This talk was given on 16 November 2006

The text here may not be identical to the spoken text

Atradius 16 November 2006

THE PENSION RISK

Introduction

Two hundred and fifty years ago if you had been in the City of London

walking near one of the many over filled graveyards you might have seen a

respectable gentleman wandering from headstone to headstone taking careful

notes. Passers-by probably thought he was a harmless eccentric. But they were

wrong. He was doing the basic research on which the whole financial services

industry is now based.

A century earlier, the mathematics he needed was first worked out in seedy

clubs in Europe where men were betting on cards and on dice. There, the new

mathematics of probability meant the difference between going home rich, - or

being fleeced.

But by the start of the eighteenth century wealthy men were realising that there

was a form of gambling which could bring even bigger rewards and was

respectable. It was called insurance. And they were prepared to risk their money

on ships foundering, on slaves arriving, on houses burning or on men dying. But

in this field they lacked the data – and the mathematical analysis – to make the

predictions they needed.

It wasn’t long before some bright young mathematicians realised that just as

over the long run you could work out the odds of dice or cards coming up in

certain ways with totals in a certain pattern, if you knew how long men lived

you could work out the correct amount to charge for insuring a life. You would

be wrong about the individual. But overall you would be right and if you set the

premium on those principles you would make money.

So they scurried around graveyards and pored over bills of mortality to discover

how long a man did live. They were opposed by the church. The time a man died

was decided not by mathematicians but by God. A point of view still held by the

Plymouth Brethren who will therefore not buy life insurance or even annuities.

One particularly clever mathematician called James Dodson applied the rules of

probability to this data and worked out the principles of life assurance we know

today. Here is his table in his paper

He was in fact the first actuary – though that term came later. Dodson died in

1757. Now this was before Watt had patented his steam engine. And just as Watt

underpinned the industrial revolution so Dodson’s work underpins the whole

financial services industry. Without it there would be no life insurance, no

annuities, and no pensions.

I start in this way because I want to talk about pensions, the crisis we have,

and why we have it, and what it means to you. Because in those City graveyards

were the seeds of the current pensions crisis.

Longer life

If there is one short phrase that sums up what lies beneath all the anxiety we

have about pensions it is these four words.

We - are - living - longer.

And if you want to add anything simply add ‘and longer’. And repeat. Fade to

white. Every time the actuaries look at our life expectancy it gets longer.

It is longer life that is changing the calculations of what we need to save. It

is longer life that affects how much those savings will give us in retirement.

It is longer life that is undermining the hopes we had of retiring earlier.

In a way we’re meeting a week too early. Because next Tuesday, the 21st, the

Government Actuary will publish his latest estimates of how long we have to

live. The latest version of his life tables.

And if last year and the year before are anything to go by, we will all be given

a few months more to live. Last year I was thrilled to see that I had been given

an extra 98 days of life. I know this because I devised a spreadsheet which

enables you to put in your date of birth and it tells you your date of death. In

2004, when I put in my birth date the spreadsheet told me that my departure was

scheduled for 19 September 2027. But when the new figures in 2005 came out I

entered the data and I now expect to shuffle off this mortal coil on 26 December

2027. An extra 98 days. Apart from cancelling the funeral it really buggers up

financial planning. Three months with no money left.

And if I go back to the year I started one of my pension plans, 20 years ago,

then a man of my age now – and this is complicated but you have to look back

knowing what you know now ie that I will survive 20 years – could expect to die

at 75 on 14 January 2024 . As you can see that is almost four years less than I

expect now.

So if I plan to retire at 65, when I started my pension I would have expected

to live on my pension for 3919 days. But now, 20 years on, in 2005 if I retire

at 65 I could expect to live 5361 days on my pension. An increase of 1442 days

or 37%. So if the pension was adequate in the 1980s by the 20noughts it is

pretty hopeless. And that is without taking account of the fact that if I live

to 65 there will be eight more years of GAD data before I retire – and the fact

that I survive those next eight years – will mean I have even longer to live on

a pension I hoped would be adequate in 1985.

So reason number one for the pensions crisis is – life is getting longer. And it

is growing faster than anyone predicted. Every time actuaries look at what it

might be in future, it has grown again. And even though they build that error

into today’s prediction, next time they look it is longer still. In October 2005

the Government Actuary (the Future Cruncher in Chief), Chris Daykin announced

that he had stopped assuming that the length of life had some ultimate

biological limit. In other words, the age we live to really could go on

increasing forever. Or as he put it in actuary-speak ‘Previous projections have

assumed that rates of mortality would gradually diminish in the long term…

However… the previous long-term assumptions have been too pessimistic. Thus… the

rates of improvement after 2029 are now assumed to remain constant.’

'Now assumed to remain constant'. It is the biggest change to actuarial

thinking in 250 years.

So when someone says ‘How long will I live?’ or if they’re feeling depressed,

‘When will I die?’ You can look at today’s tables and say If you are an adult

under 50 you can expect to live to around 81 if you are a woman or 78 if you’re

a bloke. If you are in your fifties, add a year. In your sixties, add three and

in your seventies, add five or six. Alternatively just write down 120. Because

that may be the answer too.

Now I said longer life is reason number one. It is also reason number two.

First, of course if we do live longer they’ll have to pay out for longer. But

second, and more subtle, is that we are now less certain that the estimates are

right. So we have to build in more costs to cover that uncertainty.

So growing life expectancy is a double whammy – reason numbers 1 and 2 for

pensions getting dearer.

Fairer pensions

Number three reason. And this probably doesn’t feature on anyone else’s

list. Pensions are getting dearer because they’re getting fairer. And fairness

is expensive.

At one time pension funds were there to encourage employees to stay with their

employer. They were supposed to recruit, motivate and retain staff. I can see

recruitment and retention but I never did get ‘motivation’. So it seemed

reasonable then that anyone who left the company – and the scheme – should not

have those benefits.

Until 1975, if you left your pension scheme before you retired you got nothing

back at all except the contributions you had paid in (less tax because of course

you had got tax relief when you paid them, so it was recouped by taxing them

when you took them back). The fund kept the money your contributions had earned

during those years, plus the contributions paid in by the employer. So funds

gained a lot from early leavers.

From April 1975 schemes were obliged to give people who stayed for at least five

years what are called ‘preserved rights’. In other words you could leave your

contributions in a pension fund, even if you moved to another company. You could

not add to them, but you retained the right to draw your pension when you

finally reached the scheme’s pension age. Of course that was a long time in the

future and your pension would relate to your salary when you left your job, so

it would not be very much. Another gain to the fund.

Then on 1 January 1986, anyone who left with at least five years in a fund was

given a new choice. They could take the value of their pension rights with them.

It was called a ‘transfer value’ because it could be transferred to another

pension scheme.

A couple of years later, in April 1988, the five-year period was cut to two

years.

And from April 2006, as part of the A-Day changes, the two-year wait has been

cut to just six months.

So that removes almost all the gains for pension funds from early leavers.

Over the same period, the value of any preserved pension you left in a scheme

has been increased by changes in the law.

Until 1978, the pension you left preserved in a scheme did not have to rise

between when you left and when you retired. So the scheme worked out the pension

you were due – so much percentage of your pay in say 1976 – and that was the

same in cash terms when you retired, maybe 30 years later.

In 1978, part of this pension (the bit that was in effect replacing your State

Earnings Related Pension Scheme pension) had to be increased either by the rise

in earnings or the rise in prices, though that could be capped at 5% a year.

Then from 1 January 1985 the rest of your preserved pension also had to be

increased by the rise in prices, capped at 5% a year. At first that rule only

related to the pension you earned from 1 January 1985.

Then from the start of 1991 the pension you earned earlier also had to be

increased by the same amount.

These changes all applied to people who left their scheme after the change

began. But some schemes decided to extend them to others as well.

These were of course good changes for the individuals who left. They made things

much fairer for them. But although it seems very unfair for someone who left

after eight years paying into a pension to leave with nothing more than their

contributions back and a tax bill, that was all part of the arithmetic of how

pension funds worked. Stopping the unfairness has to be paid for by someone. The

pension fund. And then of course if there isn’t enough in it, the business that

backs the scheme.

But from April this year, there is a new change to reduce the costs to the

fund. The rise of up to 5% a year has been cut to a maximum of 2.5% a year in

order to limit the sums that the fund needs to set aside to meet these costs. It

is the first erosion of the rights of pension-scheme members since, well,

probably ever.

So another double whammy. You can keep your pension and the pension your can

keep is worth more. And that means there is less left in the fund for the people

who stay to the end. Before 1975 early leavers gave a huge subsidy to those who

stayed. A reward for loyalty indeed. Someone in 1974 who left before pension age

just got back what they had put in. Now, after six months in the job they can

leave with the full value of their pension.

So just as people are living longer and can expect to draw their pension for

more years, and the pension pot they are paid from is getting smaller. Double

double whammy.

And the whammies don’t stop there.

Politics

Since the 1950s pension funds were invested mainly in shares. It was a

no-brainer. For the last quarter of the 20th century the FTSE index of shares in

London grew by 12% a year compound.

But this created another problem. As the funds grew more than expected those

actuaries again looked at them and reported surpluses. Now because money going

from a company’s profits into a pension avoided tax, there was a suspicion in

Government – a Tory government – that pensions were being used to salt money

away tax-free that could somehow be taken back later without tax being charged

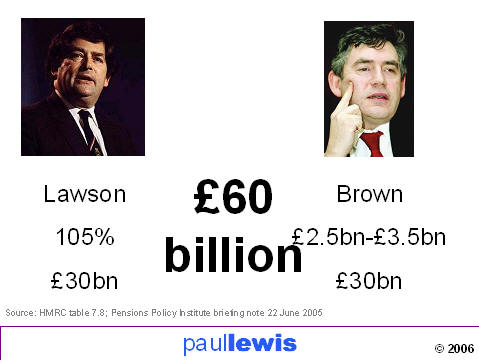

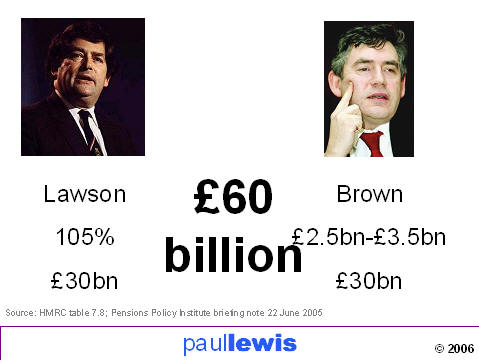

again. So this man, yes Nigella Lawson’s Dad, who by a strange coincidence has a

similar name , he decided that if a surplus was more than 5% – in other words if

the fund was more than 105% of what the actuaries said it should be – it had to

reduce the excess. Since that law was introduced in 1987/88 a total of £30

billion has been taken out of pension schemes one way or another and most of it

nearly £20 billion was kept by companies. Most of that was taken out early on,

so with growth that would now go a long way to meeting the deficits. And it was

such a short-sighted thing to do. Because if there is one thing we know about

stock market investments – they can go down as well as up. They are for the long

term. So 105% is a tiny margin of error.

So that was the Lawson raid – £30 billion. Then of course we had the Gordon

raid. Now this is strangely more complicated. And I won’t go into it. But

broadly speaking Gordon Brown’s change in the way shares were taxed in 1997

meant that pension funds lost between £2.5bn and £3.5bn a year, though that is

declining. But it was a lot of money. And by now nearly ten years on, it could

amount to as much as the Lawson raid. Total say £60 billion. And all the lost

investment growth.

So another double whammy – Lawson and Brown.

And then of course in 2000 we discovered that shares were not a one way bet.

They could do down as well as plummet. And plummet they did. By March, to half

their level as the new century dawned. Now they are moving back up. But they

fell so far that if you had put money into the FTSE 100 shares on 2 February

1999 you would today after seven years eight months those shares would be worth

exactly what they were when you put it in. So no growth in 7 and three quarter

years. Back where you started.

But despite that, despite Lawson and Brown, despite pensions being made

fairer – the main thing is life expectancy. And I say that because wherever you

look in the world, whatever pension system they have, they are all in

difficulties. Not because of investments – some of them don’t have investments –

not because of deficits – many don’t have deficits – not because of mean bosses

or stupid politicians – some of them… well OK they all have those – but they are

all heading for problems because in just about every country in the world people

are living longer.

Pensions strike back

Now the pensions I’ve been talking about are salary related pensions –

called that because the pension is a fixed proportion of your salary. Usually

the salary when you retire hence their other name DB. Sorry I’m looking for a D

or B anyone got a D or B? No. Final salary, salary related, defined benefit or

DB all the same.

These are the big boys, the expensive ones. The open ended ones. The ones that

promise a pension of a certain size. Which funnily enough is what people want. I

want to know that if I pay 5% of my pay into a pension I will get say half my

salary at, let’s be practical, at 65.

This is the pensions promise and it is very hard to meet. The latest figures

from the National Association of Pension Fund show that among final salary

schemes employees do typically pay 5% - but their employers pay typically 16%.

That’s a total of 21% of pay going in to meet the pension promise. And even with

that most pension funds have too little money in them.

I once was foolish enough to mention the fortunate position of people in the

public sector – council workers, NHS staff, teachers, and, I added, police

officers all of whom have their pensions largely paid for out of taxation. I had

a very irate letter from a copper who said “I pay for my pension. 8% every

month. I am not paid for out of taxes. Get your facts right.”

If he’d met me I’d have spent a night in the cells. In fact the cost of police

pensions is more like 25% or 30% of pay (and they pay 11% now) and that cost is

coming out of tax – council tax.

Now that’s OK in the public sector when tax does underpin the pension promise.

But in the private sector these pensions can wreck companies because they

underwrite the pensions promise.

When the Empire State Building was constructed in 1930 the steel girders were

provided by Bethlehem Steel. In 2002 it effectively went bust and was taken over

by ISG. Polaroid the instant camera company went the same way. So pensions have

sent companies to the wall.

In the US when that happens the pension is taken over by the Pensions Benefit

Guaranty Corporation. It takes over failing pension funds from failing

companies. In 2000 it had 541,000 people on its books. By 2005 that had grown to

1,300,000. In 2000 it paid out $900 million. By 2005 that had grown to $3.7

billion. And in 2000 it had a surplus of £9.7 billion and by 2005 that had

shrunk to a deficit of $23 billion.

And who will meet that? The US taxpayer – so now even private company pensions

have as a final underwriter the taxpayer.

Now here since April 2005 we have had the Pension Protection Fund or PPF. In its

first year it has taken in 98 pension schemes covering 43,000 people. It is paid

for by schemes that have not gone bust. In year one they paid £138 million and

this year it will be charging them £324 million. So good schemes paying for bad.

And some of those are in difficulty themselves. Between them they have around

£630 billion in assets. The latest research by Deloitte suggests that there is

an overall deficit in final salary schemes of £100 billion – others say slightly

less. Now of course a deficit is only as accurate as the actuaries that work it

out and the assumptions they make. There are now standard ways to work out

deficits. But at that sort of order, we are talking about company schemes being

about 14% too small.

The Government has told them they must close their deficits within ten years.

And last year companies put £20 billion into their schemes. But still that left

them £100 billion too little.

And this is damaging companies. This from cuttings in the last week.

- Sea Containers told to pay off its deficit.

- BT told it is assuming post workers die too young

- ITV’s deal with NTL scuppered by its pension deficit

and then next day

- ITV to axe final salary pensions.

And it’s not just ITV taking action. Companies all over are taking action.

- How can they cut costs?

- Change final salary to career average

- Close to new members – Companies are closing salary

related pensions rapidly. The National Association of Pension Funds says that

57% of salary related schemes are closed to new members.

- Close to existing members

- Wind up

But now there is another alternative.

Now this is a new idea and several companies are being set up to buy the

assets and liabilities of closed occupational schemes. I say ‘buy’ but generally

they are given them with a dowry. The company with the pension pays the new

company to take away its continuing liabilities. And most important to get rid

of the uncertainty. One payment and they are free.

One company is Paternoster, run by ex chief Man from the Pru Mark Wood. And

investment bank Goldman Sachs is looking to do something similar as are others.

Closed pension funds are called zombies. And the City vultures are circling.

Zombie eater in chief Mark Wood says there is a trillion pounds of assets and he

reckons a third may be snapped up like this.

When companies close final salary schemes they usually substitute them with the

alternative – what are called money purchase or defined contribution or DC

schemes. These simply store up your contributions and those of your employer in

a pension fund that has your name on it – often called a pension pot.

Cost of pensions

And when companies move from salary schemes to money schemes they take the

opportunity to cut their contributions. Here is what they pay into salary

related schemes. But when they replace them, here is what they pay.

So the total down from 21.2% to 12.8% that is a cut in the overall contributions

to about 60%. And 60% of the contributions means 60% of the benefits.

And now the Government is stepping in with its own ideas. What it calls soft

compulsion. In other words, given that 30% of people with a pension scheme

available don’t join it – and in the private sector that is even higher. The

Government wants us all to be opted in – willy nilly. Then we have to choose to

leave. Like ID cards being voluntary but to get a passport you’ll have to have

one.

And these present contributions are huge compared to what the Government has

in store. Its new plan for the future is for employees to pay in the same 5% and

for employers to pay in just 3%. So we will move from employers putting 16.1% in

to putting 3% in. And total contributions down from 21.1% to 8%.

Now this just isn’t enough.

J P Morgan Invest did a survey published this week, which asked people how much

they had to have in their little pot to buy a pension of £25,000 a year. 59%

didn’t have a clue. And one in six thought the answer was £50,000. The real

answer is – guesses – £355,000 for a bloke and about £380,000 for a woman. And

that’s for a flatrate pension which never goes up through 20 years retirement.

If you want inflation proofing you’re looking at £523,000 for a bloke and

£586,000 for a woman.

So how do you save up that much? If your employer doesn’t offer a pension

scheme? Or the three million self-employed people? I did some work once with the

doyen of actuaries a man called Tom Ross, Past President of the Faculty of

Actuaries and we worked out a simple way of calculating what you should save up

for a pension. And let’s take someone on median earnings – that’s the middle of

the income range so if you stick a pin in the working population the one who

goes ouch is earning about £23,000. Suppose they start worrying about a pension

at 30, quite typical, and they want a modest half their income at 65. What do

they need to contribute each month from now on – guesses?

To have a good chance of a pension like that starting at 30 you would have to

save £5111 a year, £426 a month, almost a quarter of your pay. I did that

calculation for a book I wrote published by A&C Black Good grief! And at the

acblack.com website you can put in your own details and see what you should

save. And also your date of death.

Would any of you honestly go up to a person on £23,000 a year and expect them

to save not £20 a month, not £100 a month, not £250 a month but £426 a month?

It’s not going to happen. And that is why the government has introduced these

stupidly low amounts for the sort-of-compulsory pensions it is planning from

2012. They’re all it thinks people will pay. But it won’t buy them a decent

pension.

Pensions and risk

So what does all this tell us, tell you, about risk?

I would ask these questions

- Does it have a salary-related pension scheme?

- Is it a full final salary scheme?

- What has it done to mitigate the cost – later retirement, career average,

higher employee contributions

- Is it open or closed – if closed, to new members or existing

- If it is closed are there plans to ‘sell’ it – ie with negative money

- Is there a money purchase scheme – remember you can have both, especially

when salary related scheme has been closed.

- What are the contributions?

- If more than 3% before tax could they fall to that amount?

Now these things in a sense go both ways. A full blown final salary scheme

for all staff is a big cost, a big risk. But there are still all these measures

that can be taken to reduce that cost and risk.

On the other hand a company that has done all of this and is still in trouble

has nowhere to go.

I’ll only add one thing finally. Today’s fifty and sixty somethings are in a

golden age. Many of them had to join a company pension scheme and paid modest

amounts into a good final salary scheme and can retire at 60 – in jewellery. But

today’s thirty somethings are not going to have that chance – their pension

schemes are being cut back, closed, or they are so sceptical they are not

joining them because they don’t have to. And up to half of them may opt out even

of the Government’s new compulsion lite pension.

So that is another risk for the future. Companies that sell to the older

generation – Saga being the pre-eminent one – may be in their golden age too.

go back to Talks front page

go back to the Writing Archive front page

go back to the Paul Lewis front page

e-mail Paul Lewis

e-mail Paul Lewis

All material on these pages is © Paul Lewis 2006