This talk was given on 27 February 2007

The text here may not be identical to the spoken text

FSA Retail Firms Division Conference 27 February 2007

What financial services firms need to do

to improve consumer outcomes

Hello. As you’ve heard I’m a journalist. One of the things I do is present Money Box on radio 4. I present Money Box it but I don’t represent it. I am a freelance journalist with many clients and what I say is me talking not Saga Magazine, not Money Box, and certainly not the BBC. If you’re curious about what I do everything I write or say in public is on my website.

Consumers

I’m a consumer journalist, not a business journalist. I met Tom Baigrie

recently, he founded LifeSearch the insurance broker, and he told me – I didn’t

remember – that we had met before. When I was first presenting Money Box I went

to a breakfast with some industry people organised by a PR company and was

seated next to Tom. And he says he asked me if I recognised any other point of

view than the consumer’s. And I, he told me, simply said ‘no’ and started

talking to someone else.

I hope I wasn’t quite that rude but I am sure that did represent my view more than six years ago. And I have to say thousands of emails and hundreds of letters and dozens of interviews with listeners and readers make me think that if I was asked the same question today I would give, perhaps more fully and politely, the same answer. Consumers are at the heart of what I do. And they should be at the heart of what you do. If they’re not this is what happens.

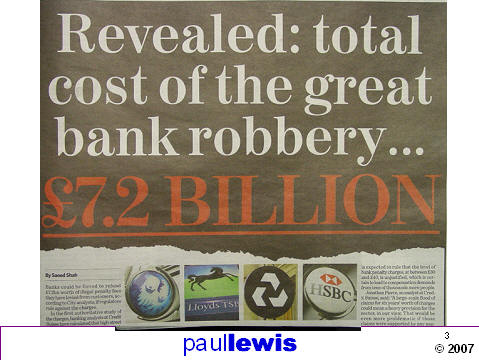

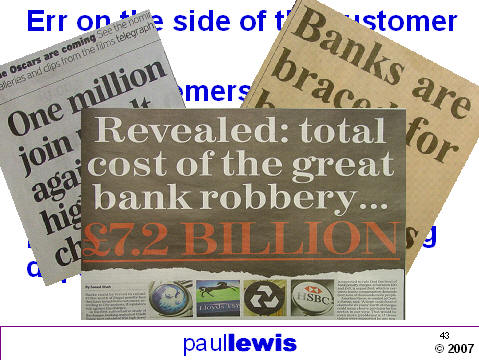

Papers from last Tuesday, Wednesday, Thursday, Friday, Saturday, and Sunday as consumers flocked to recover their penalty charges from the banks. And a late entry Monday

Consumers have started striking back. More of that campaign later.

My talk is officially called

‘What financial services firms need to do to improve consumer outcomes’.

But I would sub that down to

‘How to treat customers better’.

Over the last three years or so, consumers have moved to the heart of what the FSA does. And the move towards consumers is shown by the change Sarah Wilson has set out in the way the regulator regulates. Sarah has talked to you about treating customers fairly.

When this shift from a book of rules that was so big it broke bookshelves to a principles based regime which at its heart had the simple phrase ‘treating customers fairly’ I wondered what sort of lawful industry was it that had to be told to treat its customers fairly.

In the retail world shopkeepers know that you have to treat customers fairly. Sure you can con them once or twice – overcharge them, serve up poor value for money, sell them shoddy goods – but pretty soon they won’t come back. They will shop where they can be sure they will be treated fairly. And the stores that succeed – John Lewis, M&S, Tesco – treat their customers beyond fairly, they treat them well. Admittedly shops have had a Sale of Goods Act since 1893 whereas the Financial Services and Markets Act 2000 is just a few years old and regulation in its present form really began in 1988 at the earliest. But why does the financial services industry have to be told not only to treat their customers fairly but also has to be told in some detail by the FSA what that consists of?

It puzzles me because you are a retail business. And you know how to treat customers well. Because you are customers. We’re all customers. You know how you want to be treated in a shop. Is that how you treat your customers?

Legal

But I want to take you back a step. I want to talk to you not about treating

customers fairly but about

treating customers legally.

Now I know there are a lot of compliance officers are here. And I’ve been taken to task before by compliance officers who say ‘hey, we’re the good guys. We make sure the financial services industry sticks to the rules.’ And that is why I am saying these things to you. Because there is a new watchdog you have to keep your eye on. Or watch god.

I always like to get a Greek god into my talks. She is Nemesis the Greek god of just retribution, divine vengeance. Over the years Nemesis metamorphosed from revenge into justice – the statue on the Old Bailey in London, one hundred years old today.

|

|

|

And the Nemesis that has been reaching out for the banks is

the Unfair Terms in Consumer Contracts Regulations 1999

These regulations are long and dull but in principle are very simple. They say that when a consumer and a company sign a contract there is a great imbalance of power. The company has the power – the consumer doesn’t. And because the imbalance is so great companies are only allowed to put into contracts with consumers terms that recognise that imbalance. And terms are unfair if they make that imbalance worse.

5. - (1) A contractual term…shall be regarded as unfair if…it causes a significant imbalance in the parties' rights and obligations arising under the contract, to the detriment of the consumer.

So not only is it a principle of the regulator – the FSA – that you have to treat customers fairly. In some circumstances it is a matter of law. If the terms in a consumer contract are not fair under the regulations they are of no effect. And taking money using one of those unfair clauses is not just unfair – it is illegal.

A year ago Money Box reported that the Govan Law Centre in Glasgow claimed that penalty charges on current accounts were illegal and they were recovering charges for people – they even had the first form letter to use to make the claim.

At that time of course credit card penalties were already being investigated by the Office of Fair Trading and in April last year the OFT decided that credit card providers were breaking the law. Acting illegally. By charging excess penalties when we went over our credit limit or our monthly payment was late. Typically that penalty was around £25 a go. But the regulations say that a company cannot make a customer who breaks the terms of a contract "pay a disproportionately high sum in compensation."

In other words the charge made for breaking the contract can only reflect the cost of the breach of the rules and cannot have a penalty added on as well.

The OFT did not say what a fair charge would be. Not least because the banks wouldn’t tell them what it cost for their computers to churn out a letter saying ‘your payment’s late and the charge is £25’. The banks just said ‘we are acting lawfully’. And when pressed added ‘we are acting lawfully.’

So the OFT plucked a figure out of the air and warned that if any credit card provider charged a customer more than £12 then it might launch an investigation into that bank’s costs and make a formal ruling on what it should charge.

The last thing the banks wanted was the OFT using its powers to burrow away in their books and discover the real cost of their computers generating a letter which is printed, enveloped, addressed, pre-sorted and posted, automatically – couple of quid? – so they decided to reduce credit card penalties.

Here’s the list of credit card penalty charges just after the deadline to reduce them.

Out of 44 credit cards 38 cut their penalties to the level which they believed would prevent an OFT investigation. Just four reduced them to £11. And only two – both American Express branded cards – to £8. In other words, caught smoking behind the bicycle sheds, they didn’t wait til they got home to light up, they did it just the other side of the school gate. Obeyed the letter not the spirit of the ruling. This is very embarrassing for the OFT which is supposed to promote competition. Can’t quite see where the competitive pressure is there.

It was a danger the OFT foresaw. In its ruling it said "we are not inviting the banks to align their charges at such a threshold figure" (para. 5.5). But that is just what the credit card providers did. The OFT certainly didn’t say that £12 would be legal – it just said it wouldn’t automatically investigate.

Now of course the OFT will shortly publish its new conclusions on overdraft penalties. And more than a million customers are said to have downloaded form letters to claim back their bank charges. Believing that charging £35 to bounce a payment is illegal under the Unfair Contract terms regulations. The banks tell us they are legal – but they will not allow a single case to go to court to establish that.

Now even the judges are getting annoyed. As we first reported on Money Box four weeks ago – and which was in the papers last week, one judge – Mr Justice Collins – has tried to get cases referred to a higher court for a ruling. But the banks settled them all before the Mercantile Court could hear them. So there is still no ruling.

Let me tell you the banks’ new defence. This was put to me on Saturday by Eric Leenders, Executive Director of Retail at the British Banker's Association. They now say that in fact these charges are not penalties, they are simply the tariff for a service. So if it costs a fiver to bounce a payment but they charge their customers £35 for this ‘service’ that isn’t a penalty it’s just a healthy profit margin. Part of what it takes to boost retail banking profits by 17% in the last year at Barclays and Lloyds TSB.

But if the banks are so confident they are right, why not end the misery now and go to court? The only reason this campaign has exploded is because word has spread that the banks always pay up.

Though sometimes, people who take cases to court face having their bank accounts closed. Where is treating customers fairly there?

Exit fees

Another example of a breach of the Nemesis Regulations, affecting mortgage

lenders this time, is exit fees. I spoke to the Council of Mortgage Lenders last

summer and suggested that exit fees were a wheeze dreamt up by the

‘taking-money-off-customers-without-them-noticing department’. I repeated that

phrase on BBC1 last autumn and I got an email from someone who said ‘They exist!

My father used to work for one of the major High St banks and he did just that.

They called it the Retail Innovations Department!’

Anyway these bright sparks worked out that you could quote one exit fee at the start of the mortgage, then raise it over the years, and at the end the customer would be saddled with a bill they weren’t expecting but probably wouldn’t even notice. You pay off your mortgage and buried in the £124,853.49 settlement figures is a redemption/sealing/exit/deeds/etc fee of £200 or so. Money for nothing. As a result mortgage exit fees rose, on average, by 14% a year over ten years. From an average of £55 to an average of £205. If allowed to continue over the lifetime of a mortgage taken out in 1996 they could have risen to £1,475.

But the FSA stepped in and announced in September 2005 that it was investigating exit fees. As soon as it made that announcement, fees were frozen. Then last month the FSA confirmed that putting up the fee during the course of the mortgage was against the Nemesis Regulations. In particular this one.

So caught bang to rights the lenders agreed to change their ways and only to charge at the end the fee that had been stated at the beginning. But for ten years at least lenders have been taking money off consumers to which they had no right.

Or as we might put it

…dishonestly appropriating property belonging to [their customers] with the intention of permanently depriving them of it;

Not the Unfair Terms Regulations. The Theft Act 1968.

So this is a big deal. This is not consumer complaints, consumer rights, or even treating customers unfairly. Potentially this is theft.

Now I’m not suggesting anyone in the banking world is guilty of theft. There is a defence.

A person’s appropriation of property belonging to another is not to be regarded as dishonest — (a) if he appropriates the property in the belief that he has in law the right to…

Let’s hope the people in charge honestly believed that. Or else they’re looking at seven years. No wonder they don’t want it to go to court.

But they have still been caught out taking money they had no right to over ten years. In that time more than ten million mortgages have been paid off – nearly nine million remortgages and an apparently unknown number of mortgages that have come to the end of their term. So potentially hundreds of millions of pounds has been wrongly taken from millions of customers. Are they going to give it back?

Well no. Not unless customers ask for it. The crime has been identified. The perpetrators are known. And the lockup where they keep the goods has been traced to a vault in EC2. But they won’t actually give you your stuff back unless you ask for it. Oh, and they’re not going to say sorry either.

In future of course they won’t take your money. But they don’t need to. As soon as the FSA started investigating fees at the end of the mortgage, the lenders started putting up the fees at the start.

On a typical two year fixed rate mortgage, where competition is fiercest, the average arrangement fee was around £500 last year. Now it is £800. Here’s an example. In September 2006 Portman charged £599 on its two year fix, now it charges £999. Have costs shot up 67% in that time? Over all mortgages you can expect to pay up to £1000 just to be taken on as a customer. It’s as if Tesco had been caught making an illegal charge to open the doors to let you out of the shop and agreed to stop doing that but now charges you a fiver to come into the store instead. It may be legal – but is it fair?

Simple

There is one way in which it clearly is not fair. Humans can recognise a

very small number of objects without counting. If I put this up –

you know it’s 4. This is 5.

But this – without counting you won’t know is nine.

Generally 7 is the limit to recognise the number. Here’s 50.

There is a relationship between the number of things we can recognise without counting and the number of things we can choose between. It’s wired in. On the MoneyFacts database there are not nine, or fifty or even 1600 ordinary home loan mortgages. There are 9508. Here's that number with about 1600 dots behind it.

As that shows arrangement fees vary from nothing to £2499 – and some charge a percentage 0.75% to 2.5% of the loan. So on a £200,000 mortgage that’s from £1500 to £5000. If that arrangement fee is added to the loan it is impossible to make a rational comparison between those offers. Which is better?

It's impossible to say isn't it? And those are just four from the best buys! Already pre-sorted. And then there are free or not legal fees, survey charges, perhaps a higher lending charge – and of course the now fixed exit charge to factor in.

My view is – if you cannot make a rational comparison then making those offers is unfair.

It is part of a process which I call complexification. Giving people so much choice that they cannot make a rational decision between the options. And in my view too much choice is as unfair to customers as too little.

On the MoneyFacts database there are 9508 mortgages, 3679 pensions, 3178 life funds, 2034 unit trusts, 318 investment trusts, there are 550 medical insurance products, 500 travel insurance, 40 income protection plans – not to mention all the cash savings accounts, Child Trust Funds, credit cards and so on. No wonder people need advice.

But advice that has been complexified too.

Clear

It used to be easy didn’t it? Everyone who sold us financial products, or

investment products anyway, was either independent. Or tied. An Independent

Financial Adviser had the legal obligation to look at the whole range of

financial products and find the best one for our needs. A tied agent could only

sell the products of one bank or insurance company.

So for journalists and the public it was quite easy. Two kinds of adviser. Independent or tied. Or as we often used to say good or bad.

But the FSA decided that this ‘polarisation’ was anti-competitive and needed modernising. Before depolarisation there were two kinds of financial adviser. After depolarisation, there are, how many? Any idea? Write down what you think it might be.

Let’s start with investment advisers

They can sell you products from the

And they can act towards you in three different ways. They can

And you can pay in three different ways

So that’s three ways to relate to providers, three ways to relate to you and three ways to charge you. 3x3x3 is 27. So 27 types of investment adviser.

You can do similar calculations for mortgage advisers – the rules are similar but no Sandler products and no hybrid fees/commission. So there are 3x2x2 = 12 kinds of each. And it’s the same for insurance people. So if you just sell investments or mortgages or insurance, there are 27+12+12 = 51 different ways to be a financial adviser. If you sell two products – mortgages and insurance for example – there are 27x12 + 27x12 + 12x12 = 792. And if you sell all three products – as many do – there are 27x12x12 = 3888 different kinds of adviser.

So the grand total is 51+792+3888 = 4731 different possible types. And every one of them can call themselves a ‘financial adviser’ and some of them – I have absolutely no idea how many – can add the word ‘independent’.

And the confusion doesn’t stop here. ‘Whole of market’ is a strange new phrase that doesn’t mean ‘the whole of the market’. It can mean as few as 15 mortgage companies out of about 100. It can mean a panel of investment providers. The insurance equivalent – a range – can mean as few as six insurance companies. With insurance there are two ways to be paid – by fee and ‘no fee’ – which means commission but they don’t want you to know that because insurance sales people are allowed to keep the commission they are paid secret.

So who is sitting there selling us this product? It is, literally, impossible to know. A financial adviser may not give advice. A whole of market adviser may not cover the whole of the market. An independent adviser may not be allowed to call themselves that. And an adviser who charges fees may in fact be paid by commission.

So how do you trust your adviser to find you the best deal?

One example, many mortgage advisers – including some of the top national ones – offer whole of market; advice; for a fee, on mortgage sales. But then sell you insurance from a limited number of insurers; without advice; for ‘no fee’ i.e. commission. So out of 144 types of adviser who sells two product groups you have picked type MI aab cbb. Hardly simplification.

Some are even tied for one sort of insurance and multi-tied or sell a range for another. That isn’t even in my scheme of boxes and is in addition to the 4731 types identified! So the person who sits opposite you sells you a mortgage – quite possibly the best there is for your circumstances – you trust them, you’re grateful and then there is an offer of an insurance product. Which is not whole of market and not advised. Do most customers understand that?

No. At the moment the rules let you do this. But the principle of fairness says to me you should not. And principles should take precedence over rules.

Conclusion

So. To sum up.

Because if you don’t this week’s headlines show that customers not only want to fight back, they have the internet to help them fight back.

Because we have noticed.

Thank you

27 February 2007