This talk was given on 14 May 2007 to the Financial Services Club meeting at Lloyd's of London

The text here may not be identical to the spoken text

Hello. I’m Paul Lewis I’m a freelance financial journalist and as some of you may know I present Money Box on Radio 4.

But I do lots of other things including writing most of the financial pages in Saga Magazine and the views I express here are mine not Saga’s, not Money Box’s and certainly not the BBC’s.

If you’re curious, everything I write or say in public is on my website –and this speech and the slides to accompany it will be up there sometime tomorrow.

I’m flattered and honoured to be here. I didn’t know until recently there was a financial services club. ‘What do you do all day?’ ‘Oh I’m in financial services’ and where do you go in the evenings ‘To my club. The financial services club.’ Fascinating life!

The whole of Radio 4, where Money Box is transmitted, costs just £71 million a year. And the whole of the BBC could be comfortably paid for by the profits of any of the major High St banks. Which brings me on to the subject of tonight’s talk.

Banks. And do they treat customers fairly? I was tempted just to say ‘no’ and move on to questions.

Certainly the customers don’t think so. Here is just one week’s bank press cuttings in February this year.

So I am going to start this evening by asking not if banks treat customers fairly – that later – but if they treat them legally. Because there is a major legal battle raging at the moment between the banks on one side and customers and consumer groups on the other.

There is a new watchdog that you all have to keep your eye on. Or watch god.

She is Nemesis the Greek god of just retribution, divine vengeance. There was another picture I found, a 19th century painting where she had rather less clothing but I wasn’t quite sure it was suitable for such an impressionable audience. Over the years Nemesis metamorphosed from revenge into justice and is seen above the Old Bailey in London.

The Nemesis that has been reaching out for the banks is the Unfair Terms in Consumer Contracts Regulations 1999

These regulations are long and dull but in principle are very simple. They recognise that when a consumer and a company sign a contract there is a great imbalance of power. The company has the power – the consumer doesn’t. And because the imbalance is so great the company can only put into contracts with consumers terms that recognise that imbalance. Terms that do not recognise it or make it worse are unfair.

5. - (1) A contractual term…shall be regarded as unfair if…it causes a significant imbalance in the parties' rights and obligations arising under the contract, to the detriment of the consumer.

So not only is it now a principle of the regulator – the FSA – that banks have to treat customers fairly. In some circumstances it is a matter of law. If the terms in a consumer contract are not fair under the regulations they are of no effect. And taking money using one of those unfair clauses is not just unfair – it is illegal.

Here’s an example. On current accounts the cost to a customer of breaching the contract can be enormous. Let me give you one example. Take Lloyds TSB – I’m not picking on Lloyds – mind you it’s going to sound like that for five minutes. But don’t worry I’ll be picking on the rest later.

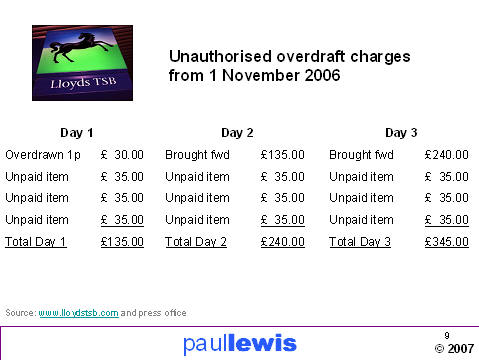

From the first of November last year if a customer of its Classic account – and there are several million – goes a penny overdrawn without permission, the bank charges £30. And if the bank decides to bounce a direct debit or cheque it charges £35 a time with a maximum of £105 a day.

So a payment is late coming in. A standing order is paid, the account goes one penny into overdraft — £30. Another payment is due. It is bounced. £35. Another £35, ditto £35. At the end of day one £135 in charges for being a penny overdrawn.

Day two dawns. Still overdrawn. Another payment is due. Another £35. Ditto. Ditto. A total of £240 pounds in charges. Next day, another three payments due another £105 added on, total of £345 in charges. So the cost of being a penny overdrawn on Tuesday is £345 by the end of Thursday. It’s worse than parking in the City.

Now this person has been careless, perhaps foolish. Three days late with money going into her account just at the time when her standing orders and direct debits are due.

Three days. By coincidence the same time it takes the banks to move money around the banking system. It is perfectly possible that she tried to move the money into her account but it has taken three days for the banks to achieve that simple objective. (NB LloydsTSB does give instant credit on certain kinds of payment into some current accounts).

I can go into a jewellers in Acton tomorrow morning, pay in £100 and by late tonight a man on a bike will deliver those funds to a family in a village in Bangladesh – and remember their time is six hours ahead. But the banks here still take three days – excluding Saturday, Sunday and of course Bank Holidays when, like the rest of us money likes a bit of a lie in.

One of the things about these charges, apart from the amounts, is that banks are unique as a retail business. Because they hold our money. And when they want to levy a charge they don’t ask for it or send a bill – they just take the money out of our account.

If Barclays sold groceries it would take our purses as we walked in. Then before we left it would take enough to cover the cost from our own purse. And give us our change three days later when it had cleared through the till.

The Competition Commission has been looking at retail banking in Northern Ireland. It is very different there – different banks, different systems, even their own banknotes. The final report is due out in about 12 hours. But one thing we expect to be in it is very radical.

It proposes to make the banks give customers 14 days notice of the charges levied on their accounts. That’s not quite sending them a bill. But it is a radical departure.

So if the bank is three days late with a payment, it’s a shrug and that’s how the system works. If we are three days late with a payment it’s £345 in fines taken from our money without a by your leave.

Now that seems unfair to me. But is it illegal? Here is the UTCCR 1999 again.

5. - (1) A contractual term…shall be regarded as unfair if…it causes a significant imbalance in the parties' rights and obligations arising under the contract, to the detriment of the consumer.

Schedule 2(1e) of the Regulations gives examples of an unfair term under Regulation 5(5)

"requiring any consumer who fails to fulfil his obligation to pay a disproportionately high sum in compensation"

In other words the charge made for breaking the contract can only reflect the cost of the breach of the rules and cannot have a penalty added on as well.

So the whole question of whether penalty charges are legal or not comes down to the question "What does it cost the bank to bounce a payment or simply report you overdrawn." Like "What is the meaning of life?" it is very simple question to ask. But a very hard one to get an answer to.

As a journalist I’ve tried. But on this topic the banks won’t be interviewed. They always put up the British Banker’s Association which speaks for the industry but cannot answer questions about individual policies. Last year I asked Ian Mullen, then chief executive, of the BBA about banks’ penalty charges he replied

"the banks believe that they have a fair, lawful and transparent system"

And when I asked specifically about a charge levied by Halifax - £39 for bouncing an item – and whether it was more than the cost to the bank he replied

"Well I can’t go into specific banks and their charges because you see each bank has its own system of charging."

But when Lloyds TSB announced those new penalty charges on its Classic current account last November, it was willing to put up Gerard Schmid head of current accounts to come on Money Box to explain these new charges. It was the question I had to ask. Here is how it went.

LEWIS: And let me ask you about the charges - £30 if you’re a penny overdrawn; £35 to bounce a payment. Does it actually cost you that much because if it doesn’t the OFT could tell you those charges have to come down?

SCHMID: Well as the earlier discussion alluded to, the OFT has not had a view in terms of whether these charges are …

LEWIS: No, but I’m asking you does it cost you £35 to bounce a payment?

SCHMID: There are a number of decisions that the bank has to undertake in terms of choosing whether to decide to extend credit when a customer doesn’t have an overdraft facility with us or whether to choose to bounce the cheque, so there are a number of complicating cost factors that are embedded in this decision that we do have to make.

LEWIS: So yes or no, does it cost you £35?

SCHMID: I think the way to think about it is a lot of these charges are completely avoidable for customers.

LEWIS: Is it yes or no?

And then a very strange thing happened. The head of current accounts at LloydsTSB just sat there in silence. As the transcript indicates

(Silence)

So I tried again

LEWIS: You’re not saying?

Once more, silence.

I thanked him and he left, in silence.

So on this one central question of legality – when a payment is bounced, does it actually cost the £35 you charge your customers – the Head of Current Accounts at Lloyds TSB sat in silence.

Of course if you are interviewed on live radio "You do not have to say anything, but it may harm your defence if you do not mention when questioned something which you later rely on in court."

That caution of course for criminal acts. But it did strike me that if these charges are not lawful then someone who takes them could be breaking another law. The Theft Act.

s.1…dishonestly appropriating property belonging to their customers with the intention of permanently depriving them of it;

Fortunately there is a defence.

s.2 A person’s appropriation of property belonging to another is not to be regarded as dishonest -- (a) if he appropriates the property in the belief that he has in law the right to…

So as long as executives believe these charges are legal then that’s OK.

Not that I’m suggesting that anyone in the banking industry or the people I’ve mentioned are guilty of theft or any crime.

Incidentally if you want to hear a LloydsTSB executive lost for words it is preserved for posterity at www.bbc.co.uk/moneybox look for 7 October.

As I said I’m not picking on Lloyds TSB. Its charges are not exceptional. And I’m certainly not picking on poor Mr Schmid. Because the truth is the banks dare not answer that key question. Their only response on whether their charges reflect the cost – in other words are legal – is to remain silent.

And it has extended this policy to the courts. Here of course it is harder to remain silent – once the hearing starts. So the banks have pulled out all the stops to make sure they never do.

It was more than a year ago – February 2006 – that Money Box first reported that Govan Law Centre in Glasgow claimed that penalty charges on current accounts were illegal and they were recovering charges for people – they even had the first form letter to make the claim.

Since then the Daily Mail, the Daily Express, The Independent, the Money Programme on BBC1, and Which? have joined in and there is now a major campaign to encourage bank customers who had these penalty charges taken from their accounts, to reclaim them. Websites have sprung up specifically to help people such as www.consumeractiongroup.co.uk and www.penaltycharges.co.uk. Between them they claim that 10,000 of their users have reclaimed £13.6 million from the banks. And another website, www.moneysavingexpert.com, has also joined in and told me today that more than three million form letters to reclaim the charges had been downloaded.

The campaign has grown to such proportions for one simple reason. Because the banks will not let the matter be tested in court, they pay up. Which? says that 85% of people reclaiming charges are successful. Other campaigners say that if you persist you will always be successful. Certainly no case has been tried in the courts. Despite some people recovering vast amounts. In April NatWest refunded a Norfolk businessman £35,987.94 including interest.

When I spoke to Angela Knight, now the new Chief Executive of the British Bankers’ Association, she told me that the banks "of course had their own legal advice that the charges were fair and lawful" So would they publish it? "No. It’s private advice."

Not only won’t they publish it no bank has had the confidence to test it in court. One spectacular failure of nerve occurred just three weeks ago. On 26 April the Mercantile Court in Leeds was due to hear 77 claims for refunds ranging from £100 to £12,000. But all were quickly settled after Judge Roger Kay suggested the banks might like to let one test case go forward and pay the claimant’s costs as well as their own.

A few weeks earlier Judge Andrew Kearney sitting in Bristol was so annoyed with Lloyds TSB that he took the highly unusual step of ordering it to pay costs of £85.41 to customer Vivien Lloyd on top of her refund of £655 in penalties. The judge said the bank was ‘acting unreasonably’ after it allowed the case to proceed to court but then settled as the hearing opened.

Other attempts to get a court to hear the legal arguments are being made. Barrister Tom Brennan is pursuing NatWest for damages as a way to force the bank to defend its policy in front of a judge. He was offered £4000 if he dropped his claim for £2500 in penalty charges and interest. He refused. His case is still wending its slow way through the courts – due back in the Mayor’s and City of London Court a week today.

A small chink in the banks’ unified stance was glimpsed earlier this year when Alliance & Leicester came close to admitting its penalty charges were too high. A customer, who wishes to remain anonymous, had claimed a refund of £2035 in penalty charges which at Alliance & Leicester are £25 for going overdrawn without permission and another £25 for each payment bounced. But in a letter sent in January the bank said "A recent report commissioned by the BBC claimed the cost would be no more than £4.50" and offered to recalculate the charges at that price and refund the difference of £1558.

That research was done for the Money Programme shown on BBC1 on 12 December 2006. It brought together Philip Molyneux, Professor of Banking and Finance at the University of Wales, Professor John Struthers of the Paisley Business School and Ian Jarritt, who used to be a senior executive at NatWest responsible for the branch network and commercial banking in the Channel Islands. They estimated that the highest cost for bouncing a cheque that could be justified was £4.50, while stopping a direct debit or dealing with an unauthorised overdraft could cost no more than £2.50. A similar study, done by a former employee of Yorkshire Bank, put the cost even lower at £2. The average amount charged by the banks is £34.

Now into this battle has ridden the Office of Fair Trading. The OFT’s first skirmish over bank charges was last year. It took a look at the penalty charges by credit card providers and in April last year the OFT decided that they were acting illegally. By charging excess penalties when we went over our credit limit or our monthly payment was late. Typically that penalty was around £25 a go. The OFT said that was too much under the Unfair Terms in Consumer Contracts Regulations.

The OFT did not say what a fair charge would be. Not least because the banks wouldn’t tell them what it cost for their computers to churn out a letter saying ‘your payment’s late and the charge is £25’. The banks just said ‘we are acting lawfully’. And when pressed added ‘we are acting lawfully.’

So the OFT plucked a figure out of the air and warned that if any credit card provider charged a customer more than £12 then it might launch an investigation into that bank’s costs and make a formal ruling on what it should charge.

The last thing the banks wanted was the OFT using its powers to burrow away in their books and discover the real cost of their computers generating a letter which is printed, enveloped, addressed, pre-sorted and posted, automatically so they decided to reduce credit card penalties.

Here’s the list of credit card penalty charges just after the deadline to reduce them.

Out of 44 credit cards 38 cut their penalties to the level which they believed would prevent an OFT investigation. Just four reduced them to £11. And only two – both American Express branded cards – to £8. In other words, caught smoking behind the bicycle sheds, they didn’t wait til they got home to light up, they did it just the other side of the school gate and puffed the smoke towards the head’s study. This is very embarrassing for the OFT which is supposed to promote competition. Can’t quite see where the competitive pressure is there.

It was a danger the OFT foresaw. In its ruling it said "we are not inviting the banks to align their charges at such a threshold figure". But that is just what they did. The OFT certainly didn’t say that £12 would be legal – it just said it wouldn’t automatically investigate.

Five months later, following what the OFT called its "success" on penalty charges it launched a fact-finding exercise last September into current account penalty charges. It talked to the BBA and presumably got the same kind of answer I always have. It was widely expected to issue a report last month with a kind of maximum fee for penalty charges. But it didn’t. Instead it turned its fact-finding exercise into a formal enquiry. Now that gives it power to demand information from individual banks so the OFT can see how much it really costs to bounce a payment. Exactly what the banks wanted to avoid. And it also launched a broader market study into the whole question of what it referred to as ‘so-called free current accounts’.

That was a highly significant phrase. Because one of the things that the banks – through the BBA – have hinted at is that if they are forced to cut penalty charges they will have to recover that money somewhere and that could mean the end of free banking. But the OFT Chief Executive John Fingleton says we don’t have free banking.

When his study was launched he told me that in as many words. "Could this" I asked "be the end of free banking?" He replied

"No because we don’t have free banking at the moment; it’s mostly the banks who say we have free banking and it’s a myth. In fact it’s completely dishonest to consumers to say that banking is free because people are paying a lot of money for their banking service."

John Fingleton points out that customers earn almost no interest on the balance in their current account and that is a hidden charge. The big five High Street banks pay a standard 0.1% on balances held in most current accounts. If you keep an average balance of £1000 in it you will earn just £1 over twelve months – and that is before 20p tax is deducted. Compare that with the money earned by the bank. Banks lend this money out overnight and earn, at Friday’s rate, 5.6% or £56 over the year. That £55 difference between what the bank earns on our money and what it pays us is a hidden charge.

Of course sensible people do not keep a £1000 balance in their current account – or even have a current account that pays 0.1% – but many do. Not least to keep a buffer against those high penalty charges. Of course, they can be avoided by getting an agreed overdraft. Then you will be charged interest on the overdrawn amount at

Barclays 15.6%

Halifax BOS 18.9%

HSBC 18.3%

Lloyds TSB 18.7%

NatWest 19.41% (£1k-£5k)

which is more than three times the amount it costs the bank to borrow that money overnight.

Free banking?

Another hidden charge I referred to earlier. When you move money from one bank to another it takes at least three days. Or three banking days which excludes the weekend.

So if you make a payment each day of the week then three of them get there by day three, three by day five and one by day four. On average the payment arrives by day four. And most banks then add a day or two before you can get your hands on that money. That means the receiving bank earns interests rather than us.

Now that might have been acceptable when men in bowler hats walked round the City with sacks of cheques. That doesn’t happen anymore. And the banks make use of this float to earn interest. It doesn’t amount to much but it is another hidden cost of banking. We do not have the use of our own money for those four days.

The problem is that many customers do perceive banking in the UK as free. There are no charges for arranging or cancelling direct debits or standing orders, no charges for writing a cheque or paying one in, no charges for withdrawing money from a bank cash machine or over the counter in the UK, and no charges for running the account and sending out statements. People who manage their accounts well, never go overdrawn, keep the balance low, and do not use their cards abroad may pay a bit in lost interest, may pay something for the clearing delays, may pay if they borrow from the banks. But they perceive banking as free. And if the outcome of the OFT study means they have to pay for these things – either one by one or through a monthly fee – then they will not be pleased. Especially if people they often regard as feckless who go overdrawn without permission see their costs come down.

John Fingleton at the OFT doesn’t have much time for this argument. He told me

FINGLETON: First of all people paying an upfront charge instead of having the same money taken from them in a hidden way is not making somebody worse off, although many people will think that they are.

LEWIS: They might perceive it as that.

FINGLETON: They might perceive it as that, but we can’t just worry about what people perceive. We have to look at what the reality is in terms of is the actual financial deal at the end of the day better for consumers or not. Otherwise we’d be in the perverse position of saying well although this is a worse financial deal, because you don’t perceive it to be a bad financial deal, let’s leave that alone, and I don’t think we would countenance that.

So battles ahead. The banks of course resist these changes. And say quite firmly that the enquiry is not needed, there is competition and customers do exercise choice by moving from one bank to another. And this claim goes to the heart of what the OFT is trying to do. Although on the surface it is about fairness and legality. Deep down it is about competition. Because the OFT doesn’t have that much power. But it can refer matters to the Competition Commission. And it can order companies to change their behaviour and can levy fines of up to 10% of turnover. Billions of pounds in the case of the banks.

So is there competition?

We saw earlier one area in credit cards where competition was not apparent. Almost every credit card provider charges the same £12 penalty if you are late with a payment or go over your credit limit.

So where else might banks compete? Let’s look at overdrafts.

Authorised interest rate.

Barclays 15.6%

Halifax BOS 18.9%

HSBC 18.3%

Lloyds TSB 18.7%

NatWest 19.41% (£1k-£5k)

Unauthorised interest rate

Barclays 27.5%

Halifax BOS 28.8%

HSBC 18.3%

Lloyds TSB 29.8%

NatWest 29.69%

Not much competition in the cost of paying an item when it takes you overdrawn

Barclays £30

Halifax BOS £30

HSBC £25

Lloyds TSB £30

NatWest £30

Or of bouncing one

Barclays £35

Halifax BOS £39

HSBC £25

Lloyds TSB £35

NatWest £38

Or in the standard interest paid on a current account balance

Barclays 0.1%

Halifax BOS 0.1%

HSBC 0.1%

Lloyds TSB 0.1%

NatWest 0.1%

Now I know you’ll say there is competition here. There are many different rates of interest paid on current accounts. And that is true. But to get those rates on some of your money you have to pay in more than a fixed amount each month or pay a monthly fee. But the underlying rate is always 0.1%.

What about another hidden charge of banking. The cost of taking cash out of foreign cash machines.

Barclays 2.75% + 2%

Halifax BOS 2.75% + £1.50

HSBC 2.75% + 1.5%

Lloyds TSB 2.75% + 1.5%

NatWest 2.65% + 2.25%

Not much competition there.

Or stopping a cheque

Barclays £10

Halifax BOS £7.50

HSBC £10

Lloyds TSB £10

NatWest £10

Copy Statement

Barclays £5

Halifax BOS £5

HSBC £5

Lloyds TSB £5

NatWest £5

Normally these are quoted per page. Though in fact under the Data Protection Act there is a maximum charge of £10. None mention that in their terms and conditions.

And what about personal loans? Say £3000 over three years

Barclays – Not Known

Halifax BOS – 13.1%

HSBC – Not Known

Lloyds TSB 18.4%

NatWest 16.4%

You’ll notice two boxes are blank. Why? Well, two of the big five won’t tell you what they charge on personal loans. They check your credit rating and other information and then make you a personal offer. The only way to find out is to log on and apply. It is what they call personal pricing or risk based pricing. Hard to see how competition can be working when the cost of this key product is kept secret.

Acting legally and being competitive are just two ways to treat customers fairly. Simple and transparent products are another. So far I’ve looked mainly at the Big Five. Because they are 95% of banking profits in the UK. But now I want to turn my gaze onto a smaller bank Alliance & Leicester.

The bank has attracted a lot of attention recently with this claim.

Get our BIGGEST ever savings rate 12%.

It sounds good even after basic rate tax its 9.6% and after higher rate it is 7.2%. But it comes with a catch. So big a catch that to me this advertising seems at best misleading. A&L isn’t the first to try this on. Because this isn’t an ordinary old savings account. No. It’s a regular savings account. and it has some strange features.

You have to pay in a regular amount each month - £10 - £250

It lasts only twelve months

You cannot withdraw a penny until the 12 months is up

So suppose you put £1000 into it at 12%, how much do you get at the end? Not £120. You get just £65. Because that £1000 has to go in regularly at £83.33 a month. And although the first £83.33 earns 12% over the year, the next payment is only in there for 11 months and so earns 11/12ths of that, the next 10/12ths and so on. As it works out you in fact get £65 interest on your £1000 which is 6.5% - not 6% as you might expect. Not a bad rate but not 12%.

In fact because you cannot take money out this is in effect a fixed rate one year bond. And that is barely more than the going rate for a fixed rate one year bond. For example Halifax pays 6.26% on £1000.

It is not clear. It is misleading. It shouldn’t be allowed.

There are also other conditions with this account.

The monthly transfer can only be made from an A&L Premier Current account. That must have at least £500 a month going into it.

It is not available to existing Premier Current Account customers

o

unless they also take out a product called Save & Protect from Legal & General.Bad though it is it is not as bad as the HSBC Regular Saver offer. That offers 8% - or as the bank puts it "HSBC Bank is offering one of the best savings rates on the high street – 8% Why not get your money to work for you for a change?"

At 8% the interest is it is a third less than A&L. And over the year you get, I am told by HSBC, 4.37% on your year’s investment. That’s £43.70 if you put £1000 in over twelve months. This means that instead of "one of the best savings rates on the High Street" you are getting just 4.37% on the total you put into the account. With all the conditions that apply. That is not a great rate. That is a rubbish rate. In fact if you compare it with the similar one year fixed term accounts at moneysupermarket.com there are 146 such accounts and this one comes in at 142nd. Even compared to instant access accounts – which it is not – it barely scrapes into the top 100 at joint 91st best.

So this is not 8%. It’s 4.37%. This is not one of the best savings rates on the High Street. It’s one of the worst. This is not getting my money to work for me. It’s getting my money to work for HSBC.

These regular savings accounts are just one example of the disingenuous way in which banks treat their customers. And there is another creeping in to the way they sell us stuff. I call it complexification. Making things so complex that no-one can make a rational choice. And yet it is usually smuggled in through the very medium of choice.

Now it’s not a popular view. But I don’t believe that choice is necessarily a good thing. When I last checked there were 9508 mortgages listed on the Moneyfacts database. No human can make a rational choice between 9508 things. It is just not possible. Two is easy. Three we can cope with. Half a dozen and we have to break them down into groups and choose between the groups. But 9508?

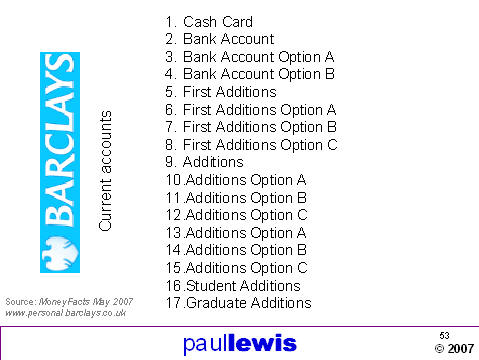

Let’s take current accounts. There are 137 in Moneyfacts. Now that would be OK, a sign perhaps of healthy competition. If 17 – more than 12% – of them weren’t offered by one bank.

Step forward Barclays.

Sorry about the vertical writing – there are so many I couldn’t fit them in any other way. MoneyFacts helpfully gave me the information that isn’t on Barclays website. The Options A, B, C refer to the duration of a zero percent overdraft rate and the amount it applies to. I am sorry I lost the will to live trying to find out if the options also applied to student and graduate additions.

And there’s no need for other big banks to feel smug. Lloyds TSB offers twelve current accounts. Cahoot offers eight. Halifax has six. Who are they competing with? Themselves?

This isn’t customer choice. It’s customer confusion. Other banks manage with far fewer. HSBC offers three – basic, bank account, and one you pay for. That seems fair enough to me. But 17?

The banks love these complex accounts because of course they can charge us. These extra Barclays accounts cost between nothing and £174 a year. So much for free banking.

In March this year the BBC Whistleblower programme sent two reporters to work at Barclays. According to one of them, who worked there for five months first in a call centre and then a branch, she saw customers misled, lied to, and treated with what she called contempt.

One of the central allegations in the programme broadcast on 21 March was that existing customers were being signed up for Barclays Additions accounts – for which they would pay between £78 and £174 a year. And if they didn’t agree – though many did – then they were signed up without their knowledge. In many cases those involuntary additions customers didn’t notice the monthly charge £6.50, £11.50, £14.50 appearing on their account. For that money they would get various items of insurance which they may or may not have wanted and certainly wouldn’t use if they didn’t know they were paying for them. They also get a preferential agreed overdraft rate of 9.99% instead of 15.6%. Useful if you need it. But one manager told the reporter that Additions Accounts were one of "the most mis-sold products" in the bank. And of course the reason staff were selling these – either openly or secretly – was targets, bonuses and commission. Paid because these products are so profitable. And of course soften up the public to the idea of paying for their current account.

The problem is this. Banks are no longer there to offer a service. Managing your account money is now a trivial occupation, best left to computers. The people who generate the banks’ profits are the ones in call centres who are employed to sell but are told to call themselves ‘account consultants’. People who can see every detail of our accounts and target their selling using that information. Following the programme some of Barclays’ sales techniques are now the subject of an investigation by the Information Commissioner. And people in the branches who are there to do much the same job.

I must add here that Barclays says it is "not in the business of encouraging or condoning mis-selling or inappropriate sales in any way whatsoever. We stamp on that when we find it because it is completely inappropriate behaviour for a bank."

What is sad about this is that the banks are throwing away a major opportunity. Otto Thoresen, the Chief Executive of Aegon Insurance, has been given the job by the Government of reporting on how to introduce what is called generic financial advice. And I am told he has the task not to see whether it’s possible but how it can be done. Free advice to everyone on personal finance.

But the High Street banks with their network of branches in every large town and still in some smaller ones too have turned their back on impartial advice. Not one of them offers independent financial advice. Most of them don’t even offer multi-tied advice. So if they can’t offer regulated advice that is impartial how can they hope to step into the breach to offer advice on finances where a sale isn’t involved? On debt. On tax credits. On the State pension. I know from the BBA the banks want to be involved. But if they don’t change and quickly they will miss this valuable boat completely.

I told you I wasn’t just going to pick on Lloyds TSB. So having picked on most of the major High Street banks, it’s time to stop.

In summary. Banks don’t treat their customers fairly.

They are accused of breaking the law, deny it, but refuse to let the courts test the legality of what they are doing.

The major banks don’t compete. They offer customers products that, insofar as they are intelligible at all, are almost identical at almost identical prices.

And they are turning themselves into commission driven marketing operations that do not offer customers clear choices or impartial advice.

Legality, simplicity, clarity. They fail on all three.

Thank you.