this was refreshingly simple. It goes like this. Overall wages rise by about 4.5% a year. And by the time you have taken off commission and charges investments also grow by about 4.5% a year. So let’s assume that the growth in our pension pot will roughly speaking be the same as the growth in wages. That simplifies things a lot. And let’s forget annuities and just spend the money over the balance of our life. Again, growth will pay for inflation proofing.

I turned Tom’s equation – which he did in his head over the phone because although actuaries have proved rubbish at predicting the future they can do arithmetic – I turned it into a spreadsheet which I rather fancifully called the Ross Ice Sheet. Well, it was a spreadsheet. It is based on a formula by Tom Ross. And when you look at the answers it gives, the shiver that goes down your spine is like standing in Antarctica in a string vest.

Let’s take someone on median earnings – that’s the middle of the income range so if you stick a pin in the working population the one who goes ouch is earning about £24,000. Suppose this person starts worrying about a pension at 30 and they want a modest pension of half their earnings and at age 65. Modest enough demands. What do they need to contribute each month from now on?

The Ice Sheet says you would have to save £4235 a year, £353 a month, almost a fifth of their pay.

And if they want two thirds of their salary then it is £5333 or £444 a month, nearly a quarter of pay.

Would any of you honestly go up to a person on £24,000 a year and ask them to save not £20 a month, not £100 a month, not £250 a month but £353 a month? Still less £444 a month? It’s not going to happen.

And that is why the government has fixed the contributions to its sort-of-compulsory pensions so low. They’re all it thinks people will pay. But it won’t buy them a decent pension. If you pay 6.3% of your whole income into your personal account you will get a pension of 16% of your pay at 65. And even if you start at age 20 – which you sort of should now – you will get 20%. That’s a pension of £4800. Less than the basic state pension. And a lot less than what the pension will be in future when you can’t contract out.

You can try out the Ross Ice Sheet here

www.acblack.com/livelongandprosper

Now this is a big approximation and I can see you all writing down a list of ‘The Things Lewis Forgot.’ Luckily for me by the time anyone discovers if it is right or not the only way to complain will be to call on the local vicar who will point out my resting place in the overgrown corner of the churchyard reserved for atheists.

But I take comfort from the fact it gives very similar results to two other sources. First a report from the House of Lords Select Committee on Economic Affairs in January 2004 which gave these results.

|

Starting age |

25 |

35 |

45 |

55 |

|

Men |

17% |

24% |

37% |

72% |

|

Women |

19% |

27% |

42% |

84% |

And of course it is also very similar to the amount that goes into salary related pensions when teams of actuaries work out what is the least a company can put in and get away with it. I am sure that people here in the pensions industry know perfectly well that to make a gesture towards meeting the guarantees of salary related schemes you have to put in about 20-25% of pay. That is what’s needed to get a decent pension.

So what is the point of encouraging people to save 6.5% of their income towards their retirement? They are going to be very disappointed.

There is an answer to this problem. When Henry enquired about the fact he got so much less pension for his pot he was told ‘longevity’. My birthday is in April but in November I always look forward to a special present from Chris Daykin the Government Actuary.

Each November he publishes – actually now it is the Office for National Statistics – the latest figures on life expectancy.

Last year, using tables published the previous November my expected date of death was 23 February 2028. Half the people of my age in the UK will die before that age and half after. If I retire at 65 that gives me 14 years ten months of retirement. But then on Tuesday 21 November I checked the new tables. And now the break even bet was that I will die not on 28 February but on 7 June.

So apart from cancelling the funeral my financial plans are completely wrecked too. An extra 105 days of retirement, 2% more, with no money.

And if we go back 21 years to when I started one of my tiny pension schemes in 1986 I only expected 11 years one month of retirement. So if my pension was adequate then – it wasn’t – it certainly isn’t adequate now to cover another 4 years 1 month – 37% more.

So as life lengthens people have to accept that retirement must come later.

If there is one short phrase that sums up what lies beneath all the anxiety we have about pensions it is these four words. We are living longer. And if you want to add anything simply add ‘and longer’. And repeat.

Every time actuaries look at what it might be in future, it has grown again. And even though they build that error into today’s prediction, next time they look it is longer still. In October 2005 the Government Actuary Chris Daykin announced that he had stopped assuming that the length of life had some ultimate biological limit. In other words, the age we live to really could go on increasing forever. Or as he put it in actuary-speak ‘Previous projections have assumed that rates of mortality would gradually diminish in the long term… However… the previous long-term assumptions have been too pessimistic. Thus… the rates of improvement after 2029 are now assumed to remain constant.’

"Now assumed to remain constant". It is the biggest change to actuarial thinking since men in breeches wandered round city graveyards writing down the dates of birth and death of the inhabitants.

And the key to making pensions better and making small savings worthwhile is explain to people that they will have to work longer. After all why should we have a 20 year paid holiday at the end of our lives? Five years maybe. Ten if we’ve been really good. But fifteen or twenty just seems to me to be excessive.

Let’s see the difference. Let’s look at a pension aspiration of half what we earn. Let’s start again at 30. With the middle income person with a pin still sticking out of them. But this time they say "if I’m going to live to 80 I’ll work til 70". Now the answer is very different.

He or she needs to save £2182 a year, just 9% of income. And if that can be shared between employer and employee – not a luxury self-employed people like me have but most do – then 6% from the boss and 3% from me sounds about right. Or if it’s a personal account 3% from the boss and 6% from me.

Realistic retirement plans make adequate contributions easier.

And that brings me on to the second big challenge.

There is a growing divide between people who have employers who pay large amounts into decent salary related pensions. And those who don’t. And more and more that divide is between people in the public sector where salary related schemes remain open and unchallenged. And where retirement age is not going up to what it needs to. And the rest of us. With little going in and the prospect of working til we’re 70.

Last year I was asked to explain the Rule of 85 which local authority workers were planning to strike over. That’s the rule which says if we’re going to pay the promised public sector pensions the rest of us will have to work til we’re 85.

That divide has to be addressed. I’ll say no more because I know it is a topic that the Question Time panel feel very strongly about.

But there is another divide which is equally important. And much less popular to talk about. Tax relief.

One of the things that Gordon Brown has been most proud of has been targeting resources at those who need them. We can’t put up the basic state pension in line with earnings for everyone. Instead we’ll target resources at pensioners on lower incomes and boost the level of pension credit in line with earnings while keeping the state pension in line with prices.

Ditto tax credits. Let’s boost low pay. And let’s devise the most complex, inefficient and expensive system on earth to do it.

But in pensions the system works the other way round.

If I choose to spend £100 out of my net income into my pension Gordon stumps up £67. So in my pot there is £167 earning interest. That’s because I am one of the lucky ones. I earn enough to pay higher rate tax, as do about 3.5 million other people. We earn more than £39,825 a year. And remember that puts me in about the top sixth of earnings – 5 out of 6 people in full time work earn less than me. And in about the top eighth of income taxpayers. And in about the richest twelfth or thirteenth of all adults. £100 from me gets a subsidy of £67 from other taxpayers.

But if I am a basic rate taxpayer I put in £100 and Gordon stumps up just £28.21. So the poorer I am the smaller the subsidy into my pension. And next year it gets worse. Basic rate tax is cut. So if I put £100 out of my net income into a pension I will only get £25 subsidy. So £3.20 off my pension, but no change to the subsidy for richer folk.

The value of the pension subsidy – tax foregone as the treasury likes to call it – is one of those wonderfully fudged figures which I won’t go into but let’s use the Pensions Policy Institute figure of about £21 billion a year. More than half - 55% of it - goes to the wealthiest eighth of taxpayers.

And there is growing evidence that now a big chunk of that 55% is going not to people on forty or fifty thousand a year but people on more like £400,000 a year. Because one of the things that the changes last April did was to enable people to hide up to £225,000 – this year – in a pension and pay no tax on it. Then draw £56,250 tax free in cash next year. And keep the rest intact and draw nothing from it while it is invested for ten years. And I am sure you all know better than me that many of the record pension contribution figures which have been reported in 2006/07 have been partly due to people in their 50s and 60s putting vast amounts of money into their pension.

There was one mystery about the pension reforms of April 2006 – well there were lots like SIPPs, ASPs, Primary Protection – but they’ve been sorted out now. The remaining puzzle is what did the A in A-Day stand for.

We now know that it stood for Amazing-tax-breaks-for-the-rich-Day.

And this higher subsidy for the better off will even extend to personal accounts. Higher rate tax relief will be available for those who pay it. And at that level the net contribution by the employee and the contribution by the employer will be exactly equal. With low costs, an employer contribution and higher rate tax relief PA will be a no-brainer for those on £40,000 a year or more as part of their pension planning – but a real puzzle for those on £14,000 or even £20,000 a year.

So fairness between public and private sector – and fairness of the state pension subsidy between rich and poor.

If the public see pensions as a con for the wealthy and for privileged public servants they will not want to join in.

So.

Worthwhileness

is it worth saving for a pension at 6% of your pay?

If not why are we making people do it?

how can we make employers put more into pensions to make it worthwhile?

How can we make people have realistic expectations about retirement age?

Fairness

Is it fair that public sector workers get salary related pensions based on promises which will be paid by future taxpayers?

Is it fair that pensions are subsidised by all taxpayers – with or without pensions – and that the richest get the biggest personal subsidy and more than half of it altogether?

These are the big challenges. Not whether people can put £5000 or £3000 into Personal Accounts. Not whether charges are 0.3% or 0.8%. Not who is on the personal accounts delivery authority or what tax should be levied on ASPs on death. Those are all tiny and irrelevant details.

The real challenges are about making pensions worthwhile and making them fair. And just as important once we’ve done that making them seem worthwhile and making them seem fair. So pensions once again are understood and are popular.

Thank you