This talk was given on 20 September 2005

The text here may not be identical to the spoken text

My title is, of course, the antithesis of the Financial Services Authority’s injunction to financial services companies that their advertising and promotional material should be ‘clear, fair and not misleading.’ And my thesis today is that the way that credit and associated products are sold is not fair, is misleading, and frequently is not clear either. Not that I am here to speak for the FSA – I have been a severe critic of the FSA in the past. But the principles it now lays down are useful and hard to disagree with.

It is just a coincidence that I had planned to talk to you among things about Payment Protection Insurance. A week ago Citizen’s Advice referred the question of PPI to the Office of Fair Trading. I’m not going to repeat the charges made there. Rather I am going to tell you what concerns me about PPI and how it reflects the problems the financial services industry has. The chief one of which is trust.

Over the last twenty years there have been at least five major financial scandals and many more minor ones. They mainly involved investment not borrowing. But none of these would have happened if the products had been explained clearly, fairly and in a way that was not misleading.

Take for example endowment mortgages. To buy our home we are sold

And to pay it off we were sold

And this will all happen when you are approaching retirement and have no way to earn extra money to repair the damage.

Explain it like that and no-one would have bought it. Around 12 million more people would have bought straight repayment mortgages. And today more than two million people would not be around £16 billion short of the money they need to repay their mortgage. Compensation? About £1 billion paid so far. And £8 million in fines on nine firms involved.

With all these major scandals – pensions, split capital investment trusts, AVCs, precipice bonds and in future maybe SERPS and venture capital trusts not to mention SIPPs – honesty and clarity in the product description would have stopped mis-selling. Of course it would also have led to far fewer sales.

At the heart of all this is commission.

In May I did a special programme on commission for Radio 4. We called it The Sins of Commission – you can hear it on our website, http://www.bbc.co.uk/moneybox and put ‘commission’ into the search box. One mortgage salesman in Cheshire told me he couldn’t make a living selling mortgages if he didn’t sell insurance too. His average mortgage was less than £100,000 and even one that big would only bring him £350. But if he added on life insurance, critical illness, and so on he could easily make £2,000. So was a mortgage a loss leader to get this other business? ‘Yes’ he told me. And I am sure you all know, as he did, unscrupulous advisers who sell all that and payment protection insurance rolled up in advance and added onto an expensive sub-prime loan, who can earn themselves - £4000.

People come for a loan. But they leave with insurance.

Treating customers fairly means minimising commission, not maximising it.

So why does the credit industry pay people so little for selling your loans that the only way they can make a living is to sell insurance?

The bias towards insurance is also on your websites. And very misleading stuff it is too.

For my example I am picking, rather than picking on, Barclays. It could have been any of them. But Barclays is first in the alphabet – apart from Abbey and that begins with S nowadays doesn’t it – and as someone who was with the Woolwich I am a small shareholder. The problems on the website start long before you get to the insurance. What is the key fact you need to know about a loan – the APR. So what does Barclays charge?

Here is its website.

6.7% APR typical.

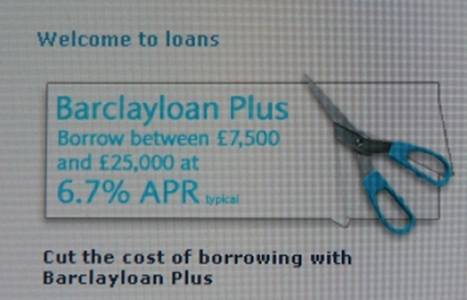

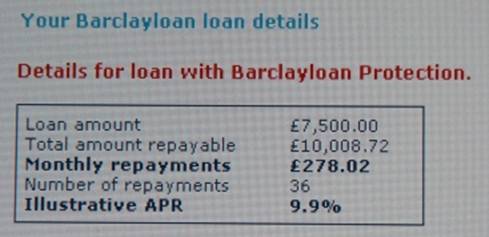

So I ask about £7500 over three years. And the answer is – 9.9% illustrative APR

.

Which is odd. Especially as I had a leaflet too.

which said 7.9% typical.

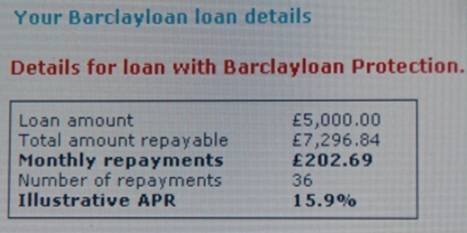

So I put in another figure. £5000 over 36 months.

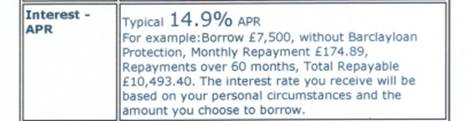

And I got another number, this time 15.9% illustrative APR. And when I clicked on the Summary Box to see what I was getting I got this.

typical 14.9% APR.

Now I know all about risk based pricing. Or relationship pricing as I’ve heard it called. Name a price, form a relationship, then double it. But just what is the price of a Barclays loan? It’s a bit of a lottery. So here they are again in numerical order - 6.9%, 7.9%, 9.9%, 14.9% or 15.9%?

Whatever else it is it’s not clear. And it is misleading.

When you ask for these quotes, opting in to the payment protection insurance is of course already checked, you have to tick ‘no’ to find the cost without optional Barclayloan Protection, as it is called. NatWest even calls this product ‘Loan Protector’!

Which is of course insurance. Because insurance has been rebranded ‘protection’. Marvellous products that protect us from all sorts of horrible things. Home contents protection? Does it prevent me getting burgled? No. ID Theft protection. Does it stop my ID being stolen? No. It’s not protection, is it? It’s insurance. A word we all understand. After 200 years why call it something else?

Especially as we will see the last thing it does for many people is protect their loan.

Here is how this insurance is described on the Barclays website.

“You must make repayments on your loan even if you suffer an accident, illness or unemployment. Barclayloan Protection can provide peace of mind.”

So you click on Barclayloan Protection to find out more.

Barclayloan Protection

Could

sickness, accident or unemployment happen to me?

The answer is 'yes'.

Look at the facts below and see how Barclayloan Protection could give you peace of mind.

Did you know that:

In 2000 there were 1.6 million people out of work. (Source: Office of National Statistics).

In 1999, 42,545 people were killed or seriously injured in road traffic accidents. (Source: Office of National Statistics).

Now I don’t want to seem picky. But there is no Office OF National Statistics. It used to be the Office FOR National Statistics not OF, but some time ago it was renamed National Statistics. And that would seem picky if the same standard of inaccuracy wasn’t followed right through.

The figures are out of date. Today 1.42 million are out of work (or more accurately actively seeking work). But they couldn’t claim. You have to get Jobseeker's Allowance to claim. And there 866,000 who claim that. But even that isn’t enough. You must also have lost your job though redundancy – there were 548,000 people made redundant in the last year. Not even all of them can claim as redundancy has to be compulsory not voluntary. Neither National Statsitics nor any of the work based research organisations know how the figure breaks down into compulsory and voluntary redundancy. But we do know without that that the number who could claim is at least a million less than the 1.6 million implies.

And the next statistic is no better. It implies that 42,545 people could have a claim. But the figure is out of date, by 2003 it had fallen to 37,215, includes children and pensioners who can’t claim leaving 26,521 and of those around a fifth will not be working so again cannot claim. Altogether only about 20,000 of these people could have a claim, less than half of that big headline number.

The figures are also irrelevant. You might look at them and ask ‘so what?’ Shit happens. What does this insurance actually do?’

But you don’t. Having looked at these out of date facts that are (a) not fair and (b) misleading you decide to proceed.

A box asks ‘Have you read the guide to insurance’ You think you just have and click ‘yes’. It allows you to proceed even if you haven’t clicked through to read the guide to insurance. Because those figures were not it. No the guide to insurance is this.

Can you read it? No? Well there are two more pages like this and if you print them out you need a magnifying glass to read it before you can even try to understand it. Well never mind it’s all lawyer’s gobbledegook. Just sign it.

Let me list for you what part of that gobbledegook really says.

We will not pay you on unemployment, if you

Not much protection of your Barclayloan there is there? And there are further restrictions on claiming after sickness or an accident. Now of course insurance has exclusions. It couldn’t work if it paid everyone. But shouldn’t they be shown clearly upfront?

Don’t take out this policy if you are self-employed. It will only pay you if you go bust. Don’t buy it if you are approaching 65 or intend to retire early. Or you went to the doctor for stomach ache or a cough in the last two years. Or you have had backache or depression in the last five years. And so on. Now that would be fair. After all you don’t want people to take out the policy who can’t claim do you?

Or do you?

I did the arithmetic. About 15% of claims are disallowed. So one in six or seven people sold PPI could not claim. Only around 4% tops actually put in a claim. So here is how that combines

The arithmetic says that complaints will be few enough to be treated like an overhead. So ‘Pile ’em high. Sell ’em dear’

Of course what Jack Cohen of Tesco actually said was ‘Pile ’em high. Sell ’em cheap’. But although insurance is piled high, it’s not cheap. What should it cost? Half as much as the interest? As much as the interest. Twice as much as the interest.

I first looked at this some years ago. And those figures show that as the cost of borrowing has come down, the cost of insurance has gone up. I think you’ve just been caught in cross-subsidisation. But today, on a standard £5000 loan over three years, the median extra cost of insurance more than doubles the cost of the loan. For every £100 of interest you pay £138 of insurance. And that is just £138 typical – if I can use such a phrase. Here is how it works out.

Goldfish is 42nd in a table of 84 loans available on the High Street listed in September’s MoneyFacts and ordered by the cost of insurance over the cost of the interest. It costs over the three years £558 to borrow that money. But with insurance it costs £1328 which is an extra £769. And the APR jumps from 7.2% to £17.2% - if you added it in – which you should – but you don’t.

|

GOLDFISH |

No Insurance |

With Insurance |

Extra |

|

Per month |

£154.41 |

£175.78 |

£21.37 |

|

Cost of loan |

£558.76 |

£1328.08 |

£769.32 |

|

APR |

7.2% |

17.2% |

10% |

|

COST |

Highest 1st |

median 42nd |

Lowest 84th |

|

Interest |

£1237.36 Barclayloan |

£561.28 Cumberland BS |

£432.76 Furness BS |

|

APR |

15.9% |

7.2% |

5.6% |

|

Insurance |

£1367.64 Bank of Scotland |

£914.40 Yorkshire Bank |

£495.36 Northern Rock |

|

Total cost |

£2517.16 Britannia BS |

£1534.36 Universal BS |

£931.36 Northern Rock |

|

Total ‘APR’ |

32.8% |

19.7% |

12.0% |

|

Ratio insurance/interest |

2.25:1 RAC Financial services |

1.38:1 Goldfish |

0.86:1 Barclayloan |

|

Insurance |

More than trebles |

More than doubles |

Nearly doubles |

So payment protection insurance is very expensive – more expensive than borrowing money in almost all cases – and may not perform as the customer believes it should – as the customer was led to believe it should.

Treating customers fairly – the sales side of the advertising slogan ‘clear, fair, and not misleading’ – means not selling them stuff which won’t fulfil its implied promises and which they don’t need.

Get your sales people to ask this simple question. If I wasn’t paid commission for selling this, would I sell it? If the answer is anything except ‘yes absolutely’ don’t sell it.

But there is more wrong with the credit business than unnecessary and expensive insurance.

Figures a couple of weeks ago from APACS the clearing system revealed that spending on plastic had finally overtaken cash. But using the word ‘plastic’ like that is itself misleading. Because as you all know plastic is not one way of spending money but two.

With a debit card the money comes out of your bank account, normally the next day. But with a credit card of course you borrow the money. So, debit cards are buying stuff by spending. Credit cards are buying stuff by borrowing.

Put simply

Debit card = spending

Credit card = borrowing

Now you know that. I know that. Many people don’t. And a caption like this in Post-It yellow on marketing material would go a long way to warn people. Because many people treat them the same. They buy things on their credit card which they wouldn’t dream of taking out a loan to buy. A third of our plastic spending is on a credit card. You put it behind the bar when you meet friends and then use it to buy groceries on the way home. You run out of cash and use your credit card to buy a DVD and a take-away for an evening in. Borrowing money over an indefinite period for stuff you no longer have.

The golden rule in my book – which incidentally is called Money Magic from all good booksellers – is never borrow to buy something which will be gone before the debt is paid. So if you pay for Christmas on your card, pay it off by next December. If you pay for a holiday, pay it off in six months before you are hankering for another. Pay off clothes in four months – you know you won’t wear them much after that. Different rules for men and women there obviously! And never borrow to go to a concert, eat out or buy a week’s groceries. You could be paying interest on them for years. How clear, fair and not misleading it would be to tell people that.

Instead, the monthly bill comes and you encourage them to pay as little as possible. Which you decide. They might owe £1000 and pay off £20. Leaving £980 but interest adds back £13. So they still owe £993. They have paid £20 and the debt has come down by £7. Do you tell them that? No. And that’s just at 14.9% - one of the lower rates, illustrative or typical, on the credit card market. And if you’ve also sold them PPI they may never pay it off.

So it’s no surprise that personal debt in the UK is now well over a trillion pounds. In fact at the end of July 2005 it was rather more than that £1,113,600,000,000. Most of that sum is home loans so if we take out mortgages we actually owe a shade under £190 billion on credit cards, overdrafts, personal loans, hire purchase and so on. In fact £189,800,000,000. Given that just over half the population does not owe anything, the 21 million adults in the UK who do, owe more than £9038 each.

Now some will tell you that figure should be less. The Bank of England Quarterly Bulletin Winter 2004 gives £4860. But you can combine the figures in it with other Bank of England figures to get £15,379. I will stick with my calculation which is somewhere in the middle. What we do know is that when it comes to problem debt, people who work in debt counselling agencies say that debts of £100,000 are no longer that uncommon. And we do know that credit cards are the biggest single source of that debt.

And the way that the industry fixes the terms makes it happen. Take that minimum repayment. The example I gave there was LloydsTSB but it could be most of you. Out of 64 credit card providers listed in MoneyFacts 26 have a minimum repayment of 2%. Now that means the debt will take 19 years and 9 months to pay off and earn you £1154 in interest. More than was borrowed. And this is at 14.9%, not extreme in the credit card market. Another 12, heeding calls to raise the minimum, have one of 2.25%. That doesn’t help much. Just five have a repayment of 5% which dramatically reduces the time to pay off and the interest paid. Nearly 7 years instead of nearly 20 and less than £300 instead of nearly £1200. The rest are almost all 3%. None has 10%. Which really would cut the cost. I wonder why?

|

Min |

No. |

£1000 at 14.9% debt paid off |

|

|

2% |

26 |

19 years 9 months |

£1154.45 |

|

2.25% |

12 |

16 years 6 months |

£916.10 |

|

2.5% |

1 |

14 years 4 months |

£761.35 |

|

3% |

19 |

11 years 6 months |

£571.23 |

|

4% |

1 |

8 years 5 months |

£383.25 |

|

5% |

5 |

6 years 9 months |

£289.44 |

|

10% |

0 |

3 years 7 months |

£132.36 |

|

2% fixed |

0 |

5 years 0 months |

£413.47 |

And why is the repayment fixed in this way anyway? x% or £5 whichever is the less. Someone with that £1000 debt at 14,9% has to repay around £20 a month at first. If they can afford it then, they can carry on affording it. Suppose it was fixed at the same rate as the first payment. They would pay off the debt in 5 years and pay £413 in interest.

I mentioned earlier the trillion pound debt. The near £190 billion unsecured loans. The average £9038 each for those in debt.

I wonder how many of you feel any responsibility for that figure? Is it

You tell me.

Let’s assume that easy credit is a good thing.

But of course the whole system of instant credit decisions only works because of organisations like Callcredit, Experian and Equifax. It works well. But it is not infallible. Let’s say it is right 90% of the time. And let’s say the failures fall equally in two. One in 20 doesn’t get credit who should. Lost customers. Angry customers very often. ‘I’ve been a customer for thirty years and I have never been so insulted etc.’ Writes embarrassed in front of other shoppers from Tunbridge Wells.

But one in 20 has the opposite problem. They get credit and shouldn’t. Now they only have that problem because the systems that help all the rest of us work less than perfectly. So wouldn’t it be fair for the lending industry to use some of the money made from the rest of us to help the people whom the system fails? And I don’t mean the odd fiver to one of the debt helplines. I mean serious money. Eight figures money. And linked to the number of bad debts. Tens of millions. Out of profits of billions.

And it would be in your interest as well as your customers’ to cut the number of people needing help. And that means changing your ways. Getting rid of

That would turn unclear, unfair and misleading into clear, fair and not misleading.

Surely that is a goal worth aiming for. And surely that would help restore the trust the financial services industry so desperately needs.

20 September 2005